Of the dozen fashion exhibitions Diana Vreeland produced at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1973 to 1987, “The Glory of Russian Costume”—with its “rich peasants,” real peasants, aristocrats, and monarchs—was her chef d’oeuvre, culling her biggest “gets.” But according to Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel, a documentary opening this month, in some ways the doyenne’s celebration of Russian robes and raiments was just like her other Met shows: a platform for romance and personal fantasy. Vreeland, who died in 1989 at 86, was no more interested in chronology and historical accuracy than in the pickings at Macy’s.

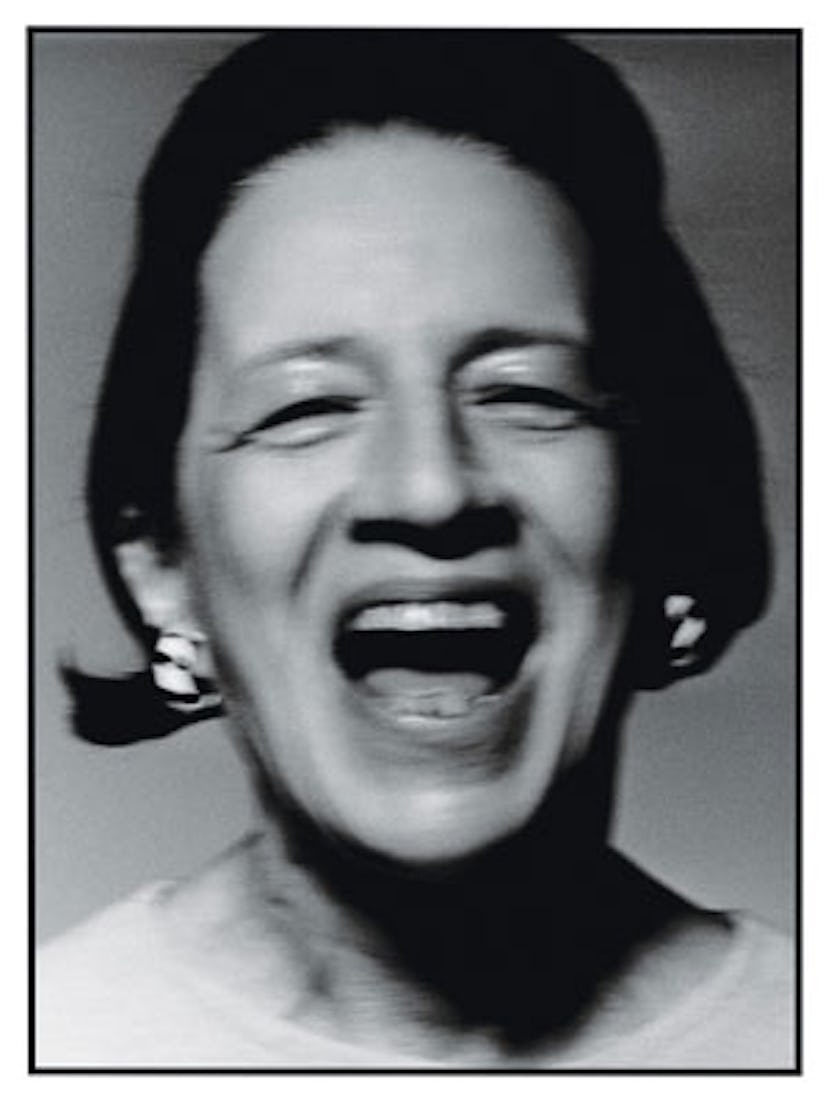

The film, by Lisa Immordino Vreeland, who is married to her subject’s grandson Alexander, captures the brisk sculptural gestures, opaque rhetorical outpourings, and deliciously associative mind (ordering gigot in a restaurant could lead in a hair’s breadth to a monologue on gigolos) of a colossally stylish but homely woman with what can only be described as a turnip nose. Vreeland was the fashion editor at Harper’s Bazaar for just more than a quarter of a century, a period in which she said she received a single raise, her salary never topping $19,000. Immediately following Bazaar, for eight years starting in 1963, she was the editor in chief of Vogue. On her watch, Vreeland once famously proclaimed that Vogue was “the myth of the next reality.”

Immordino drew her narrative from some 35 hours of taped conversations George Plimpton had with Vreeland while working on her “faction”-filled memoir, D.V., published in 1984. (Plimpton’s widow, Sarah, has yet more tapes.) Immordino found a full set of bound Bazaars from Vreeland’s years at Hearst right where she carelessly left them in 1962: in the attic of the house in Brewster, New York, she had sold that year. There is wonderful footage from Bruce Weber’s Chop Suey of her lair at 550 Park Avenue—with its Christian Bérard portraits of “Dee-AHN-a,” army of blackamoors, and Billy Baldwin–selected “garden in hell” chintz. Immordino never gave up searching for a Dick Cavett Show featuring Vreeland, even after Cavett confirmed that his secretary had lost or erased a number of segments. It surfaced at the 11th hour in the Library of Congress.

When patchworking this material, Immordino says, the goal of her team (which included codirectors/editors Bent-Jorgen Perlmutt and Frédéric Tcheng, who collaborated on Valentino: The Last Emperor) was to re-create the jumpy editorial rhythm of Vreeland’s Vogue. Hence the aural motif of castanets clacking away as Immordino unravels the queer home-baked logic Vreeland used to slay doubters, amusing them even while annoying them. A pair of shoes might have been historically correct for a certain dress in one of her Met exhibitions—but wrong if she found them less than ravishing. The woman whom the mannequin stood in for would have rejected the “right” shoes, Vreeland parried when challenged by curatorial wonks, and worn the more beautiful ones. Never mind that since the shoes postdated the dress by 30 years, the woman could hardly have known them. Pressed further, Vreeland, teetering on exasperation, insisted: “Well, she would have thought of them.”

“She always claimed that her idea for ‘The Great Fur Caravan’ shoot Avedon did for Vogue in Japan with Veruschka and a sumo wrestler was inspired by The Tale of Genji,” Immordino says. “She never even read it!”

While elegantly balanced, The Eye Has to Travel is not unsparing, skirting as it does any mention of the mistresses (Edwina Mountbatten was always rumored to have been one) of Vreeland’s conspicuously good-looking husband, Reed, a banker who was later employed by the Rigaud candle company. But it does address her discomfort with emotion and shortcomings as a materfamilias. Immordino rightly judged that the credibility of her film depended on getting Immordino’s father-in-law, Frecky, and his brother, Tim, to open up about their mother’s indifference-slash-neglect.

“There’s a reason they left New York,” says the willowy and fresh-faced 48-year-old director, whose interest in artifice, it turns out, is purely professional. Immordino is almost disarmingly natural and direct—what Vreeland would have called sans façon. “Both sons were absent during some of the most difficult moments in her life”—Frecky as U.S. ambassador to Morocco and Tim as the dean of architecture at UCLA. “And she clearly was not with them during theirs. But listen, kids have been treated worse.”

Kids, if not assistants. Ali MacGraw makes the point that The Devil Wears Prada’s Miranda Priestly was not the first fashion magazine chieftess to bark orders or throw her coat at an underling. Unlike the fictional Andrea Sachs, however, MacGraw, straight out of Wellesley and on the receiving end of Vreeland’s manteau and commands (“Girl, get me some pencils!”; “I need Cecil Beaton!”), didn’t take it. In the film, the actress says she “chucked” her boss’s coat right back.

Immordino never knew Vreeland, a fact she thinks made keeping her distance easier. Still, she says, “Her life had this texture nobody else’s had, and she herself this openness, and you do become a little changed by it. She was interested in everyone—the security guards at the museum, a favorite cab driver she used to invite to dinner. But I’m not sure she would have liked me. I’m not sure I was her kind of girl.”