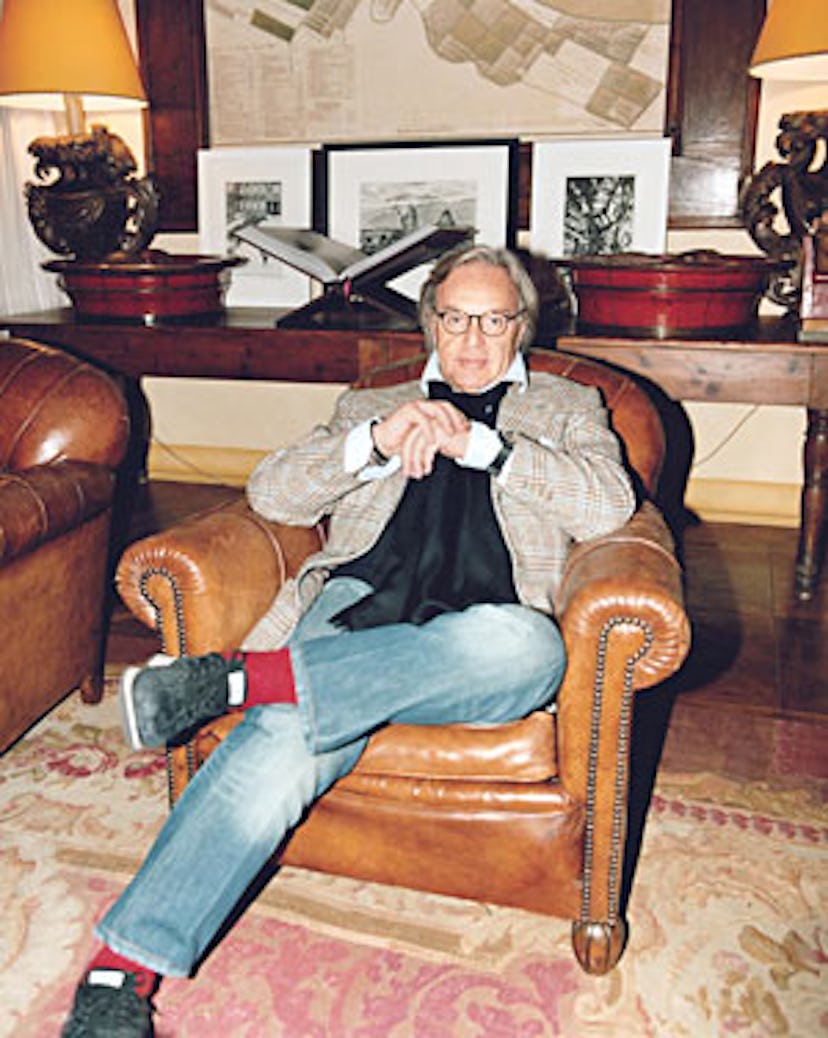

Diego Della Valle can’t stop touching people. The Italian entrepreneur works the room, greeting friends and local dignitaries. “Benvenuto,” he says, offering a smile, a handshake and a squeeze of the arm just above the elbow to each and every guest. Of average height and build, with a full head of graying hair and round glasses that make him look like Harry Potter’s older alter ego, Della Valle, 55, is one of Italy’s most powerful industrialists. On this brisk November evening in Florence, his role is that of honorary chairman of the Renaissance city’s soccer club ACF Fiorentina, which he rescued from bankruptcy in 2002. “I always come to the stadium knowing it’s a game. If we win, I sleep better,” he says in the executive lounge of Fiorentina’s Stadio Artemio Franchi. His voice is rusty and lulling.

The soccer club is but one of many commercial endeavors through which Della Valle has become a pillar of Italian capitalism, amassing a fortune estimated at close to a billion dollars. He has holdings in RCS Media Group, which owns the Corriere della Sera newspaper; Banca Nazionale del Lavoro; furniture firm Poltrona Frau; film studio Cinecittà; eyewear company Marcolin; and Piaggio motorcycles. He is also working on a project with Ferrari president and longtime friend Luca Cordero di Montezemolo to launch a high-speed train company. Dubbed NTV, the service is slated to compete with a state-run network starting in 2011. But it all started with his family’s leather business, which he developed into the luxury conglomerate Tod’s SpA.

The morning after the game, Della Valle’s pilot, Franco Macchi, readies his silver Falcon 2000 10- seat private jet for the short flight back to Milan. Like many who work for Signor Diego, the pilot has been doing so for more than a decade. A half dozen pens, a notepad and stacks of papers in tan folders fastened with a single blue and yellow striped ribbon await Della Valle, tokens of the busy day ahead. Twenty minutes later he boards, accompanied by an entourage of three: a bodyguard, Della Valle’s brother and a cousin. Last night’s jacket and jeans have been swapped for a navy suit and tie. “Sorry I’m late,” Della Valle says, adjusting the leather bangles on his right wrist as he relaxes into his seat.

Behind Della Valle, on the wall of the cabin, a plaque bears the letters d.d.d., which stand for dignita, dovere, e divertimento, or “dignity, duty and fun,” a phrase he coined. “It’s the synthesis of what’s important in life,” Della Valle says as he fastens his seat belt. “As a family joke, we made it into a coat of arms in blue and yellow, which are my favorite colors. We all have one in our homes and on our boats as a reminder of what it means to be a Della Valle.”

From top: A python bag; an alligator bag.

The engines start up, and the conversation turns briefly to soccer, until Della Valle notices his publicist’s bag on the floor in front of him. “It’s beautiful,” he says, proudly caressing the off-white rounded calfskin D-Bag from Tod’s fall 2008 collection. As the head of a publicly traded, billion-dollar luxury empire—which also includes the Hogan, Roger Vivier and Fay brands and employs nearly 3,000 people— Della Valle is entitled to a bit of pride, particularly in view of his humble beginnings.

Della Valle was born and raised in Sant’Elpidio a Mare, a small town in the Marche region, a hub of shoemaking located a third of the way down the east coast of Italy’s boot-shaped peninsula. His grandfather was a cobbler, and his father, Dorino Della Valle, built a business making shoes for Azzedine Alaïa, Calvin Klein and Neiman Marcus, among others. Not wanting his children to follow him into the trade, Dorino sent his eldest son to a university in Bologna to study law. It didn’t work.

“I was a bit undisciplined,” Della Valle confesses. “Where there was a bit of fantasy, I did well. But when it came to studying math…. Well, anyway, I always wanted to have this profession. I was always hanging around the factory as a boy. I just liked being there. Even today when I go into the materials warehouse, which is the size of a soccer pitch, I’m like a kid in a candy shop.”

Della Valle’s early “mania” for shoes, as he describes it, led him to entrepreneurial ends. One afternoon he skipped school and took the train to visit the biggest supplier of molded plastic shoe forms in Europe, which happened to be in Le Marche. Despite being only 15 and arriving without an appointment, he asked the supplier to make a prototype of a shoe he’d designed. The supplier, who knew Dorino, was amused by the precocious teenager and conceded.

“He is single-minded and very determined,” says Della Valle’s brother Andrea, 43, vice chairman and managing director of Tod’s SpA and chairman of Fiorentina. “When Diego has a clear and precise idea of what he wants, he sees it through to the end.”

Diego may have closed his first deal with the plastic shoe-form supplier, but Dorino took more convincing. After his son spent many years sampling university life, mostly outside the classroom—at bars, playing billiards, chasing girls—the casinista, or rascal, as Diego describes his younger self, dropped out to join the family trade.

“I could have killed him,” recalls Della Valle senior a week later during his daily rounds at the firm’s shoe factory in Cassette d’Ete. Known affectionately as Signor Doro (which in Italian means “Mr. Gold”), Dorino shares his son’s passion. At 83, he often rides a bicycle around the sprawling plant to check on production, offering advice along the way. Like his son, he has an inimitable, though very different, sense of style, punctuated by a snowy mustache. Today, in a gray cashmere tracksuit, self-designed white leather shoes, and sunglasses and carrying a silver-handled black cane, he looks like a pimped-out Clark Gable. “The factory was supposed to stop with me,” he says. “But it was impossible to stop Diego.”

Dorino’s maverick son joined the family business in 1975 and renamed it J.P. Tod’s a few years later, picking the name out of a Boston phone book because it was short and easy to pronounce internationally. (He eventually dropped the initials.) Tod’s first success came with the Gommino driving shoe, which, as the name suggests, has gummy little rubber pebbles on the soles. It put the label on the map. “Almost everyone wears rubber on their feet these days, but there was a time when it was considered cheap. Luxury shoes had leather soles, which were rigid and heavy. We turned that concept on its head,” says Della Valle. Shoes led to bags in 1997 with the D-Bag, which created buzz from Hawaii to the Hamptons. Ready-to-wear came along in 2006, quickly establishing a celebrity following that includes Katie Holmes and Jessica Alba. And for those who like their heels haute, the firm just introduced a separate high-end line of footwear and accessories for the spring 2009 ready-to-wear season in Milan. Tod’s sunglasses are set to debut in September.

Tod’s creative director, Derek Lam, who oversees ready-to-wear as well as accessories, describes Della Valle as warm and decisive, and says his strength lies in having a very clear idea of what he wants: lasting luxury products that work in a fashionable person’s wardrobe. “If he loves it, he loves it,” says Lam. “He doesn’t micromanage.”

Della Valle says the key to Tod’s strength lies in manufacturing 100 percent of its products made in Italy and relying on skilled artisans who create practical things in the most beautiful way possible. His headquarters in Cassette d’Ete is testament to this. Surrounded by lush green lawns and olive trees and with an Italian flag out front, it was designed in 1997 by Della Valle’s third and current wife, Barbara, who is an architect. (She is also the sister of his first wife, whom he divorced and with whom he has a son, Emanuele, 33.) The white stone and glass facade resembles a museum of modern art more than it does a factory, a feeling that extends inside, where floor-to-ceiling photos of a footprint in yellow and a studded Gommino sole in blue stand sentry at both sides of the atrium. Ahead, the shell of a Ferrari Formula One racing car—a gift from Montezemolo—is parked at the crossroads of four long, naturally lit corridors. Farther in, two Jacob Hashimoto kite installations flutter overhead, while Ron Arad’s specially commissioned stainless steel staircase links the first and second floors. There are also monuments to Della Valle’s family history, such as his grandfather’s tooling desk, which sits outside the prototyping room.

Opening the doors to each discrete zone is like lifting the lid of a well-oiled machine. In the styling offices, Lam’s teams of designers dream up the next collections; in the prototyping room men and women in white coats make the shoe lasts and draft patterns; and in production, scores of workers cut the leather and construct the shoes. The site whirs with the quiet sound of hard work. Though the factory produces two million pairs of shoes per year, there is a handmade element to each phase of the manufacturing process.

Della Valle likes to visit the factory whenever he can to check that the essence of each label is being respected in terms of quality, aesthetic and concept. (While Hogan is known for sportier shoes and accessories and Fay for casual wear, Roger Vivier, which Della Valle acquired in 2000, has been described as the “Fabergé of footwear,” with prices to match.) He also enjoys chatting with some of the older employees there. The average age of a Tod’s leather worker is 35, but in some cases two or three generations of the same family work at the factory. “They are my wealth,” he says. “Thanks to thousands of people, we can speak of a product that is unparalleled.”

The feeling is apparently mutual, with many of the staffers boasting that they work for Signor Diego. They have good reason to, given how high quality of life ranks at the company. The facility in Cassette d’Ete features an auditorium, a gym, an infirmary, a restaurant and a kindergarten, free for the children of all employees—including Della Valle’s. His youngest son, Filippo, now 11, attended the school; Andrea’s three-year-old daughter, Margherita, is one of the 28 kids singing nursery rhymes there this morning.

While he may have an eye for high-quality leather goods, what gives Della Valle an edge over his peers is his marketing savvy. He often talks of selling a dream of exclusivity and throughout his career has associated himself with iconic figures, such as Gianni Agnelli, the late Italian industrialist and owner of automobile company Fiat SpA, and John F. Kennedy. When he started out, Della Valle sent a pair of Gommini to Agnelli, who sparked a trend when he wore them. In 2005 Della Valle bought JFK’s mahogany Marlin yacht, which is moored at his holiday home in Capri; a painting of the president hangs in his office. His admiration of both men speaks to a desire to be like them: good-looking, wealthy, well respected and a bit of a rake. By all accounts, he’s succeeded on each of these fronts.

Della Valle’s latest muse is Gwyneth Paltrow. He picked her as the face of the brand not only because she represents his ideal Tod’s woman but also because she is, as most Italian guys like their gals, a brava mamma, or a good mother. And she cooks. “She’s a normal person for part of her life and an idol for another,” he says. “It’s always an important ingredient when there is a serious product and a famous, clean-living face.”

Back at the factory, Della Valle is dressed in jeans, a navy blue cashmere blazer, a light blue shirt—the upturned collar of which peeks out from under a black scarf, his signature look—and a pair of cream-colored Hogan sneakers. A green and red pin glistens on his lapel.

“Unfortunately this is for when you’ve had electric shock treatment at school,” he says, thumbing the pin. “You have to wear it to show that you are not allowed to drive a car or have more than three coffees a day.” An impish grin stretches across his face. The pin is actually the Cavalieri del Lavoro, Italy’s highest honor for services to industry. Della Valle received it in 1996. “We’re a bit like soldiers of the workplace,” he quips of his co-cavalieri.

He’s not kidding. Della Valle’s life is organized with military precision. Every other month he takes a long-distance trip, typically to the U.S. or the Far East. In between he travels around Europe, working 12- to 15-hour days. In total he spends about 400 hours a year on his plane, enough for about 10 laps around the world.

Whenever possible, however, Della Valle spends Friday night through Tuesday at home, in the area where he was born. In the morning he brings Filippo to school, the same one he attended; he eats lunch at home, a former convent surrounded by acres of private parkland that is a short drive from the factory; and he visits the grave of his beloved mother, who died last October. “That is the world in which I feel most comfortable,” Della Valle says. “I prefer a simple, normal life. I avoid the beau monde unless for work.”

According to Montezemolo, he’s always been like that. “Diego is one of those people that we in Italy call a ragazzo del bar, those guys that you see with four or five friends who like to joke around, eat well and hang out in familiar haunts,” Montezemolo says. “He is very attached to where he comes from and his family. These values are important, and despite his success, he has never lost them.”

Over a lunch of ricotta and spinach ravioli, veal, salad, fruit and chestnuts—the majority of which comes from his estate—Della Valle introduces Filippo, his son by Barbara. Filippo, a good-looking boy with chocolate brown hair and eyes, starts a conversation about the latest Bond film, Quantum of Solace. He has his father’s full attention. “It’s really good. There’s loads of shooting,” Filippo says, getting out of his chair to approach Diego.

“And good-looking women?” Della Valle asks, grabbing his son around the rib cage. In Italy, Della Valle is known as much as a ladies’ man as a guys’ guy. But at home he’s just Dad. “Actions speak louder than words,” he says. “Image is something you construct, while reputation starts at home. If you are able to pass on solid values to your children, then they can become citizens of the world.”