Black Power Dressing

In the ’60s and ’70s, Ebony magazine founder Eunice Johnson changed the color of fashion. A new exhibition pays tribute.

For nearly half a century, starting in the late ’50s, a Greyhound bus full of African-American models spent four months each year touring the United States, its cargo hold stuffed with hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of designer clothes. Each day, the bus stopped in a new city—from Hamden, Connecticut, to Itta Bena, Mississippi—and the models, accompanied by a jazz band that traveled with them, put on an elaborate fashion show for a largely African-American audience, strutting the catwalk in the most avant-garde gowns that designers like Yves Saint Laurent, Emanuel Ungaro, and Christian Lacroix had to offer. This was the Ebony Fashion Fair, and its founder, the late Eunice Walker Johnson, did perhaps more than anyone else to break down fashion’s color barrier.

“The fair was about using fashion to put forth new ideas about black life and who African-Americans could be and were aspiring to be,” says Joy Bivins, cocurator with Virginia Heaven, of “Inspiring Beauty: 50 Years of Ebony Fashion Fair,” which opens this month at the Chicago History Museum and runs through January 5, 2014. The exhibition delves into the fair’s vast archive, which includes key pieces in the history of modern fashion like an evening ensemble from Saint Laurent’s famous 1977 Chinoiserie collection, a 1968 iridescent pink jumpsuit and purple faux-fur coat by Christian Dior, and a Christian Lacroix–designed Jean Patou evening dress from 1986. “Bringing those garments to a black audience and putting them on black models said not only ‘You can wear these things’ but also ‘You are the standard of beauty,’ ” Bivins says. “It was a revolutionary act.”

Fashion revolutionary was not an obvious career choice for Johnson. The daughter of a surgeon and a schoolteacher, she was born Eunice in Selma, Alabama, in 1916, and graduated from Talladega College with a degree in sociology. While studying for a master’s in social work from Loyola University in Chicago, she met John H. Johnson, the editor of Supreme Liberty Life Insurance Company’s internal magazine, who had been raised by a single mother. According to Audrey Smaltz, the head coordinator of and commentator for the fair from 1970 until 1977, Eunice was betrothed to a well-known Atlanta physician at the time. “She liked to joke that she was engaged to a doctor and then she married a man who didn’t finish college,” Smaltz says. It was a smart move: Johnson, the founder of Johnson Publishing Company—owner of Jet and Ebony magazines—would go on to become the first African-American to make the Forbes 400, Forbes magazine’s list of the 400 wealthiest Americans.

Johnson Publishing got its start in 1942, a year after the couple married, when John, using his mother’s furniture as collateral, took out a $500 loan to start Negro Digest, an African-American take on Reader’s Digest. By 1943, the publication’s circulation had reached 50,000, and buoyed by its success, John came up with the concept for an African-American-focused magazine modeled on Life. It was Eunice, the company’s secretary-treasurer, who suggested calling it Ebony. The first issue appeared in 1945 and sold out on the newsstand. In 1951, the company launched the newsweekly Jet.

In addition to celebrity and news features, Ebony ran Fashion Fair, a section showcasing the best styles of the season on African-American models. It was a radical act at a time when segregation was still the norm and black women were very much excluded from the realm of high fashion. “The first time I saw women who looked like me be so fashionable was in the pages of Ebony,” says Desirée Rogers, former White House social secretary, who is now Johnson Publishing’s CEO.

Fashion Fair made the transition from the magazine to the catwalk in 1958, when Ebony was asked to produce a runway show to benefit a New Orleans hospital. The event was such a success that it traveled to 10 cities that year. Johnson Publishing paid for the venues and local African-American charities—churches, sororities, chapters of the Urban League—were responsible for selling tickets. The company deducted the cost of a subscription to Jet or Ebony from each ticket sale, and the rest went back to the nonprofits, ultimately raising $55 million for numerous charities over the years.

As time passed, Johnson upped the ante, adding live music, hand-painted sets, and more stops, visiting up to 170 cities a year. She was determined to introduce African-Americans to the very best from the European runways as well as to the work of America’s top designers. It was no small feat: The Civil Rights Movement was in full force, and many designers weren’t thrilled with the idea of seeing their clothes on black models. Johnson, however, was up for the challenge. “I would describe my mother as a steel magnolia,” says Linda Johnson Rice, now the chair of Johnson Publishing. “She was very intelligent, very persuasive.” And, says Johnson Rice, it helped that her mother, a meticulous woman known to color-coordinate her emerald and ruby rings with her Bill Blass and Dior day suits, “looked the part.”

Still, Johnson’s cold calls to European designers asking for invitations to their shows were not always well received. “Valentino once told us we couldn’t come to his show,” Smaltz claims. But others embraced the opportunity: Emilio Pucci, according to Johnson Rice, was one of the first, even asking Johnson if she could help find black models for his shows. “If you look at some of the photographs from the ’60s and ’70s, you see that Eunice is alone in a sea of white buyers,” Bivins says.

Johnson held a powerful trump card: cash. A lot of it. Unlike the heads of other charity fashion shows, she was looking to buy, not borrow, purchasing up to 200 looks a season. “We had stacks of checks, and we didn’t care about the balance—Mr. Johnson covered everything,” remembers Smaltz, who accompanied Johnson on buying trips and rode the bus with the models for months on end, creating a home away from home in the front seat, complete with carpeting, a lamp, and fresh flowers.

And Johnson was an incredibly enlightened consumer, one more interested in a designer’s creative vision than the commercial concerns that limit department store buyers and magazine editors. “She always homed in on the point of view of a collection and selected pieces that would tell that story,” says B. Michael, an African-American designer who was a Fashion Fair fixture. Christian Lacroix ranks Johnson among the people who best understood his work. “She was buying the most difficult, eccentric, and flamboyant numbers, often my favorites,” he says. “She wanted pieces that helped women feel unmissable, as if by wearing these clothes they were sharing the creative process with the designer.”

Still, each garment Johnson purchased did meet certain criteria: It had to look as good going down the runway as it did coming back. And she loved the idea of a big reveal; she’d often commission a wrap to accompany a strapless evening gown so the model could slowly show off the dress as she walked. Such theatricality was central to the Fashion Fair vibe, from the casting of the models to the style of the production. “You had to work it,” says Audrey Adams, who modeled in the 1975 season. “Be fabulous. And if you weren’t fabulous, [Johnson] would take that outfit away and give it to somebody who could carry it.”

The models, mostly unknown girls who ranged in age from late teens to early 20s, were specifically cast for their strength and presence. And as demanding as she could be, Johnson was highly protective of them. Beverly Johnson (no relation) recalls running into her in the ’70s. The supermodel, who by then had already been on the covers of both Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, offered to walk in the fair for free in New York and Buffalo. “Johnson responded, ‘And take the clothes away from the other girls? You have to do 88 cities and ride on the bus with all the others. Otherwise you can’t do it,’” Beverly recalls. “I was standing there with my mouth open. Now I realize she was really sticking up for her models—that’s the respect she had for them.”

And it was respect well earned. In the earlier days, the models encountered an even more violent strain of the racism that Johnson faced on buying trips. Pat Cleveland, who was 14 when she did the fair in 1965, recalls some “hairy” times in the Deep South. “There was a riot outside our hotel. People were walking around with torches and saying, ‘We don’t want niggers staying in the center of town.’ It was horrible. There were times when we had to leave town quickly because we were being harassed by the Ku Klux Klan. Our bus driver was a retired Marine, and he had a pistol and a rifle.”

But the shows, by everyone’s recollection, were utter magic. Akin to Broadway spectacles in choreography and entertainment value, they were two-hour stage pieces, complete with an intermission. “The models literally danced down the aisles, strutted and flung and turned, taking off a coat and doing a 360-degree turn and then snapping it over their shoulders,” says Rogers, who attended her first show when she was a teenager in New Orleans. “You could just hear the crowd go, ‘Ahhh.’ ” Says Cleveland: “It was like the Harlem Globetrotters meets Cirque du Soleil.”

While the fair was gaining a reputation as “a place to be,” as Rogers puts it, Johnson leveraged its success to delve further into the universe of style. When she realized her models were having problems finding makeup to match their skin tones, she created the Fashion Fair cosmetics line in 1973. It was wildly successful—Aretha Franklin appeared in the ads—and other companies like Revlon and Avon soon followed suit. Johnson also made special efforts to include African-American designers in her shows, providing less widely known names with a hit of fabulousness-by-association. “You were on the runway with Yves Saint Laurent or Oscar de la Renta, so I think from the perspective of the audience, it put you in the right frame,” B. Michael says.

As the Ebony Fashion Fair was becoming increasingly luxe and fabulous, so, too, was Johnson’s life. She and her husband had a house in Palm Springs, just down the street from Bob Hope’s, and in their apartment on Chicago’s Lakeshore Drive were works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Giorgio de Chirico. Perhaps her grandest design statement was Johnson Publishing’s headquarters, which she decorated with the interior designers Arthur Elrod and William Raiser. John Johnson loved red, so his office had a crimson alligator desk with a matching typewriter. Eunice’s office was a sea of ivory, with a sofa anchored to the wall to give the impression that it was floating. Liza Minnelli, Elton John, John Lennon, and the Jackson family all were treated to elaborate seated lunches and dinners in the orange, yellow, and purple cafeteria, which served up soul food, per John’s preference. Johnson often wore ensembles from her sizable couture collection and, as a major presence on the Chicago social circuit, also loved to show off her Ungaros and Lacroix at the opera or the Art Institute. For a dinner at the White House during the Reagan administration, she chose a red Dior gown shot through with gold Lurex. “She was never afraid of glamour in any shape or form,” Johnson Rice says.

That vision of glamour was quite literally the life force behind the Fashion Fair. When Johnson passed away in 2010 at 93, after having helmed the fair through 2009, the shows passed with her. But now, after a four-year hiatus, Rogers and Johnson Rice have decided to reignite the flame. In the fall, they will debut a new Ebony Fashion Fair, starting with just one or two cities and featuring a mix of archival pieces and contemporary looks. “The goal is, again, a celebration of fashion, of people coming together,” says Rogers, who will also relaunch the fair’s makeup line. “We are the curators of African-American fashion history, and we’re going to continue in that vein.”

Black Power Dressing

Model Audrey Adams on the runway at the Ebony Fashion Fair, 1976.

Eunice Johnson with Christian Dior designer Marc Bohan, 1976.

With Karl Lagerfeld, 1975.

The 1973 Ebony Fashion Fair poster.

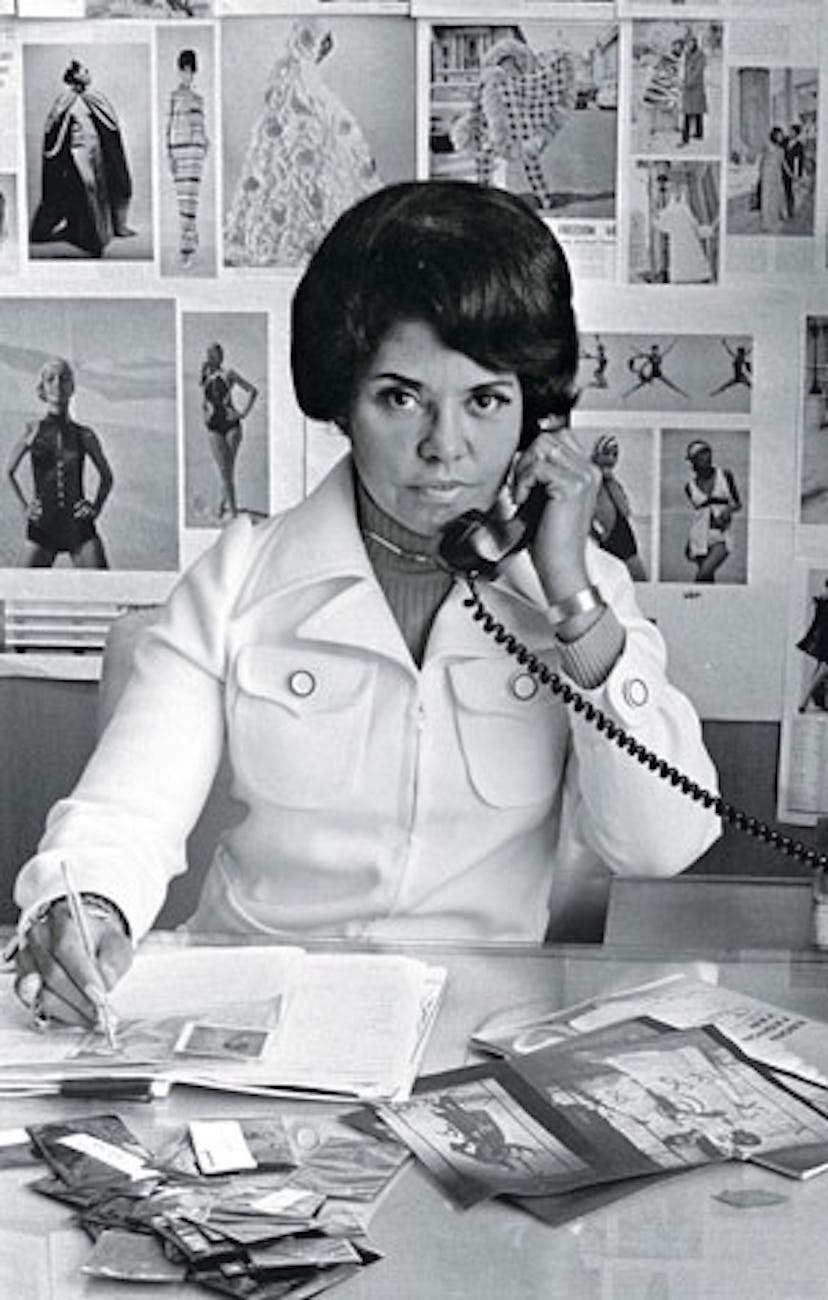

Johnson in her office at Johnson Publishing Company, 1970.

With Yves Saint Laurent, circa 2000.

Ebony Fashion Fair, 1975.

Johnson and her husband, John (third to her left), at the White House, celebrating the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, 1963.

With Pat Cleveland, 1972.

A reception area at the Johnson Publishing Company, 1972.

A 2007 look by Issey Miyake, part of the exhibit at the Chicago History Museum.

Jackie Robinson, Eunice Johnson, Jim Brown, Sammy Davis Jr., and John H. Johnson (from left) at Ebony’s 20th-anniversary luncheon at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, 1965.

At the Pauline Trigère show, 1971.

The Johnsons’ Chicago apartment, designed by Arthur Elrod and William Raiser, featured in Architectural Digest, 1972.

Looks from Givenchy by Alexander McQueen Haute Couture, 1997.