Can I Borrow That?

When designer “inspiration” jumps the fence to full-on derivation, the critics’ claws pop out.

We’ve all heard the fashion knockoff tales. On one hand, there’s the down-market riffing on designer motifs that ranges from the H&Ms and Forever 21s of the world to counterfeit duds channeled through Chinatown dens. But pilfering exists at all levels of fashion, including at the very pinnacle. And up in the stratosphere, it becomes increasingly difficult to categorize, to draw the line between legitimate inspiration and flat-out derivation.

Not a season goes by when fashion critics don’t home in on references within certain collections. Consider the recent spring 2008 Proenza Schouler effort. Designers Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez received accolades for their precise rendering of a military motif—trim, brass-buttoned vests, slickly tailored striped jackets and to-die-for feathery numbers seemingly dipped in gold. But the praise was more than tempered by an observation repeated by critic after critic: Too close for comfort to the work of Balenciaga’s Nicolas Ghesquière, noted The New York Times, The International Herald Tribune and Women’s Wear Daily, W’s sister publication.

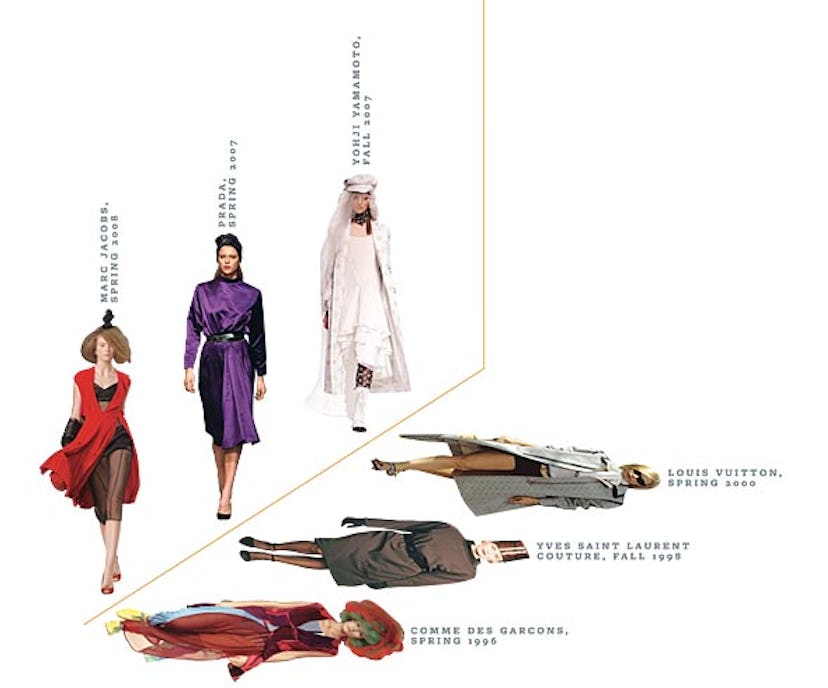

The Proenza Schouler boys certainly weren’t alone. WWD called Brian Reyes’s leg-baring tunics a “big Prada-esque question mark” and slammed MaxMara for dumbing down Yohji Yamamoto. Style.com noted that Alessandro Dell’Acqua “didn’t touch on anything Prada and Dolce & Gabbana (or even Helmut Lang…) didn’t do 10 or so years ago.” Christopher Kane’s collection, according to the Times, brought to mind “the late Nineties of Daryl Kerrigan.”

Those designers all garnered negative critiques for their apparent cribbing—and justly so, right? After all, as every schoolkid who’s ever sat through a plagiarism lecture can attest, copying is wrong—it’s cheating; it’s taking the easy way out. The issue, then, is what constitutes copying. And in creative disciplines, the line is hardly clear. Even Shakespeare had his sources, and Botticelli didn’t invent Venus. Which is not to equate even the loftiest of fashion designers with either, but rather to acknowledge their parallel reality: In fashion, as in other artistic disciplines, where one takes a reference can be as powerful as where it was found. Certainly in the emotional world of fashion, the topic is fodder for endless debate.

The issue exploded into prominence after Marc Jacobs’s spring 2008 show in New York, one this magazine and WWD loved, the latter noting its references as a creative strength. Some other critics, however, lambasted the designer for those references, citing John Galliano, Chanel and, most of all, Martin Margiela and Comme des Garçons’ Rei Kawakubo. “Most disappointing was that Jacobs spent a significant amount of time merely repeating or paraphrasing what [has already been] said aesthetically,” reviewed The Washington Post. “This collection seemed to emerge from the pages of other designers’ old sketchbooks.” But it was Suzy Menkes’s review in the Tribune—“A bad, sad show…an echo chamber of existing ideas,” she wrote—that drew a heated response from Jacobs.

“I’ve never denied how influenced I am by Margiela, by Rei Kawakubo; I don’t hide that,” Jacobs remarked to WWD. “I’m a designer living in this world who loves fashion. I’m attentive to what’s going on.… I have never insisted on my own creativity, as Chanel would say.” (He refers to a Coco bon mot: “Show me a man of originality, and I will show you a liar.”) A month after his controversial New York show, Jacobs would punctuate that statement with his Paris Louis Vuitton collection; the designer collaborated with none other than appropriation artist Richard Prince.

Throughout his career, Jacobs has admitted to being influenced by Yves Saint Laurent—also an obvious inspiration for Miuccia Prada, herself one of recent fashion’s most borrowed-from designers. In fact, she and Jacobs are among the rarefied few who are often applauded for spinning motifs sourced elsewhere into brilliant stories of their own.

But the bashing Jacobs took this season only proves that the critics’ love-hate relationship with derivation is an ever swinging pendulum. A designer may be lauded for appropriating one season—as happened when Jacobs’s Yves Saint Laurent/Walter Albini–inspired fall 2007 collection was nearly universally praised—and castigated the next. Over the years, many major designers have been so chided. Calvin Klein was at various times chastised for leaning toward Giorgio Armani and Helmut Lang; a retailer even termed his fall 1998 show “Comme des Calvin” for its strong Japanese motifs. Klein’s successor, Francisco Costa, has taken shots as well, most recently in spring 2007 for a stunning resemblance to Lang.

Ralph Lauren, whose look has inspired not just single collections but entire companies—most notably Tommy Hilfiger and Nautica—hasn’t been exempt either. Early in his 40-year career, Lauren was bashed by the English press for co-opting the artisto-Anglo look as his own. (“Bringing coal to Newcastle,” the designer can lightheartedly quip now.) And in 1994 he was famously sued by Yves Saint Laurent over a sleeveless tuxedo dress. Given that the suit was filed in a French court, it’s hardly surprising Lauren lost. Still, “it was totally ludicrous,” says Lauren. “You know, my first day of doing things, I made men’s wear for women and made evening clothes. Why would I want to rip off Saint Laurent? I never saw [his dress].”

And what of Ghesquière, one of the most imitated designers around? He’s launched legions of spacey androids, and next season his sculpted florals will no doubt find a fan base among knockoff lovers too. But in spring 2002 he starred in his own derivative debacle. That season hintmag.com revealed that some of his garments aped the work of deceased California designer Kaisik Wong, specifically a patchwork top from 1973. The Frenchman openly admitted the mistake at the time, explaining that when he saw an image of Wong’s garment, he assumed it was a theatrical costume.

Yet for that same collection, Ghesquière said he was inspired by another patchwork prince, Koos van den Akker, whose influence he acknowledged prior to the show. Had Ghesquière been aware of Wong, would it have made a difference if he had cited him as a reference as well? In other words, acknowledge the tribute and call it a day?

Were it so easy. Last fall Derek Lam received criticism from those who felt a twinge of déjà vu of the Balenciaga show four months earlier; for others, Lam’s wayward zippers, second-skin fabrics and high Eighties waists were textbook Azzedine Alaïa. The Tribune curtly opined that “Derek Lam was so into Alaïa [his collection] began to look like a job application.”

Ask Lam about it and he’s unabashed. “Definitely, I was looking at Alaïa,” he says. “That was the season everyone was talking about the weight issue with models. I wanted to use the philosophy of Azzedine—about empowering women through clothing that shows their strength and beauty. Perhaps the message I was proposing didn’t come across clearly enough.” As for what tipped the balance from inspiration to perceived plagiarism, Lam wonders if he should have provided show notes.

Though the creativity level and degree to which it’s done may vary, most designers lift a little here and there. “I think we would all be lying if we were to say we aren’t inspired by other designers’ work,” says Donatella Versace. Jacobs concurs: “The way I work is a product of what I’ve lived and experienced.”

Exactly, echoes Vera Wang. The inspiration-derivation divide is a hot topic for the designer, who’s been on the receiving end of some quite caustic reviews. Too much lifting from other designers, particularly Prada, goes the refrain. “It’s hurtful,” Wang admits, pointing out that her collection has always been based on her own personal style. “It’s an honest route because it’s how I dress.” More telling, though, is Wang’s elaboration on the point: “It’s how I’ve dressed in other eras, because I didn’t have my own collection when I was an editor.

“Nothing has never been done before,” Wang adds. “We’re dealing with the human body. You can lower the waistline down to your kneecaps or raise it all the way up to your neck, but unless a woman grows another leg or another arm or two heads, we’re still working within a certain structure.”

If that sounds like an easy out, it’s a concept virtually every designer brings up, even those much newer to the field. “This was a subject we talked about at [Parsons The New School for Design] all the time,” says Alexander Wang, who launched his line in 2004. “Everything is always compared to something people have seen before.” Case in point: his fall 2007 collection, which plainly tapped both Saint Laurent and Alaïa. “But I was trying to take that and make it street, put a hip-hop edge to it,” he explains.

Doo-Ri Chung notes that, as young designers, “we’re not going to invent the New Look. [That possibility] doesn’t exist anymore.”

Still, says Christian Lacroix, a designer has to at least put his or her own twist on a look. “Inspiration is not enough,” he says. “You have to bring your own strength, energy and imagination to push further. It’s like cooking. When you cook directly from a book, you just copy a recipe. When you adapt it, adding this spice or that ingredient with your own fantasy or intuition, you make the dish your own creation.”

Clearly, there are scores of designers who have riffed unapologetically on other designers’ standards. Anna Sui has her own particular take on Ossie Clark and Biba. And veritable legions, from Adolfo and St. John to Junya Watanabe and Yohji Yamamoto, have had their way with Chanel. Last fall Yamamoto glanced unmistakably toward Louis Vuitton with all-over double-Y logo patterns in a witty send-up of the famous monogram.

“Yves Saint Laurent, Madame Grès, Chanel—certain designers have gone into the history book,” says Tuleh’s Bryan Bradley.

“[These names are] part of the fashion vocabulary,” agrees Lam. “It’s like saying you can’t send jeans down the runway without deriving from Levi Strauss.”

Cynthia Rowley halfheartedly jokes that perhaps there should be a statute of limitations, after which ideas can enter the public domain. “To me,” she says, “the difference is timing.”

The fall 2007 Burberry Prorsum show makes for a perfect example. Christopher Bailey worked a medieval motif inspired by the house’s knight logo. The problem is that only the year before, Prada had spun a spectacular urban warrior tale of its own. “This was just too soon for Bailey to have launched a similar crusade,” declared WWD at the time. In response, Bailey says he hadn’t even seen the Prada collection in question. “I never looked at it,” he insists. “Very few designers ever go to any of the shows. But a lot of the journalists go from one show to another, so they have a bigger memory bank.

“Call it the zeitgeist,” adds Bailey, “but there are moments when several people are feeling the same thing.”

He has a point; isn’t that how trends are born? “Fashion is very mysterious,” says Diane von Furstenberg. “It is a mood, l’air du temps. Then come the silhouettes, cut, color, fabric.”

“Sometimes, you actually just arrive at something that somebody else has arrived at,” says Kerrigan. “If you’re influenced by rock ’n’ roll and punk, which a lot of us are, you’re going to arrive at a lot of the same things.” She does call attention to the fact, though, that for smaller concerns like hers, the inspiration-versus-derivation issue may sting a bit more. “Journalists don’t recognize the work of the smaller designers, only the bigger ones,” she says. “So even the small designers who are original, it can be said they copied somebody else. Or it’s like you’ve never done it at all.”

Maria Cornejo, whose Zero collection has become a favorite among young, in-the-know fashion lovers, maintains that more than one well-known designer has browsed her Mott Street shop, only to feature a design reminiscent of one of hers in a later season. She says she even contacted one such “fan” to tell him or her—she’s ultradiscreet—to stop. “And I’m not talking H&M or Zara—that’s different. I get upset when somebody on the same level as us, selling to the same stores, is, as you would call it, ‘directly inspired.’”

But sometimes designers can be inspired indirectly, and even unintentionally. Bradley notes that many stylists work with multiple designers. To wit, Lang’s longtime consultant Melanie Ward had a hand in several Calvin Klein shows, which could explain some of the commonalities. Designers also house-hop, as is the case with Paulo Melim Andersson, now in his second season at Chloé, where more than a few Marni-isms—vestiges of his last employer—found their way into his first collection. Several reviewers noted a certain Tom Ford influence on the Burberry Prorsum runways of late; prior to his current gig, Bailey spent six years working for the designer.

Not that Ford, often accused of seeing the world through Halston-colored glasses, would likely be up in arms about it. At a University of Southern California fashion conference in 2005, he remarked, “Nothing made me happier than to see something that I had done copied.… Appropriation has always been a trend.”

And at the end of the day, while fashion may debate the parameters of intellectual property, for most fashion-loving women, the derivative-or-not brouhaha is a nonissue. “The customer doesn’t care what something’s inspired by,” says Jacobs. “What matters is if they like it and feel good in it.”

Prada: Mauricio Miranda; Yves Saint Laurent, Comme des Garcons: firstview.com; Marc Jacobs: Talaya centeno; yohji Yamamoto: Giovanni Giannoni; Louis Vuitton: Stephane Feugere