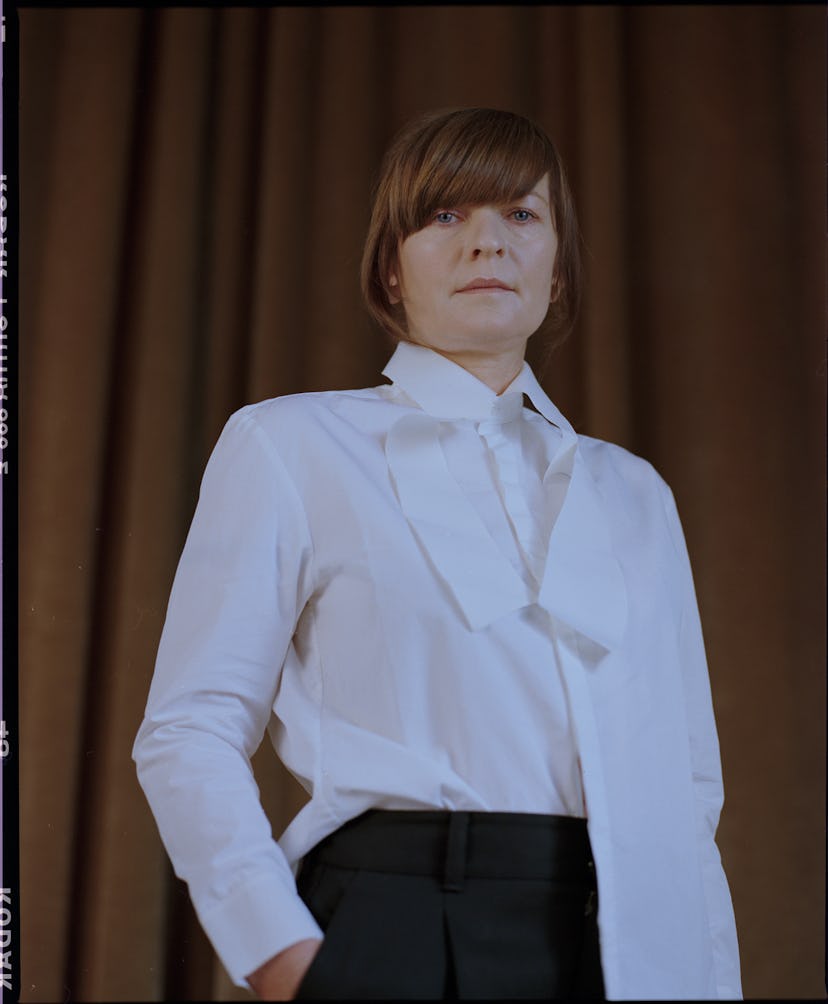

Meet Goshka Macuga, the Artist Whose Genius Is in the Footnotes

“I sometimes envy people who go to the studio and just make a painting,” says the artist, whose show “Time as Fabric” opened this week at the New Museum.

One of the first things the artist Goshka Macuga did when we met downstairs from where her floor-wide survey show at New York’s New Museum was being installed was hand me 18 highlighted pages of notes on her practice, which she suggested I peruse before we sat down to talk. They were as much for my reference, she explained, as for her own. Macuga’s works are so complicated, so intricate, that even the artist herself has trouble keeping all of her research straight.

“I spend sometimes from six months to a year even just to figure things out, studying and researching as you would do if you were writing something for purposes that aren’t necessarily visual,” she said. “To the Son of the Man Who Ate the Scroll,” for example, her current installation at the Prada Foundation, took a year and a half to produce, and it wasn’t even up to Macuga’s usual standards: the London-based Polish artist often bases her work on the history of the institutions she shows in, turning her 2011 show at Minneapolis’s Walker Arts Center, for example, into an examination of who exactly Thomas Barlow Walker was. The Prada Foundation’s permanent exhibition space, however, only opened last year, yet she still found a way to make it complicated: she examined the ideas of beginnings and ends, using everything from talking, humanoid robots to 3,000-year-old Sumerian tablets to machines that drew on scrolls to Egyptian sculptures borrowed from the Louvre.

“I sometimes envy people who go to the studio and just make a painting, and it’s more about what you see and how you feel about it,” Macuga said. “I really complicate my life enormously, and each time is like a new start, because I often get into working on things that I don’t have a clue how they function, and it’s a whole big process.”

Lately, that research has manifested in enormous woven tapestries, five of which are now stretching across the New Museum, some even spanning the width of the building. Because “Time as Fabric,” her first museum show in New York, was supposed to draw off existing work, she didn’t look into the New Museum’s past, but she does display her Walker Arts Center findings – a forest scene complete with everyone from Marcel Duchamp to Tea Party protestors – as well as her investigation of the international exhibition Documenta, which she criticized for organizing an outpost in Kabul, Afghanistan that year without properly acknowledging the “dodgy stuff” and context of the country’s war.

Before sending them to print in Belgium, Macuga stitches together and lays out the tapestry collages on her computer, but as usual with her, it’s never that simple: With the Documenta project, she still found it imperative to actually get together dozens of cultural figures in Afghanistan instead of resorting to Photoshop. “When I started working with this originally, I was more flexible with the illusion of reality wasn’t that important, and I was happy with some idea or indication of this might have happened,” she said of the often political scenes that she constructs. That attitude, however, is a thing of the past. She ended up organizing a catered, outdoor lunch in subzero temperature in the aftermath of a snowstorm that delayed her for three days. (She also put together a miniature newspaper titled “half-truth,” which the Documenta organizers begrudgingly handed out at the fair – along with their own printed defense.)

It’s quickly clear why Macuga, who is the definition of methodological, and too “obsessive” to allow herself to use social media, has also earned herself the title of curator and researcher. To her, however, they’re all connected, in the same manner as curatorial artists who owe a debt to Marcel Duchamp. She started off creating her own contexts with group shows and installations in flats and artist spaces around London, but changed tactics once her work shifted to museum and gallery settings. She has since become an artist of the school of institutional critique. “Of course all these institutions carried this history, and when you start looking at it, there’s always some sort of aspect worth looking into,” she said of how her work came to be more focused on politics about ten years ago. “It’s really about looking at the art as an institution.”

In addition to the five large-scale tapestries, her show at the New Museum also contains an hour-long video that’s a comedic criticism of the art world, as well the cut-outs of everyone from Angela Merkel to a snake-covered [Marina Abramovic](http://www.wmagazine.com/culture/art-and-design/2014/10/marina-abramovic-new-performance-art/) that make up its set. Macuga wrote it based off an informal play written by the German art historian Aby Warburg, whom she developed an interest in after discovering that his fascination with Hopi snake rituals was so extreme that he traveled to New Mexico when Western railroads were still being built in the U.S.

Unsurprisingly, Macuga added in another layer: She discovered that one of the negatives she purchased from a Vietnam War veteran featured him trying to put a snake in his mouth, signaling to her she should add in the American history of the Vietnam war. “Of course, the Hopis did the same thing with the snake dance, hanging rattlesnakes from their mouths, so it was like okay, this is it, I have to see this chance of these two things coming together,” she said excitedly.

“So when you you ask me about research,” Macuga said, after pausing for breath, “I sort of invented my own research as well a lot of different things for myself to guide the work or my existence within a subject.” As the dancers in Cally Spooner’s current installation slammed into a wall just a few feet away from us, Macuga gave no sign of noticing, as if to demonstrate her razor-sharp focus.

A self-described “child of communism,” Macuga has lived in London largely ever since the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, when she sought to leave Poland and “kind of get out of my own context,” she said. “All of my education until I was 19 was still in the old system, so I had to really define my relationship to history because the history I was studying in school … everything has been altered since.”

In a way, Macuga’s work, then, encourages the same sort of experience: “What I would like people to get out of this show, maybe, is some kind of question of our attitude to the truth, or how much we take what is given to us rather than investigating ourselves,” she said.

Meet Goshka Macuga, the Artist Whose Genius Is in the Footnotes

Goshka Macuga

“Of what is, that is; of what is not that is not 1,” 2012. Wool tapestry.Installation view, Goshka Macuga: Exhibit A, MCA Chicago.

“Death of Marxism, Women of All Lands Unite,” 2013, at the New Museum.

“The Letter,” 2011. Tapestry.

“On the Nature of the Beast,” 2009. Tapestry. Installation view, Goshka Macuga: Public Address, Lunds Konsthall.

“Preparatory Notes,” 2014, at the New Museum.

“Lost Forty,” 2011. Tapestry. T.B. Walker Acquisition Fund, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Installation view, Goshka Macuga: It Broke from Within, Walker Art Center.

“The Nature of the Beast,” 2009. Bronze sculpture on wooden plinth. Installation view, Goshka Macuga: The Nature of the Beast, Whitechapel Gallery.