How Did Remo Ruffini Turn the Humble Down Jacket into a Multibillion-Dollar Empire?

Remo Ruffini, the imperturbable entrepreneur and CEO of Moncler—presently one of the top luxury sportswear brands—lives quite consciously in two worlds. There is the intimate family world centered around Como, a city in Northern Italy, where he was born and still resides. And there is the bigger world outside Italy, where Ruffini, over the past dozen years, has built the French-Italian company into a $4.5 billion empire, with 181 shops, where customers are bewitched into buying the Moncler signature product—basically, a goose down ski jacket. A jacket, however, that under Ruffini’s tutelage has become what the French call la doudoune chic, and the Italians, il piumino di lusso (in other words, an object of desire that costs more than $1,000). A jacket seen not just on the slopes in Gstaad, but also at La Scala in Milan.

For Ruffini, life in the smaller world consists of workdays at Moncler’s Milan headquarters and quiet weekends with his wife, Francesca, and their sons, Pietro and Romeo. But his big world has as many facets as a disco ball: months of international travel; partying with celebrity fans, from Leonardo DiCaprio to Madonna to Kanye West to Lee Radziwill to Drake, who flaunts a Moncler puffer in his video “Hotline Bling”; conferring with the brand’s star designers, Giambattista Valli and Thom Browne; and hosting the huge events—more performance-art circuses than fashion shows—for which Moncler has become famous. Particularly gobsmacking are the New York presentations for the Moncler Grenoble line; attendees won’t soon forget the flash mob of 180 skiwear-clad dancers getting down in Grand Central Terminal in 2011, or last winter’s epic takeover of Lincoln Center, inspired by college marching bands.

It’s a breezy spring day in Como, and Ruffini is talking about life at Villa Palatina, his lakeside compound. He also has a chalet in Saint Moritz, a Milan pied-à-terre, and a newly acquired superyacht, the Atlante. But this graceful 19th-century villa, overlooking the Alps that once attracted European royalty, and more recently George Clooney, is what the Ruffinis call home. Traditional on the outside, inside it is all postmodern opulence—its dramatic marble floors and theatrical potted palms recognizable as the work of Gilles & Boissier, the Parisian design team responsible for the decor of not just Ruffini’s houses and yacht but also the Moncler headquarters and shops. At first glance, Ruffini seems like a typical rich outdoorsman without a thought in the world except where to stop for a bite on the piste. He’s tall and muscular, with a yachtsman’s beard and a skier’s ruddy perma-tan, and is dressed simply yet expensively in gray and navy. He is what Italians call alla mano—unpretentious, with an air of unflappable calm. It has been said that at fashion shows he looks almost out of place.

Over a lunch of sea bass and homemade pickled artichokes, Ruffini talks of his favorite spots, which are—not surprisingly—mainly northern: New England; Switzerland; the Nordic countries, particularly Iceland. He keeps track of temperatures and global weather patterns. “I’m fascinated by climates that are cool,” he says with a grin. “There is always a logic to someone’s tastes.” For inspiration, he prefers the vibrant atmosphere of cosmopolitan crossroads, where many different nationalities intersect, like London or Istanbul. He muses that Italy has cultural treasures and a great quality of life but has remained insular, “a prisoner of its own roots,” and admits that he sometimes daydreams of doing marketing for an Italian city—or the whole country. “Italy is an exceptional product we haven’t yet managed to sell.”

Ruffini’s childhood coincided with the Italian postwar economic boom. The family business was part of the centuries-old textile industry that once gave Como the nickname City of Silk. (The Missoni clan also has its roots here.) His grandfather owned a mill, and Ruffini’s father, Gianfranco, and his mother, Enrica, both founded eponymous clothing companies. Like many Italians in the fashion business, Ruffini grew up between the family house and the family factory. “I always lived in an atmosphere close to what I am doing nowadays,” he says. “My parents discussed work at dinner, so I was always talking about fabrics, about runway shows, about production, about PR, from the time I was tiny. It is a language very much my own.”

His parents separated in the 1970s, when Gianfranco moved his company to New York; there, one of his labels, Nik Nik, had success with an icon of the era, the silk disco shirt. Ruffini remained with his mother in Italy, finishing high school. At his father’s urging, he went to college in America, and his life changed. He didn’t study much—in fact, he hardly attended the one course he registered for at Boston University. What he found instead was a revelation: classic New England style. “When I got to Boston, I discovered preppies, Hyannisport, the Vineyard. This was the ’80s, and New England looked very different from New York. So elegant.”

Immediately he sought to bring the look to Italy. “I understood that there was a culture that I could communicate to an Italian consumer. This was a powerful emotion. It helped me come to the turning point of saying, ‘I won’t go to college—instead, I’ll start working.’ ” So, after just six months, Ruffini returned to Como and, with his mother as mentor, started a business. The plan was simple: a men’s line that merged American Ivy League style with Italian tailoring. He called it “New England” and presented it in a boutique in Portofino. The first collection featured Brooks Brothers–inspired shirts and khaki pants cut to a trim European fit and over-dyed in shades of blue. Yachting types adored them. The company grew to include a women’s line, and thrived until Ruffini sold it, in 2000.

“The reason, in my opinion, that New England was such a success is that we mixed American and Italian style,” says Ruffini, puffing on a black electronic cigarette. He pauses, his thoughts shifting to the similar road he has taken with Moncler. “Nowadays, we have such contrasts: Pharrell designing jackets for the mountains…I try to go outside of fashion. I’m always looking for new approaches, through art, and music, too. I think that if you don’t have this kind of merging, everything becomes too canonical.”

The French National Ski Team wearing Moncler, 1966.

By the time Ruffini was born, Moncler was already established as a European luxury label. Founded in 1952 by the French entrepreneur René Ramillon (the name is an abbreviation for Monestier-de-Clermont, an Alpine town), the company originated as a producer of outdoor equipment—tents, sleeping bags—and began to make down jackets at the request of the legendary French mountaineer Lionel Terray.

Soon there was a specialized line: Moncler Pour Lionel Terray. Italian and French mountaineers wore the gear through the ’50s and ’60s, and in the 1968 Winter Olympic Games, so did the French ski team. Jean-Claude Killy hung his three gold medals over a Moncler jacket. As Alpine holidays grew more popular, the company became a signifier of ski glamour. “Moncler!” reminisces the Italian-Texan socialite Michele Recchi. “You put on one of their jackets and felt like you were Grace Kelly at the Palace Hotel.”

At 14, Ruffini himself owned a prized puffer that he flaunted on his motorbike. In the ’80s, the jackets became an unofficial uniform for a posh group of teenage rebels nicknamed paninari, after Il Panino, a popular snack bar in Milan. The fad got so big that it inspired a song by the Pet Shop Boys, “Paninaro,” and spawned a rogue subculture of kids who slashed their puffers and covered them with graffiti.

By the end of the ’90s, however, Moncler was struggling, pinched between the viral expansion of luxury brands like Prada and Gucci and mega sportswear companies like the North Face. But in 2003, Ruffini arrived, determined to woo a broader range of consumers. When he and his backers bought the ailing label, it had total annual sales of about $62 million; by 2010, they were $368 million. “Other brands have a target,” he says, “perhaps a certain age group, people earning a certain amount of money. But I thought: We need to make something for skateboarding kids, for travelers, for the elegant lady who dines out.” The jackets became both more high-tech and more high fashion. He expanded aggressively, especially in the hungry new markets of Asia, and balanced tradition and innovation by creating distinct lines: Moncler Grenoble, the classic sportswear division; Gamme Rouge, the couture-ish women’s line, designed by Giambattista Valli; and Thom Browne’s daring Gamme Bleu men’s line. (Aside from Pharrell, there have also been collaborations with Junya Watanabe, Sacai’s Chitose Abe, Erdem Moralioglu, Masaaki Homma, the kooky Los Angeles collective FriendsWithYou, and most recently, Kanye West’s stylemeister, Virgil Abloh.) Less splashy but perhaps most remarkable of all is an ultralight collection called Longue Saison, which has somehow succeeded in getting people to consider down jackets a warm-weather staple.

Moncler Gamme Bleu, spring 2012, with Ruffini and Thom Browne.

In 2013, Ruffini took the company public, and its value shot up to $3.6 billion; with a reported 32 percent stake, he became a billionaire overnight. But business faltered the following year, after an Italian television show aired footage of inhumane methods used in Eastern Europe to collect goose down. Animal-rights activists called for a boycott of Moncler products and, despite the fact that representatives promptly demonstrated that the company used only humanely acquired goose down, share prices took a tumble. Moncler responded by issuing transparency updates on the provenance of its materials and opening its own certified down-preparation centers. In 2015, despite the global economic slowdown, sales rose once again. A store opened with fanfare in Tokyo—filling the Ginza district with emoticons—and a new American flagship is opening this month on New York’s Madison Avenue.

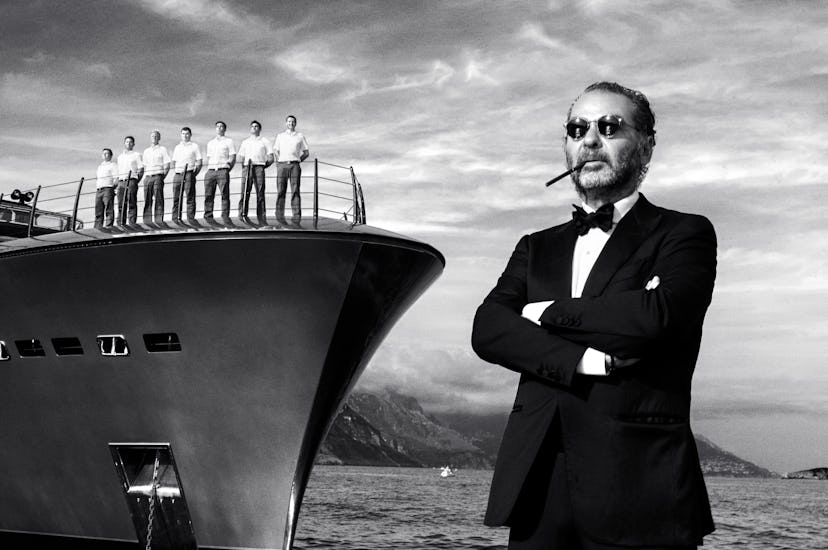

Ruffini’s yacht is the one place where his private and public worlds overlap. It serves as a vacation home, and also as a glamorous symbol of the Moncler brand. At 180 feet of Nuvolari Lenard design, it stands out from other megayachts with its dark color, huge windows, and high ride. It has been mistaken for a Greek navy boat, but the interior brings to mind a minimalist Marin County manse, with lots of pale wood and white furniture. “The Atlante was created from my personal idea,” Ruffini says. “I’ve had sailboats most of my life. But this time I wanted a boat like a house.”

On a blustery May afternoon in Cannes, Ruffini, wearing a cashmere pullover and shorts, sits barefoot on the stern deck, listening to a playlist of classic American rock (Kansas, Bruce Springsteen), chilling out in anticipation of a big evening as the host of the amfAR gala that closes the Cannes Film Festival. Behind him stretches the dreamy coastline between Antibes and Nice, dotted with monster yachts, including Roman Abramovich’s ocean-liner-size Eclipse.

In the air is a buzz of excitement over the gala, and a bustle of tenders transport makeup artists and hairdressers from the shore to the ladies in their cabins. On the Atlante, a couple of female guests have peeped out with Kabuki-esque masks on their faces, and soon, over the choppy waters, a bevy of seasick-looking stylists arrive, one with a pair of evening gowns rolled up under her arm like a bundle of laundry.

Ruffini talks of plans to explore the Baltic, but for now the boat remains close to Italy, for use on weekends. “I try to have what we call in Italian una cultura di buona vita. My life is concentrated not only on work but on my family, how I spend my free time. I think that to be lucid it is important not to overwork.” Relaxing onboard means beach visits and leisurely meals featuring Ruffini’s preferred Southern Italian dishes. (His favorite restaurant is the legendary Lo Scoglio, near Positano, which can be accessed only by boat.) In quiet moments, he finds time to read periodicals and watch the latest Italian indie films.

Pietro and Romeo, with the Atlante, in Capri.

The boat also provides bonding time for Ruffini’s close-knit, intensely private family. His wife, Francesca, runs her own clothing company, For Restless Sleepers, which specializes in luxury daytime pajamas and formal lounge wear made from Como-printed silk. Twenty-seven-year-old Pietro works as a consultant at the management firm Bain & Company, and Romeo, 24, as an analyst at Equinox Investments, a private equity firm. Asked if his sons are interested in the family business, Ruffini assumes a paternal tone. “Yes, they are. But I tell them, ‘If you work for us, you have to show your worth. You have to learn your trade first, and not inside my company.’ I don’t believe that the chair of command passes from father to son automatically. I don’t say no. But let’s see if they can do it.”

That night at the amfAR event in the gardens of the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc, celebrities are thick on the ground. The terraces blaze with giant emoticons from FriendsWithYou. Moët & Chandon flows, Dimitri From Paris spins, Kevin Spacey chitchats with Heidi Klum. From deep in a scrum of bejeweled women, Ruffini greets Leonardo DiCaprio. “I like seeing my friends,” Ruffini says. The swimming pool is lit magenta, with a huge Moncler logo; in the distance, under a full moon, glitters the Atlante.

Four weeks later, in Milan, Ruffini is surrounded by 40 male models arrayed as Boy Scouts. It is Men’s Fashion Week, and Thom Browne is presenting his latest fantasy foray into American nostalgia for Moncler Gamme Bleu. The cavernous auditorium is set up like a surreal summer camp: Under theater lights, an acre of real grass and pine trees is dotted with 40 pup tents. Ruffini observes gravely as the famous Belgian producer Etienne Russo hollers at the Brilliantined models not to lie down in the tents with their arms crossed like corpses. Ruffini displays easy camaraderie with Browne, who is doing last-minute tweaks. “Remo and I communicate with complete naturalness,” Browne says. “Nobody is like him in the way he is able to combine perfectionism in both product and marketing.”

Moncler Grenoble, fall 2016.

The guest list is the usual mix of Milanese and international fashion folk, enlivened by the basketball champion Serge Ibaka and the pop star Travis Mills, both sporting Moncler jackets. The lights dim, and to a mash-up of Mitteleuropean music, the Scouts enter, wearing Browne’s strange hybrids of sleeping bags and monastic-looking cagoules with hiking boots. Subtexts abound as two men costumed as bears unzip each bag and send the defrocked models marching toward their tents. Plaid, astrakhan—the styles are simultaneously witty, deranged, and somehow classic. And there is every possible permutation of ski jacket.

From his central seat, Ruffini looks on with a faint smile. This is his mixed-culture vision on the hoof: What could be more European than this fantasy of America? What could be more theatrical, more camp in all senses—and, at the same time, more commercial? I’m reminded of when we were discussing his very early days, when he launched New England with his mother. “I believe that the most important thing in the world is your roots—that is your identity,” he had told me then. “But at the same time, you have to have a contemporary vision, you have to mix cultures. Only then do you get that explosion of energy, of creativity.”

The History of Moncler

Remo Ruffini, with his yacht the Atlante and crew, in Capri.

Remo and Francesca Ruffini, at a friend’s wedding

The couple, with their dog Ulisse, in Saint-Moritz.

Ruffini and sons Pietro (right) and Romeo, in Saint-Moritz, 2014.

Pietro and Romeo, with the Atlante, in Capri.

Pietro, in Saint-Moritz, 2015.

The family, on the Atlante.

At the Lake Como house, a corridor with potted palms.

Francesca and Ulisse, by the pool

Classical touches abound.

The pool.

An exterior view.

A sitting area.

A Moncler promotional poster, 1952.

The French National Ski Team wearing Moncler, 1966.

Jacqueline Kennedy in Moncler, late 1950s.

A catalog cover, 1960.

An advertisement from the mid-’80s.

Moncler Gamme Rouge, spring 2016.

Moncler Gamme Rouge, spring 2011.

Moncler Grenoble, fall 2016.

Moncler Grenoble, fall 2011.

Moncler Gamme Bleu, spring 2012, with Ruffini and Thom Browne.

Moncler Gamme Bleu, fall 2015.

Watch W’s most popular videos here: