How Karl Lagerfeld Became Fashion’s Andy Warhol

Famed French Vogue editor Joan Juliet Buck remembers Karl’s early days, before he was Karl.

When I met Karl Lagerfeld in Paris in 1970, he was a freelance designer improbably starring in an Andy Warhol movie called L’Amour. He already had the aura of a star, a plump man with big biceps who defiantly described himself as “working class” because he designed anonymously for many brands. He proceeded along the Boulevard St. Germain like a boat in full sail, his coat flying, the lapels of his tailored suit festooned with red Bakelite pins, his hair and sideburns black, his glasses dark and his accent German. The great fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez and his partner Juan Ramos had introduced us, and, together with Anna Piaggi, Donna Jordan, and Corey Tippin, we’d all gather posing to the gills in our hats and costumes at the Café de Flore, where Karl picked up the check and then took us all out to dinner… then to dance… and, just before 2 a.m., to Le Drugstore to buy us all magazines. He never stopped.

Karl, an insomniac only child, took his sustenance from books, movies, music, and magazines. He spirited me off to the Cinemathèque to teach me about Louise Brooks and Fritz Lang, and to bookstores. He believed that you stayed open to inspiration by always producing, giving, letting go, and was relentlessly generous. He shared what he’d made and what he’d found in an endless spew of vintage couture, new sample dresses, pieces of fabric, pins and belts, sometimes throwing a dress onto the floor to set off a mad scramble between the women present. He loved tales of rivalry and one-upmanship between the turn-of-the-century courtesans Liane de Pougy and Cleo De Merode, and later, he would delight in masterminding fresh rivalries.

Karl Lagerfeld with Joan Juliet Buck at Lagerfeld’s apartment in St. Sulpice, Paris, 1976. Photo by Michael Childers.

He was relentlessly curious, and talked at a furious clip about everything that fascinated him—his new friend Marlene Dietrich, her stage dress made of a net called “soufflé,” the 18th-century Princess Palatine, Strauss’s opera Der Rosenkavalier. (He once confided to me, “I am the Marschallin.”)

When I stayed with Karl in the first of his apartments on the Rue de L’Université, there were no electric lights in the public rooms, only diptyque Santal candles set on the floor, perilously close to wafting taffeta curtains. He loved the 18th century and the 1930’s, and recreated those worlds around him. I slept under a baldaquin à la polonaise in the room next to the study-playroom-studio where he read and drew through his sleepless nights. Sample bottles of Chloe perfume collected in his bathroom off the little room where he slept in a bed that once belonged to Louis XV’s mistress, Madame de Pompadour. Karl always preferred small bedrooms; when he moved to a palatial part of the same building, he slept in a small bed in a room with nothing else in it.

Around 1975, he took up with Jacques De Bascher and began giving vast parties; for his Venetian ball at Le Palace, he wore a ruffled black taffeta domino and a tricorn, carried a fan, and, elegant, stayed in his car as his driver dropped off his friends at their own addresses before he went home to bed.

Lagerfeld with Princess Soraya at the Venetian Ball at the Palace in Paris in 1978.

He had the kind of eye that saw every bit of beauty and also every defect, and criticism became one of his art forms. He told me that my Dutch boyfriend had “all the energy of a dying tulip,” but for my wedding, to an Englishman, he not only designed my dress, but also flew me to Paris to choose the antique fabric, and then twice more for fittings. And it wasn’t a dress, it was a mauve silk riding habit.

Before Chanel, he was mostly known to insiders. “I don’t want to be in a museum, I don’t want to build an empire,” he’d say, a dig at Yves Saint Laurent, his perpetual rival ever since they’d both won fashion prizes as teenagers—Saint Laurent for a dress, Karl for a coat. He incited the Fendi sisters to shred, mangle, and knit together fur, did the same for leather for Mario Valentino, and for decades designed beautiful, slightly German Expressionist clothes for Chloe, with his recurring colors—black and tomato red, turquoise and yellow—but it wasn’t until he began designing for Chanel that he became world famous. And then he started powdering his hair.

Lagerfeld in Paris in 1983, the year he showed his first collection for Chanel.

One night at dinner in Monte Carlo in 1983 with Helmut and June Newton, we realized he’d fallen asleep behind his dark glasses. Chanel had launched him into a new dimension; his capacity for make-believe and his talent for costume would now fuel a multinational corporation.

He was mercurial, consistent in his curiosity, new passions, and perpetual motion, all of which were to keep boredom at bay. Hence the constant and obsessive reinvention of his world; once everything was in place, from muses to holiday houses, he had to fire the stars, strike the set, and start again; from Antonio and Juan to Anna Piaggi to Ines de la Fressange to Amanda Harlech, from a rented house in St. Tropez to a chateau in Brittany to a palatial villa above Monte Carlo to a timbered house by the sea in Biarritz. His friends and his surroundings were his mood boards, there to inspire and delight him until they no longer did, and he turned elsewhere for a new jolt .

At his Monte Carlo villa.

His apartment was a recreation of the 18th century until it became a recreation of the 19th century, and then he sold all the brown and all the velvet and launched himself into a modern universe with platinum-lined Ingo Maurer ceiling fixtures, around the same time that he discovered computers.

Technology thrilled him. His playroom-offices at Chanel filled up with the transparent, easel-set Mac desktops of the early 90’s at the same time as he began taking photographs, and, just as he couldn’t stop drawing all night, he couldn’t stop taking photographs and finding new things to do with them. He bought massive printers that made massive prints on special paper; he turned the photos of people and houses and gardens and empty places into books upon books, all while designing Chanel and Fendi and his own line, opening a bookstore, and flying around the world with his many iPods and even more books in tow.

How Karl Lagerfeld’s Signature Look Transformed Over the Years

Karl Lagerfeld wearing a simple black suit while accepting the First Prize in the Coat category at the Fashion Design Competition in Paris on December 11, 1954. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

In November 1973, Lagerfeld sported a full beard to match his thick head of hair. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

In 1979, the beard was shaved off, but his signature large black sunglasses are present. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

In 1983 Karl Lagerfeld joined Chanel as its chief artistic director fashion designer and donned the uniform—black suit jacket, black tie, and white shirt with a high collar. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

Lagerfeld shifted gears to a three piece suit later in 1983, and swapped out the black jacket and pants for grey. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

The suits got slouchier—and the colors lightened up—for Lagerfeld by the time 1988 rolled around. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

In the early 1990s, Lagerfeld made the move to all black, keeping the oversized frames, and adding a fan for his accessory. Top models Nadja Auermann, Claudia Schiffer and Christy Turlington posed with Lagerfeld during the Karl Lagerfeld Ready-to-Wear Winter fashion show 1992-1993 on March 1992 in Paris, France. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

With a full head of his iconic white hair, the designer swapped out his signature suit for a sleek black turtleneck à la Steve Jobs at the Karl Lagerfeld at the 2002 Spring-Summer ready to wear fashion show. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

In preparation for his photo exhibition titled Versailles à l’ombre du soleil in April 2008, Lagerfeld adhered to his classic uniform once again. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

Lagerfeld greeted the audience after his show for Lagerfeld Gallery while wearing a black suit jacket and white tuxedo shirt on October 4, 2002 during the spring/summer 2003 ready-to-wear collections in Paris. Incidentally, this also seemed to have marked Lagerfeld’s blue jean phase. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

Lagerfeld swapped out the signature black jacket for a crimson one at Art Basel in December 2002. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

The designer donned a sparkly suit—a departure from his mostly understated uniform—during a Paris Vogue Party on October 13, 2003 at the Plazza Athenee Hotel in Paris, France. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

Lagerfeld attended the 2004 Met Gala dressed in his shredded up interpretation of the theme “Dangerous Liasons: Fashion and Furniture in the 18th Century.”

Lagerfeld, his light beige suit jacket, tie, tight blue jeans, and his tan attended the Chanel Fall-Winter 2004-2005 Ready-to-Wear fashion show in Paris. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

For the Chanel 2008/09 Cruise Show in Miami, Lagerfeld’s tie grew wide, and his suit jacket remained as white as his signature ponytail. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

The designer went navy blue at the Cannes film festival in May 2015.

By 2016, it was all in the (jewel) details. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

In 2018, the beard returned once again, as did the richly detailed designs on Lagerfeld’s suits (this particular tie was embroidered with an image of his cat, Choupette) on November 22, 2018 in Paris. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

Lagerfeld went back to black once again, as he walked with his successor Virginie Viard on the runway during the Chanel show as part of the Paris Fashion Week Womenswear Spring/Summer 2019 on October 2, 2018 in Paris, France. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

And then he reinvented his body. In 2000, he wanted to wear the clothes that Hedi Slimane designed for underfed adolescents, and went on a radical diet that trimmed 90 pounds off his frame. He began to sport Chrome Hearts rings and fingerless leather gloves; when he was a child, his mother had said his hands were ugly, and now, nearing 70, he hid them. He had the collars of his shirts made higher and higher, he got a new apartment on the Quai Voltaire that he turned into a kind of spaceship. “I really like the idea of a second life,” he said to me, in 2008.

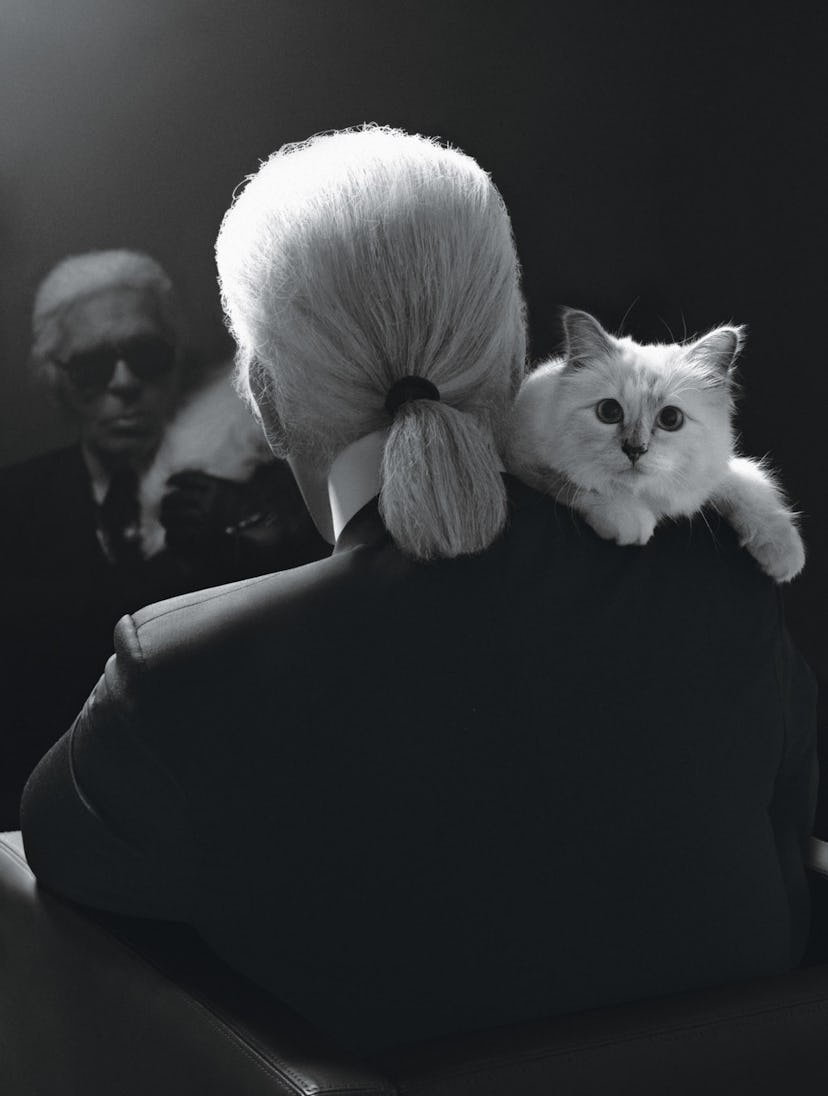

A few years later, the self-sufficient only child became a man with a cat, and he was by now so famous that Choupette became as famous as he was. His hallmark powdered hair and tight black clothes and dark glasses became his logo, shorthand for Karl Lagerfeld. The designer who’d said “I don’t want to build an empire” became something that hadn’t existed before, a designer who was, in and of himself, an empire. He’d been starring as himself in the increasingly frenetic records of his life from 1983 onwards, a total of 36 years in the brightest part of the brightest spotlight. Even Andy Warhol wasn’t that famous for that long in his lifetime.