Palm Springs Eternal

Havoc rules the world. Exotic is over. Risk is passe. ____Yachts the size of freighters clog the Caribbean bays, and there is nothing to do on those islands. The winter yearning for hot sunshine, pink flowers, and turquoise water has new requirements: easy access, calm, and safety; not just Wi-Fi but also culture; not just culture but also style; not just style but also glamour; not just glamour but also the dream of glamour. This brings us to Palm Springs, playground of stars since Hollywood began, and, suddenly, once again, the capital of cool.

Take this as a sign: Leonardo DiCaprio recently bought Dinah Shore’s Palm Springs house. So what does DiCaprio, movie star embodiment of ferocious uncertainty, mystery child-man in T-shirt and baseball cap, have in common with shellacked, peppy Shore, singer of 1948’s hit “Buttons and Bows,” TV star of the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, and long-standing date of Burt Reynolds? A midcentury house by the architect Donald Wexler with more than 7,000 square feet of right angles, spider-leg girders, and conversation pits, with a perfect view of the San Jacinto Mountains behind a cheerleader lineup of skinny palm trees.

The architects Richard Neutra, John Lautner, Albert Frey, Hugh Kaptur, William Krisel, E. Stewart Williams, and Wexler imposed a stark geometry on the desert to create the Palm Springs style: flat-roof houses (which Norman Mailer described as “carports” in his 1955 novel The Deer Park), glass walls that slide open to sprinklered grass, blocky structures made ethereal by diabolically precise geometry. So much glass and so much outdoors say that the surroundings are safe, benign, and, even if the Palm Springs summer heat can fry the brain, there’s plenty of air-conditioning.

Palm Springs is a playland where, from the Jazz Age onward, stars came to drink and carouse, have sex, and play tennis, golf, and polo. They were pals, intimates, cohorts—Shore, Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, Cary Grant, Lucille Ball, Zsa-Zsa Gabor, and, most of all, Frank Sinatra. In his house on East Alejo Road, Sinatra nursed Sammy Davis Jr. following a car accident, received Senator John F. Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, Ava Gardner, and, thanks to the composer Jimmy Van Heusen, innumerable hookers. There, the retired Greta Garbo and the aging Marlene Dietrich made out by the pool as Sinatra’s valet peered through the blinds.

The tycoons lived out their fantasies on a bigger scale than the talent. Darryl F. Zanuck, the cofounder of 20th Century Fox, pursued polo and croquet, like an English squire. Walt Disney rode his horses at his Smoke Tree Ranch, like a cowboy. Walter Annenberg, the owner of The Philadelphia Inquirer, TV Guide, Seventeen, and The Daily Racing Form, built a vast estate in Rancho Mirage, where he and his wife entertained the powerful: Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower, Richard and Pat Nixon, Gerald and Betty Ford, the Queen of England, and, for 18 New Year’s Eves, Ronald and Nancy Reagan.

Midcentury America exuded success and stability: houses, wives, country clubs, brunches, sports, Republicans, the square root of square, with an undertow of divorce, mobsters, and poontang. It was “Fly Me to the Moon,” nine irons, catgut, cocktails, “Mix me a stiff one, Sugar,” wing tip shoes sliding on terrazzofloors, mohair suits, Jax slacks, ice cubes and charm bracelets, Springolator mules, “You’re a scream,” hairdos and rollers, Pucci prints, “classy broad,” pastel convertibles, and “one for the road.” Giant lamps, free-form coffee tables, Milo Baughman benches, Finn Juhl dressers, yellow upholstery, and carpets that, to quote Mailer again, “felt like poodle wool.”

As the ’50s finally slid into the ’70s, newer stars—William Holden and Steve McQueen—moved into houses in Southridge, prime real estate with jetliner views of the entire Coachella Valley. McQueen rode his motorbike everywhere, Ali MacGraw behind him: two cool, rich, world-famous rebels. To MacGraw, the old golf and tennis players of Thunderbird Ranch and Rancho Mirage seemed like royalty. “I always had a sense that there was a Them,” she says, “that the apparently glamorous, and certainly rich, lives of those people were as removed from my reality as were the serious days of Old Hollywood. In that feeling was mystery, and curiosity, maybe a little envy, and, above all, a titillating sense of romance that was as far out of my own reach and lifestyle as the famous green light was to Gatsby.”

Slim Aarons’s 1970 photograph Poolside Gossip has become the quintessential image of high-class leisure, a primer on how to live like the rich. It shows two queens of Palm Springs society: Helen Kaptur, in a white lace pants outfit with a bare midriff, hair teased and fully lacquered, and Nelda Linsk, in yellow palazzo pants, hair teased and fully lacquered—both improbably lounging in full sunlight by Linsk’s seminal midcentury home, designed by Neutra, and known as the Kaufmann House.

But irony was creeping in. In 1971, Arthur Elrod’s spaceship of a house on Southridge Drive served as the villain Blofeld’s lair in the film Diamonds Are Forever. Nine years later, when John Lautner completed Bob Hope’s far, far bigger spaceship, a copper-roof airport-terminal aerie with a waterfall and a golf course, there were titters. Hope was in his 70s when he moved in but lived on for 23 years and enjoyed it until he died at the age of 100.

In the ’80s, Palm Springs became a slightly comic backwater, a desperate weekend choice, home to aged Republican golfers and the Betty Ford Center. There was little to do but get clean, get drunk, or visit the nearby Shields Date Garden to learn the difference between male and female date palms while drinking a date shake. Sonny Bono was the mayor. Scandinavians and Germans, lured by the prospect of 120-degree weather, were among the first summer visitors. Golf became fashionable again, and soon there were more than 100 golf courses kept green by water that California doesn’t have. Sprinklers changed the climate. The air is no longer as dry as crystal, but much of the electricity for the valley is produced by the 4,000 turbines of the wind farms, a vision of the future at San Gorgonio Mountain pass.

Stars grow old and die, but architecture has many lives: new and ugly, old and ugly—wait, no, that’s a classic! In the 1990s, midcentury modern became elegant in comparison to the clowning of postmodernism. It looked so minimal, decisive, pure. People began to buy up houses for less than $100,000. They were mainly gay men with an educated eye who responded to the style out there in the middle of the desert. That style became hard currency, the basis for the new perception of Palm Springs.

The chic have arrived once again, in search of the pink flowers, turquoise pools, and massive houses with perfect angles. Gays and straights, curators and consumers, cool-hunters and chillaxers are fresh blood for the real estate agents, among them Nelda Linsk from the Slim Aarons photograph, who went to work after her husband died because she was bored with playing tennis and going out to lunch. The Bob Hope house, recently the site of the Louis Vuitton Resort show, is for sale, at the reduced price of just under $25 million. Famous and anonymous residences change hands, money is made, architects are honored, experts in midcentury modern lecture at the annual Modernism Week show, which drew nearly 60,000 people in February.

The now magnificent and adventurous Palm Springs Art Museum boasts a theater bearing the name Annenberg. There is a separate building just for architecture and design. The Palm Springs International Film Festival attracts good foreign films. The Coachella music festival has become a dressier version of Burning Man. Along the good part of North Palm Canyon Drive, instead of Starbucks you’ll find intimate coffee shops interleaved with stores selling midcentury-modern artifacts, some new, some vintage. A store called Just Fabulous cannot keep Eric G. Meeks’s The Best Guide Ever to Palm Springs Celebrity Homes in stock. People want to know where Cary Grant once lived.

The old Rat Pack hangouts are closed—Don the Beachcomber, the Racquet Club, Sorrentino’s, Dominick’s, Ruby’s Dunes. Later ones remain: Le Vallauris, 42 years old, with good French food. Melvyn’s Restaurant and Lounge, where Mel Haber turned away McQueen and MacGraw on opening night in 1975 because they arrived in T-shirts and jeans. Everyone in Melvyn’s seems to be wearing aviator glasses, and they are all drunk. A woman lolls outside waiting for the Buzz bus, the trolley for those too gone to drive, to take her to the next bar, and declares, “Palm Springs is the beach without the ocean.”

The website Curbed reports that Leonardo DiCaprio is renting out the Dinah Shore house for $4,500 a night. He’s on to the next trend: Airbnb.

Photos: Palm Springs Eternal

Yul Brynner and Frank Sinatra (from left) at the singer’s Palm Springs home, 1971. Courtesy of John Bryson/Sygma/Corbis.

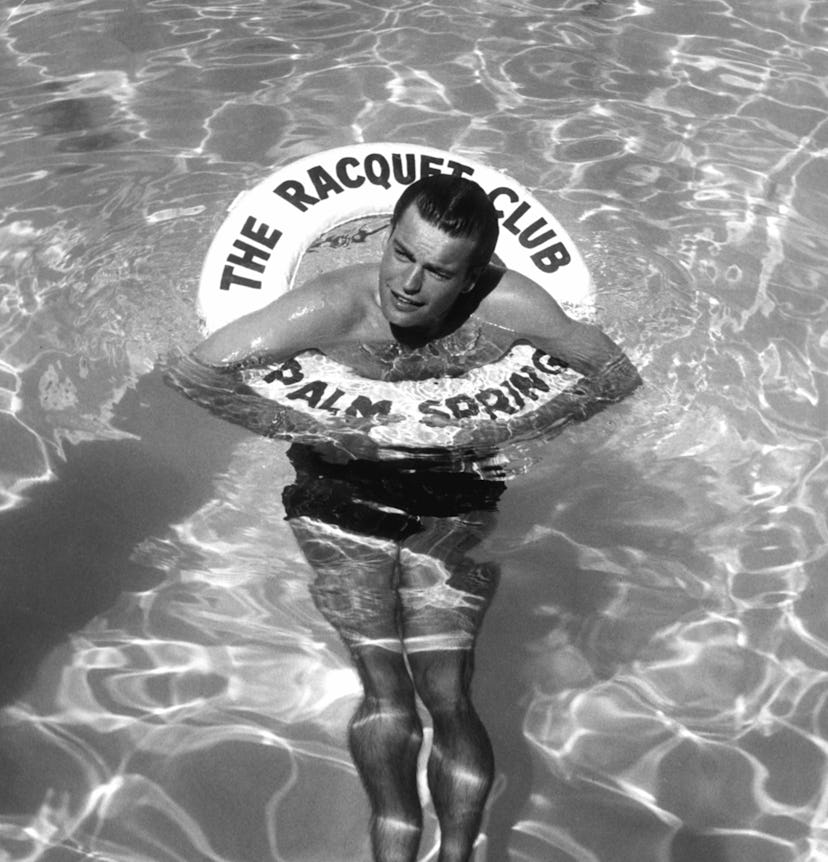

Robert Wagner in the Palm Springs Racquet Club swimming pool, 1956. Courtesy of Everett Collection.

A sunbather, 1949. Courtesy of Corbis.

The brise-soleil at the Parker hotel. Courtesy of The Parker.

The tennis star Eleanor Cushingham working on her tan, 1947. Courtesy of Peter Stackpole/Life Magazine/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images.

Marlene Dietrich and tennis star Fred Perry, 1934. Courtesy of Getty Images.

The scene at the Ocotillo Lodge pool, 1957. Courtesy of Palm Springs Life.

Slim Aarons’s Poolside Gossip, 1970, featuring Palm Springs social doyennes Helen Kaptur and Nelda Links (from left). Courtesy of Slim Aarons/Getty Images.

Doris Day and Marty Melcher at the Desert Inn, 1957. Courtesy of Neal Peters Collection.

The grounds of the Parker hotel. Courtesy of The Parker.

Corrine Krisel, the wife of the architect William Krisel, at the Twin Palms Houses, 1957. Courtesy of Julius Shulman.

Doris Day and June Allyson (from left), mid-1950s. Courtesy of Everett Collection.

The Frey House II, 1965. Courtesy of Julius Shulman.

The pool at Bob Hope’s estate, 2007. Courtesy of Julius Shulman.

A fur presentation, 1960. Courtesy of Getty Images.