In the eighties, a tight-knit group of London artists reveled in both the beautiful and the grotesque—and now they are having a second coming. At New York’s White Columns gallery, painter Nicola Tyson’s off-the-cuff photographs capture the early days of Billy’s, a London lesbian joint where such figures as Boy George could be seen taking baby steps toward gender-bending flamboyance and global pop stardom. At London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), meanwhile, a show of drawings and photographs honors Trojan, a painter and sculptor whose creativity and seductiveness captivated an underground scene that peaked with Taboo, Leigh Bowery’s legendary club.

The publication of Graham Smith’s 2011 We Can Be Heroes, a photo history of the post-punk and new-romantic movements, coupled with the screening of Charles Atlas’s documentary about Bowery, Trojan, and dancer Michael Clark at the Lucian Freud retrospective at London’s National Portrait Gallery earlier this year, has triggered the timely rediscovery of an era that nurtured talents from John Galliano to Alexander McQueen.

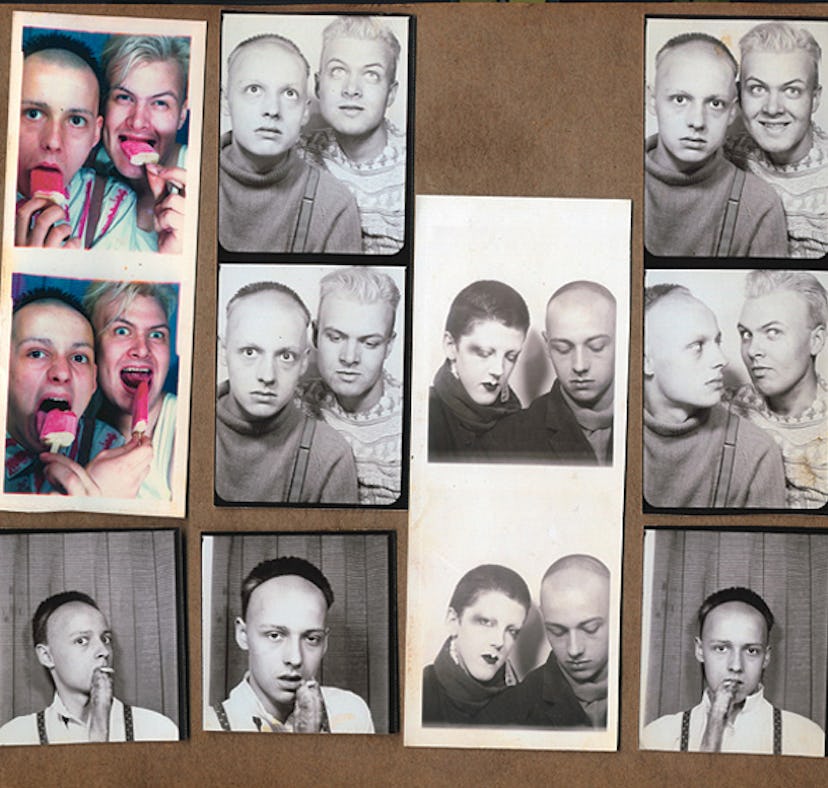

From top: Marilyn, Princess Julia, and Boy George (from left) at Billy’s Club, London, 1978; Trojan and Rachel Auburn (2), 1984.

Trojan, who died of a drug overdose in 1986 and was a onetime lover of Bowery’s as well as artist and filmmaker John Maybury’s boyfriend at the time of his death, left a body of work documenting a movement that sought to redefine the artistic life via outlandish experimentation and nonconformity. “It’s like falling through a keyhole into a wonderful moment when the most interesting, radical art wasn’t being made to be shown in galleries but was taking place in nightclubs,” says ICA director Gregor Muir.

The exhibition is drawn largely from Maybury’s personal collection of Trojan artifacts—the relics of their intense love affair. Many of Trojan’s full-scale canvases were either sold to anonymous collectors at his only gallery shows ever, in Florence and Tokyo in the early eighties, or dispersed after Bowery’s death a decade later. The ICA show concentrates on his portrait studies, which feature bizarre visions of one-eyed beings, syringes, gin bottles, and fried eggs.

Maybury’s photographs of his friends—some of them taken in photo booths, others during the gang’s elaborate costume and makeup preparations before their nocturnal adventures—offer a more intimate vision. In their Pakis From Outer Space phase, Trojan and Bowery dressed as Hindu deities Kali and Shiva, unveiling their ensembles at a party where most guests—in solidarity with miners protesting Margaret Thatcher’s reforms—were in jeans and donkey jackets.

If Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon fostered the idea of the artist in the gilded gutter, Trojan, Bowery (who would later become Freud’s gargantuan life model), Maybury, and Clark (whose sets Trojan dressed) followed their examples with unbridled enthusiasm. “It was a question of how far you could go,” recalls Maybury. “Sometimes it was about being beautiful and glamorous; other times it was about anti-glamour, anti-beauty, asexuality, and androgyny—not looking conventionally attractive. The last thing anyone wanted to look like was a model.” They delighted in being confrontational, not just visually but also verbally. (“Fuck off, freak!” Mick Jagger yelled at Bowery, who was dancing alongside him one night. “Fuck off, fossil!” was Bowery’s rejoinder.)

Nicola Tyson’s Dancing #3, 2012

“You wouldn’t want to take them on,” Tyson recalls. “They had no limits. It was just the way they entertained themselves.” “Bowie Nights,” Tyson’s show, focuses on this look-at-me culture just before their poses were perfected. By the time clubs like White Trash, Blitz, Anarchy, and Taboo came along, the outfits were more deliberate, and the venues were conceived as a stage for creative display. “I was just as happy showing my films in nightclubs or at underground raves like Jeremy Healy’s the Circus,” Maybury says. “It seemed just as legitimate as an art gallery, if not more so.”

For Trojan and Bowery, makeup and costumes were a means of artistic expression. “Trojan’s ideas came straight from the canvas and onto the face,” says Muir. “So on one level, we’re staging the first serious show of a makeup artist.” Trojan, who described his art as “fights and fucks in nightclubs,” also took the first steps toward body modification as contemporary art. “He got pissed off at people copying his look, so he decided to cut his ear off to see if they followed that,” Maybury recalls. “He got through cutting half the lobe off before fainting. Later he would paint it with glossy lipstick to make it look like a fresh cut.” (Bowery also embraced the idea of body modification, making holes in his cheeks to affix a joke-shop smile with huge safety pins.)

If famous British artists from the nineties like Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin were Thatcher’s children—well versed in ambition and careerism—then Tyson’s and Trojan’s exhibitions serve as a reminder that art and fashion can also thrive on the subversive edge of society. “We need to shake things up again,” Muir says. “A lot of people are starting to get worn out by art fairs and endless commercial exhibitions. It’s time to look elsewhere.”

“Nicola Tyson: Bowie Nights,” through December 8, whitecolumns.org; “Trojan: Works on Paper,” through November 18, ica.org.uk.

From top: courtesy of Ica and John Maybury/Trojan Archive (2); Courtesy of Nicola Tyson and Friedrich Petzel Gallery, NY; Nicola Tyson