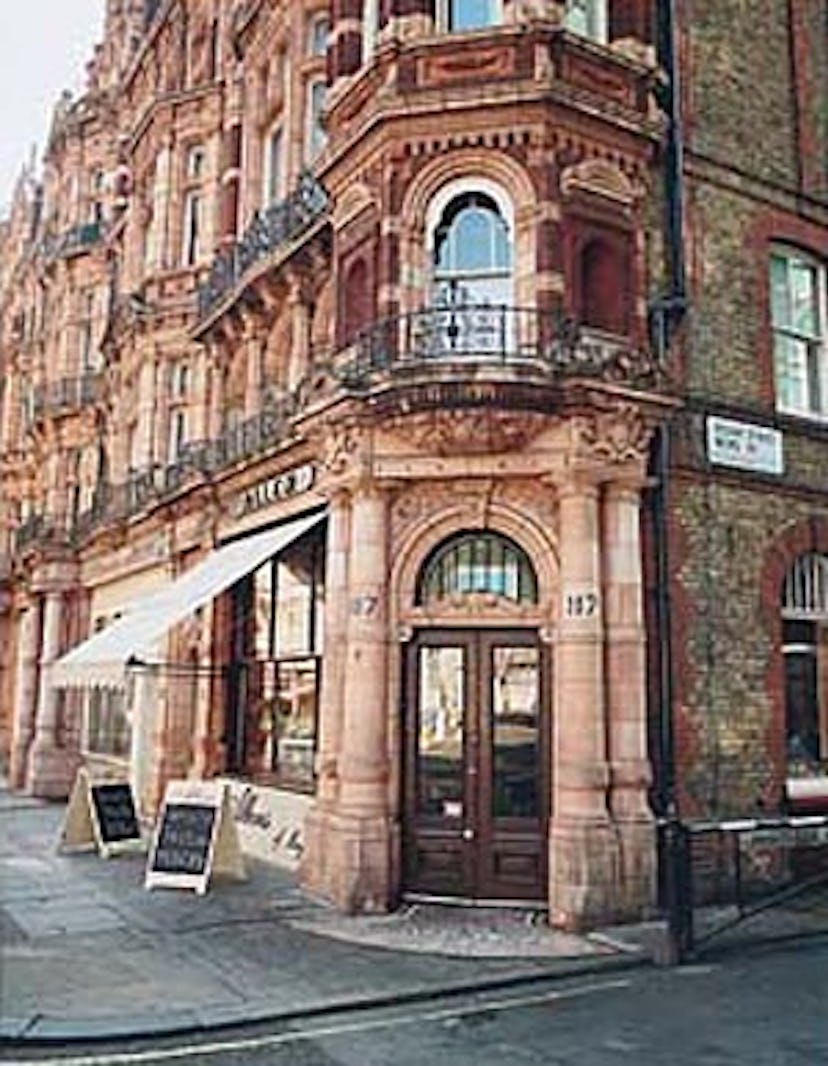

In a quiet corner of Mayfair, there’s a street that looks as if it’s been preserved under a Victorian bell jar, featuring Italianate and Franco-Flemish red-brick buildings, wide pavements and window boxes spilling geraniums and petunias. Among the oldest canopied shops on Mount Street are the Mayfair Pharmacy, with its enamel and badger-hair shaving brushes lined up in the window, and Allen’s of Mayfair, the 170-year-old butcher’s shop famous for its hung Scotch beef, salt-marsh lamb and grouse—favorites of London foodies including Prince Charles.

But this isn’t just another quaint pocket of London. Look a little closer, and there’s Marc Jacobs’s first store in England, which sits next to antiques dealer Kenneth Neame, whose windows are filled with tiny porcelain dogs set on gilt-edged mahogany armchairs. There’s also Emperor Moth, a quirky Russian clothing store with a surreal mirrored interior. At night, Scott’s, the newly reopened fish restaurant, is drawing London denizens including Kate Moss—who celebrated her birthday this year at the gleaming oyster bar—Jemima Khan, Lady Antonia Fraser and Harold Pinter. “The street is suddenly alive with celebrities,” says Jo Hansford, a hairdresser with a Mount Street salon who counts the Duchess of Cornwall among her clients. “The paparazzi are up here all the time.”

In the past year, Mount Street, 10 minutes from Bond Street—where Gucci, Louis Vuitton and Ralph Lauren have shops—and a short walk from Berkeley Square, has been undergoing a quiet transformation, which began when Marc Jacobs moved in to a former antiques store in February. It was a left-field choice for the designer, since most of his peers have gravitated toward other, more centrally located Mayfair streets, including Bond, Bruton, Albemarle, Dover and Conduit. But that didn’t matter to Robert Duffy, president of Marc Jacobs. “This area has more charm and appeal,” says Duffy. “There’s a garden around the corner. I like having a garden nearby. The retail spaces here are also beautiful, deep and interesting.”

Indeed, the Marc Jacobs shop boasts rich parquet flooring, grand Palladian windows at the back and period marble mantelpieces. Since Jacobs planted his flag, other fashion and beauty labels have rapidly followed. Balenciaga, Christian Louboutin, Dunhill and Aesop, the Sydney, Australia–based natural beauty line, have just secured spaces on the street, while Annick Goutal, the Paris fragrance house, is in talks about opening a store. Clements Ribeiro and Oscar de la Renta are among the many firms rumored to be looking for shops here too.

But Marc Jacobs isn’t the only spark behind the transformation. The owner of Mount Street, the Grosvenor Estate (its chairman, Gerald Grosvenor, the Duke of Westminster, is Britain’s richest landowner), has in the past two years actively sought to attract a mix of established and emerging fashion, jewelry, beauty and food stores in order to bring the street back to life. “We would not expect to see the same brands [that are] on the main thoroughfares, but rather niche brands,” says Keith Wilson of Wilson McHardy, retail leasing agent for the estate, who adds that what appeals to such brands is the “quintessential Englishness” of the street.

“You have a place for lunch, you have a place for shopping, you have a hotel, you have a park, you have a pub; it’s like a small family,” says Katia Gomiashvili, the Russian designer behind the Moscow-based label Emperor Moth, which sells whimsical velour track tops, some embellished with miniature fabric dolls. However, Gomiashvili admits that some shoppers were initially a little wary about checking out her collection of tracksuits and edgy printed Nina Donis dresses. “Our concept for the shop was very different from what was happening with the street, because it was mainly art galleries,” says Gomiashvili. “Customers were a bit scared to walk in, but on the third time [they go past], they’ll walk in,” she adds with a laugh.

Then there’s the fact that, while Mount Street’s bijou charm might match many designers’ dreams, its location, sandwiched between Berkeley Square and Park Lane, doesn’t draw the throngs of tourists and shoppers of Bond Street. But that’s the way its residents say they prefer it. “It’s like the ultimate gated community, an exclusive village,” says Paul Davies, a designer and developer. “Mayfair was originally designed for the most successful people in society, and now all the main hedge funds and financial institutions are here.” Davies is set to open a Maison of Luxury on the street later this year, in which designer Antony Price will operate his made-to-order business alongside real-estate and plane- leasing boutiques. “I just think it will become the Rodeo Drive of London,” Davies adds. “It’s not going to be a high-density shopping street, but I don’t think that’s what people want.”

To balance Mount Street’s traditionally elegant, old-world appeal with the allure of its fashionable new occupants, however, the estate plans to retain a number of the street’s long-term residents, including the stationers Mount Street Printers, which manufactures delicately embossed letterheads. “Grosvenor is very pragmatic,” notes Wilson. “They won’t impose [standardized] rents, as they appreciate that a florist can’t pay the same rent as someone who sells jewelry.”

That said, upping the glamour quotient on the street has led to an average rent increase of about 50 percent over the past 18 months, to around $360 per square foot, but this figure still represents less than half the cost of setting up shop nearby. “If you notice, there has been a downturn in other parts of Mayfair,” says William Asprey, chairman of William & Son, who opened his silverware and jewelry store at 14 Mount Street in 2000, after his family sold its share in Asprey & Garrard. “The rates on Bond Street have become far too high, and the street has lost its character and been taken over by the large brands.”

The Duke of Westminster, of course, has a vested interest in maintaining Mount Street’s rarefied village air, since the land it occupies has been in his family for generations. It was originally part of a parcel that has belonged to the Grosvenor family since 1677, when 21-year-old Sir Thomas Grosvenor married the 12-year-old heiress Mary Davies. Part of Davies’s dowry included 500 acres of farmland, then on the outskirts of London. It lay undeveloped until the early 1700s, when the Grosvenors began to build their estate around Grosvenor Square. Now the family’s former farmhouse, Bourdon House, which lies at the end of Mount Street, is set to open next year as Dunhill’s flagship, offering a store, private club, museum and apartments. “What price to pay to stay in an apartment which was [once] the bedroom of the Duke, complete with the original features and bells to the servants’ quarters?” says Wilson.

One of the most notable longtime residents is subtly updating its look too. The 108-year-old Connaught hotel, which earlier this year was the site of an after-party for the Marc by Marc Jacobs show, closed in March to undergo a facelift before reopening in December. The hotel group’s chief executive, Stephen Alden, however, was keen to ensure that the Connaught didn’t cast off its traditions. So he gave his most loyal guests a sneak peek at a model of the new bedrooms, complete with dark woods and refurbished antiques, before proceeding with the renovations. “It’s very much our guests’ sanctuary,” Alden explains. But he approves of the changes brewing in what he calls the hotel’s “magical setting.” “It’s exciting,” he says. “With the opening of Marc Jacobs, the street is evolving in the right direction.” After all, a neighborhood that turned from farmland to fine art without any major ado is likely to take its new role as a fashion destination in stride.

updat5