The Change Agent

Balenciaga’s Nicolas Ghesquière is one of only a handful of designers with the power to push fashion in new directions. Alice Rawsthorn meets Mr. Zeitgeist.

Fred raced into the drawing room looking very, very pleased with himself. Something dark and woolly was dangling from his mouth, and he ducked beneath a 1964 Gae Aulenti marble coffee table to play with it. “Oh, no!” wailed Nicolas Ghesquière. “What has he got now?” He crawled under the table to inspect the damage, only to see Fred escape. Tail wagging gleefully, the puppy treated himself to a couple of victory laps before leaping onto a 1971 Pierre Paulin Pumpkin chair and shredding his by now very soggy prey.

“He’s eating my sweater,” groaned Ghesquière, trying to look stern but failing hopelessly as he gazed, besotted, at the adorable chestnut-colored Labrador. “That’s his favorite game—taking something to play with and eating it. I took him to work at the studio, and he ate a pushpin. Drama! I had to take him to the veterinary hospital in the fabric truck.”

Unsurprisingly, Fred (full name: Frédéric) no longer accompanies Ghesquière to work at the studio where he reigns as creative director of Balenciaga. Instead he has run of the designer’s sumptuous apartment on the second floor (always the best one in Paris) of a resplendent 18th-century mansion on Quai Voltaire, across the Seine from the Louvre. Ghesquière found it last year after a five-year search, when one of Bernie Madoff’s victims was forced to sell. “It’s my big extravagance of the year,” he said happily. “It’s taking time to bring it back to life again, but it is absolutely fantastic. The walls. The floors. The fireplaces. The Louvre. The whole thing. It’s pure 18th century.”

So 18th century that much of the interior is protected by the French equivalent of landmarking, and Ghesquière has had to leave it intact. “I can’t touch the boiserie in the bedroom and drawing room,” he explained. “But some of the paneling in the office was removed, probably in the last century, and is now at the Metropolitan Museum in New York.” He is toying with commissioning an artist or architect to reinvent the office, and has filled the other rooms with treasures including more Paulin Pumpkins, some of Angelo Mangiarotti’s Seventies marble console tables, Eighties postmodernist pieces by Shiro Kuramata and Ettore Sottsass, and a gleaming white plastic Star Wars helmet above the bedroom fireplace. “When my grandmother came to stay, she asked what the vacuum cleaner was doing there,” he said, giggling.

Ghesquière, who turns 40 in May, is unquestionably one of the most important fashion designers today. “There are probably only five designers at any one time who count in terms of changing fashion by pushing it in a new direction, and Nicolas is definitely one,” said Lisa Armstrong, fashion editor of The Times of London. “He’s very, very influential and one of the most original voices in fashion.”

Ghesquière’s zest for research and experimentation has produced a stream of innovations at Balenciaga and persuaded legions of women to wear—or long to wear—a singular look that somehow manages to be strong, powerful, decadent, futuristic, chic, and consummately French all at once. Said look is usually accompanied by a heart-stoppingly outlandish pair of very high, quasi-orthopedic shoes.

“I just love following his work and being surprised by his ideas,” said his friend and sometime model, actress and musician Charlotte Gainsbourg. “Nicolas is a visionary and a perfectionist who makes me want to try things, to dare a little bit. Some of his clothes are like a second skin for me. I can get a bit fetishistic about them.”

Even sartorially challenged types, who may struggle to pronounce Ghesquière’s name (try guess-KEY-air), will recognize his innovations, if only from the knockoffs. Skinny school blazers. Cargo pants. Metallic leggings. Motorcycle jackets. Thigh-skimmingly short gladiator skirts and toga dresses. Those soft, slouchy rectangular leather Lariat bags that every other celeb is photographed with. In his 13-year tenure at Balenciaga, Ghesquière has invented or reinvented them all. Then there are the crazy shoes that look more like sculpture than footwear. Gladiator sandals with endless laces. Wedge-heel worker’s boots. Vertiginously high platforms and fetish heels that no self-respecting fashionista seems able to resist teetering around on—or falling off of.

Perhaps because a milestone birthday is approaching, Ghesquière now wants to up the ante. “This will be a year of transformation for me,” he pronounced. “There has been a big change in my team. Last year I stopped working with a lot of people who’d been with me for a long time, and I’m building a new team. I absolutely have to change my way of working. I need to become more strategic and delegate more. What’s the best way for a fashion designer to work today? To become a great craftsman like Alaïa, whom I love so much? Or a great brand like Armani, which I totally respect? My generation of designers has to do both. You have to have a complete emotional commitment to doing something very strong every season and to building a serious business.”

There’s no doubting Ghesquière’s determination to do both. “He is one of the very few people I know who has achieved precisely what they always wanted,” noted shoe designer Pierre Hardy, one of Ghesquière’s oldest friends and a former lover who now collaborates on Balenciaga’s ankle-imperiling footwear. “Nicolas is a kind of genius, and I don’t use that word very often. He has a great, great talent not only for inventing new looks every season but for managing teams of people and understanding every aspect of the brand. He’s very strong, very dynamic, very focused, very precise, and very demanding. There’s a Christopher Isherwood story about a butterfly with steel wings. Nicolas is exactly like that.”

All of which was evident in the quiet authority with which Ghesquière supervised a final fitting at his studio on rue du Cherche-Midi, near the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. Whether he was asking for a hem to be raised, a sweater to be shortened, shoulders to be cinched, a decorative motif to be moved (always by a few millimeters here or there), or buttons to be changed for ones of an ever so slightly different shade, he was gently firm and unerringly polite, phrasing instructions as questions and softening critiques with compliments.

Despite having all the steeliness you’d expect of someone intent on imposing his vision on the rest of us, Ghesquière is also sweet, warm, chatty, and giggly. He is small but strong (thanks to his love of swimming), and looks in person less conventionally handsome but more interesting than in photographs. He’s like a boyish Christian Bale, with straight dark hair, piercing blue eyes, and slender, slightly wonky features that reflect every emotion, looking different each time you see them. The boyishness is accentuated by his favorite uniform of white T-shirt, jeans, V-neck cashmere sweater (after Fred savaged the navy blue one, he quietly donned a dark gray clone), and New Balance sneakers.

Ghesquière was born in 1971 near Lille and raised in Loudun, a sleepy medieval town in the Loire valley. His father, who managed a golf club, wasn’t interested in fashion, but his mother was. “She was really into the whole late-Seventies thing of jersey dresses and synthetic turtleneck sweaters with flared trousers—not real fashion, obviously, but quite sleek and quite clean,” Ghesquière recalled. “She liked to dress me up. I have plenty of funny pictures of us on trips, with me and my older brother in matching clothes in different colors. We look like a typical Seventies French family in an ad campaign.”

By his early teens he was obsessed with drawing and fashion, poring over his mom’s copies of Elle and soaking up fashion coverage on French TV. At 14, Ghesquière persuaded his parents to let him apply for a summer internship with a Paris fashion house. “My father said, ‘Okay, you put some drawings together, and we’ll do a letter.’ One designer who came back to us was Agnès B.” He spent a month there and was then offered an internship with a new young designer, Corinne Cobson.

“For two years I worked for Corinne in Paris every weekend and every holiday, then went back to school in Loudun. When I left school she gave me a proper job and offered to pay for me to go to a private fashion school, Studio Berçot. I went for one day but didn’t enjoy it. They were all supercool, and I was too young, too provincial, and too into my work. Corinne was very sweet and very fun. She took me to the shows and to clubs like the Bains Douches and Le Palace. It was great but I missed my friends, so I went back to Loudun. Drama!”

He soon returned to Paris and, on the eve of his 19th birthday, began an internship at Jean Paul Gaultier. “It started out as a supersmall job, making coffee and dog walking, eventually doing color cards and photocopies, but it was fascinating. Gaultier was the place to be. It was a dream come true to go backstage at the show, to see the clothes in reality and the processes, and the way Jean Paul worked, always looking for strange combinations of ideas.”

After two years, Ghesquière left to freelance, designing mostly knitwear. “Even then he was a very, very hard worker, working late every day, drawing a lot, developing ideas and discussing them,” recalled stylist Marie-Amélie Sauvé, who befriended him at that time and still works with him at Balenciaga. “Nicolas was extremely curious about what was going on around him, always observing other people and learning from them.”

By then Ghesquière had fallen for Hardy, and he began a seven-year relationship with him. “Pierre was very important to me and still is,” he said. “He showed me so much. It was fantastic. We’d go to the ballet, the theater, exhibitions, and movies all the time. There’s a Belgian choreographer, Alain Platel, whose work I love, and we drove to Dijon for the night to see a performance.”

It was Hardy who tipped him off about a freelance job at Balenciaga. Under the brilliant, introspective Cristóbal Balenciaga, it had been one of the great Paris couture houses of the mid-20th century. But since his retirement in 1968, the house had declined. By the time Ghesquière arrived in 1995, it was reduced to living off licensing deals.

“Pierre said, ‘You know what, they’re looking for someone. But it’s not a cool job; it’s a licensing job. You’ll have to do wedding dresses and stuff like that.’ And I said, ‘It’s okay.’ I needed a new client, because I’d just lost a big one, and I thought there might be something interesting there. I could see, by watching the contemporary collections and also trying to learn about fashion history, that there was a strong connection between the work of the Nineties minimalists—Helmut Lang and Jil Sander—and Cristóbal Balenciaga.”

Ghesquière spent two days a week at Balenciaga, producing endless drawings of wedding dresses, shoes, and belts, mostly for Japanese licensees. The more he learned about Cristóbal Balenciaga, the more he admired his purism and technical ingenuity. Balenciaga had a ready-to-wear line, produced by Belgian designer Josephus Thimister, but he had fallen out with the owner, Jacques Konckier, who wanted to replace him with a bigger name, ideally Yohji Yamamoto or Helmut Lang. “I was excited,” recalled Ghesquière. “It was like, I might be an assistant to Helmut! He had a very, very interesting proposition for Balenciaga—just couture, no shows, and only 50 pieces.”

But none of the big names bit when Konckier fired Thimister in 1997, after a disastrous show where the music failed and some of the audience walked out. “It was a weird feeling,” said Ghesquière. “I felt horrible for him, but at the same time I was thinking, This is it. They’re going to give me the job.”

They did, but only for one season, because Konckier still hoped to hire Lang. The 25-year-old Ghesquière had less than four months to design the spring-summer 1998 collection from scratch. “I hate watching the video now,” he groaned. “They wanted the Opéra Bastille—wrong venue. They wanted the girls to walk in a circular thing—didn’t fit. Even the carpet was bad. When you’re a newcomer in Paris, the Chambre Syndicale puts you between two huge designers. You have no chance to get good girls, and the press is too busy to come. I hated that show but still love the clothes. I approached Balenciaga in the most religious way possible: very black, very monastic, a sharp line.”

The next season he ignored the Chambre Syndicale and chose his own slot. So much buzz built around Balenciaga’s brilliant young designer that, within a year, most of the global luxury groups were vying to hire him. “There were 15 days of my professional life when everyone called: Bernard Arnault [LVMH], Patrizio Bertelli [Prada], Tom Ford and Domenico De Sole [Gucci]. They all said: ‘We’ll give you whatever you want. Another house? Your own label?’ I decided to go with Tom and Domenico. I thought that, as Tom was a designer, they’d understand me.” Ghesquière did a deal with Gucci Group in which he agreed to resign from Balenciaga while De Sole negotiated to buy it. Gucci Group succeeded in 2001 and kept Ghesquière as creative director. Two years later, Ford and De Sole were ousted by French luxury conglomerate PPR, which has since helped Ghesquière rebuild Balenciaga.

It sounds like a fashion fairy tale, but the reality was much tougher. Ghesquière’s initial position at Balenciaga was so tenuous that he hedged his bets by also designing two Italian collections—Trussardi, then Callaghan—until 2001. By then Konckier had decided to sell and wanted Ghesquière to sign a five-year contract (the business would have been worth more with its star designer), only to discover the deal he’d done with Gucci. “They got a good price from Gucci, but they were so unhappy with what I’d done that they tortured me,” Ghesquière said. “They even sent a letter to my family.”

Then he fell out with Ford and De Sole. He wasn’t happy with Gucci’s production of Balenciaga’s clothing or the bags. He didn’t like the location of the first store they chose for him in New York, although De Sole immediately invited him to choose another site. “Looking back, I just didn’t understand their position, but I reacted very violently, and not in a good way. I was angry, isolated, and so unhappy that I decided to leave. Then Ford and De Sole left. I just locked myself away and worked, worked, worked. Everything is cleared up now. When I see Tom we laugh about it, and it’s always a pleasure to see Domenico.”

He also had a happy ending with PPR. “The first time I met François Pinault [PPR’s founder], he said: ‘We want to build something with your point of view. Tell us what you need, and we’ll take care of the numbers.’ And they have.”

Ghesquière has continued the work he began with Gucci, controlling every aspect of Balenciaga’s development. The Lariat bags are still the biggest moneymaker, although the shoes he designs with Hardy are the heaviest hitters in terms of buzz. “I’ve always had a thing about objects, and the shoes have become a sort of accumulation of that,” said Ghesquière. “They’re an incredible way of experimenting with extreme technologies.” Podiatrists, who have much to thank him for, will be alarmed to hear that Balenciaga’s shoes may become a little less extreme (at least in terms of height) in the future, starting with this summer’s flat biker boots.

Balenciaga’s surreally futuristic stores, each with a unique design concept, are the result of Ghesquière’s collaboration with French artist Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster. “Our first conversation lasted three hours,” Gonzalez-Foerster said. “Now we meet from time to time and have a very free conversation, a kind of delve through films, moments, objects, images. It has become an incredible playground for experimenting with light, material, colors, plants, science fiction.” Together they conceive each store as a fantasy landscape. Among the inspirations for the New York store in Chelsea are icebergs, the postmodernist architecture of U.S. retailer Best Products, and the rock sculptures of Arte Povera pioneer Piero Gilardi.

For the Balenciaga perfume, launched last year, Ghesquière flung himself into lengthy research with the “nose” Olivier Polge. He adopted the same approach for the new line of watches, which were inspired by the double dial of a clock in the original couture house. Next up are a new website, possibly an iPad app, and new stores, perhaps including a second one in New York.

Ghesquière has even redefined the role of the fashion collections. Most Paris houses use couture to generate media coverage and make their money from ready-to-wear, accessories, and the other lines. Ghesquière treats Balenciaga’s ready-to-wear like couture: experimental and mediagenic, but not necessarily commercial. It is bankrolled by the other less complex and less expensive lines, including capsule collections of Pants, Knits, and Silk (which are what their names suggest), and Edition, for which he and his team scour the archive and auction rooms for original Cristóbal designs that can be reproduced.

“It’s our tribute to Cristóbal,” Ghesquière explained. “We find something we like, one of his timeless couture pieces, and it’s almost a surgical process, because we open up the piece and look at everything, trying to analyze how he did it. The development takes time; usually the fabric is the most difficult because the yarns don’t exist anymore, and the quality of the weaving isn’t the same. Sometimes it can take a year to get it right, and although it’s, well, not exactly a peaceful process, it’s a relief compared to the rush of trying to find new ideas.”

Though that’s where he excels. The heart of the new Balenciaga is what he calls “our crazy laboratory,” the studio where he and his designers experiment with new fabrics, processes, finishes, and shapes. Ghesquière’s innovations are often rooted in his obsessions. He loves movies, especially science fiction and those directed by Brian De Palma, Dario Argento, Stanley Kubrick, Claude Chabrol, and Jacques Audiard. A particular fascination is the parallel between the monastic robes worn by characters in sci-fi films like Star Wars and Cristóbal Balenciaga’s reinterpretations of the monks’ cloaks in the paintings of 17th-century Spanish artist Francisco de Zurbarán.

Another passion is design, especially the work of such postmodernists as Sottsass, Kuramata, and Alessandro Mendini. “I love the insane collage of Mendini’s work and Sottsass’s for Memphis,” he said. “It was Pierre [Hardy] who introduced me to Kuramata. When I was living with him, he had some amazing pieces. The funny thing is that I didn’t get it when I was younger. I thought it was the ugliest furniture I’d ever seen, and said: ‘Pierre, I think we should put this in storage.’ He didn’t, and I changed. Now I think it’s beautiful.” Ghesquière trawls the Web for work by favorite designers and always pops upstairs to the Demisch Danant design gallery when visiting Balenciaga’s New York store. He bought the first of his Paulin Pumpkins there. Another favorite source is the Nilufar design gallery in Milan, where he discovered a collection of furniture made by Italian designer Martino Gamper from remnants of the dismantled interior of a 1962 hotel designed by architect Gio Ponti—it became the inspiration for last fall’s color-blocked shoes.

As Balenciaga has grown, Ghesquière’s work schedule has become ever more onerous. Most weeks are spent in Paris, with occasional weekends at his country house in the medieval town of Montfort l’Amaury. For eight years he dated James Kaliardos, a makeup artist and cofounder of Visionaire, a New York–based fashion and art publication, and the two remain close. Left to his own devices, Ghesquière admits he’d work nonstop. “I have one friend who kidnaps me sometimes,” he said. “She shows up and says: ‘So-and-so is performing at Théâtre du Châtelet. I’ve got the tickets and you’re coming with me. No excuses.’ I love that. Otherwise, yes, I’d be working.”

Often his collaborators bring things to inspire him. He and Hardy based one style of shoe on an unusual snowboard binding the latter had spotted in New York and another on the jewel-like colors of a Rachel Whiteread sculpture. Gonzalez-Foerster often shows him such intriguing things as swatches of weird fabrics to help with the fashion collections as well as the stores.

But many of Ghesquière’s innovations emerge as works in progress during the design process, which can be intense and laborious. He worked round-the-clock for days to build last season’s color-blocked shoes from resin, plywood, and Formica, and once waited for 18 months to find exactly the right shade of green dye to reproduce a vintage lace dress for the Edition collection. “Nicolas is so tenacious and so persistent that he never, ever gives up,” said Sauvé. “If he has difficulty making, say, part of a jacket, he will try and try and try until he succeeds, no matter how long it takes.”

Take the checked coatdress with which he opened the spring-summer 2011 show. “The first idea was, Let’s try to do an organza dress in the leaf shape that Cristóbal often did,” he explained. “I’m like, ‘Mmm, mmm. Non! It’s not a dress; it’s a coat.’ The second step was to build a coatdress. The third step was: ‘Organza is awful. It’s so couture. Let’s find another fabric, some synthetic rubber or plastic thing.’ The next step was to try a print, but that wasn’t working, so we used this flat technique of Swiss mechanical embroidery instead. Then we develop the check. Then we start to build the shape. Then we use magnets to flatten the closure.

“After all that work, which isn’t cheap, I felt the whole plastic thing looked a bit Seventies tacky,” he continued. “So I thought, We need a beautiful plain black leather for the sleeves and collar. Then we did a whole session to choose a contrasting color for the stitching. Then we worked on the collar, which was inspired by one in a Diane Arbus photograph. It all took about three months, and maybe 20 or 25 fittings.”

The coat now retails for $1,835, although Ghesquière reckons that, with another three weeks of work, he could have reduced the price significantly. Critically, he doesn’t expect to sell the extreme pieces from the runway collection or the wilder shoes. “Development is very expensive, and can be very challenging and very painful,” he said. “That’s my job, to push and push. Even if 98 percent of people don’t understand what you’ve done this season, maybe they will next season. Sometimes the complex pieces disappear, but you can extract an idea that becomes generic, like the Lariat bag or the Perfecto leather jacket. No one noticed it the first season; then we did it again in exactly the same shape and details but softer leather, and it became a best-seller.”

All of the designers he admires share his commitment to research. “Issey Miyake’s fabric development was incredible,” he said. “I love Azzedine’s quality of execution and Versace’s too. I have huge respect for Jean Paul, and Helmut Lang for his quiet revolution. Rei Kawakubo is brilliant. Miuccia Prada also for building a huge brand with a soul. And Raf Simons is always challenging.” Ever the sci-fi geek, he is fascinated by the chapter of Sixties fashion history when André Courrèges, Pierre Cardin, and Emanuel Ungaro were inspired by the space race. But above all, he is devoted to Balenciaga.

“It’s impossible to be bored with Cristóbal. No other designer compares to him. Every time I go to the archive, I see something different. When I was in New York in December, I went with James to see Hamish Bowles’s little exhibition on Cristóbal at the Queen Sofía Spanish Institute. It was quite fantastic. The radicalism. The modernity. The touch and mass of the fabric. And I felt so proud.”

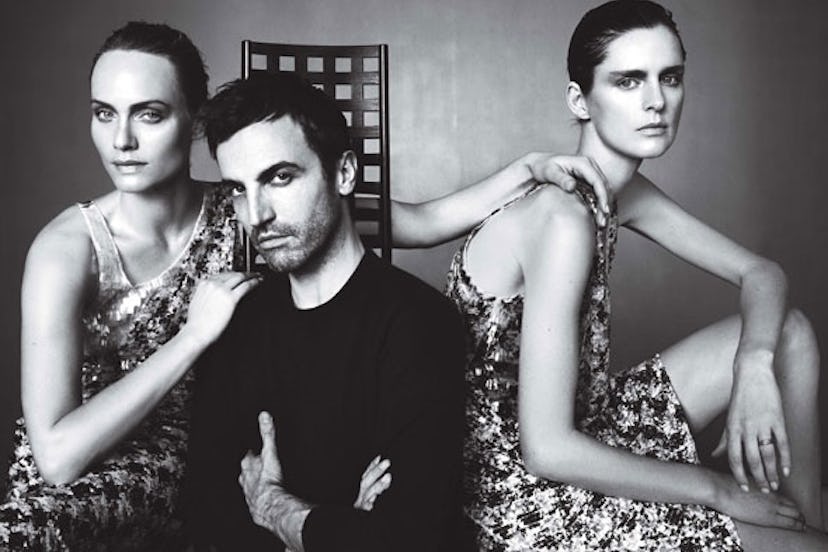

Balenciaga’s Nicolas Ghesquiere

Balenciaga by Nicolas Ghesquière’s multicolored sequined dresses.

Balenciaga by Nicolas Ghesquière’s polyester and nylon crepe jacket, polyester shirt with metal detail, PVC shorts, and ring. Polyester dresses and watch.

Beauty Note: A dose of Darphin Hydraskin serum provides a serious surge of hydration.

Balenciaga by Nicolas Ghesquière’s black and gray PVC sleeveless jacket, skirt, and boots. Silver python and black leather vest, navy blue and white polyamide shirt with metal detail, black gabardine pants, watch, and boots. Black patent-leather jacket, black and white polyamide shirt with metal detail, black gabardine pants, watch, and boots. Black and white sleeveless silk and cotton knit top, black and white polyamide shirt with metal detail, black gabardine pants, watch, and boots.

Beauty Note: Keep intense hair color from fading with Oribe Hair Masque for Beautiful Color.

Balenciaga by Nicolas Ghesquière’s leather and PVC coats.

Hair by Guido for Redken; makeup by Pat McGrath for Cover Girl; hair color by Laurie Foley for Wella Professionals at L’Atelier de Laurie; manicures by Jin Soon for Jin Soon Natural Hand & Foot Spa. Models: Amber Valletta, Stella Tennant, Milou van Groesen, and Saskia de Brauw, all at DNA; Freja Beha Erichsen at IMG; Delphine Bafort at Ford; Arizona Muse at Next; Eliza Cummings at Women; Bambi Northwood-Blyth at Elite; Jana Knauerova at New York Models; Aymeline Valade at Women Paris. Casting by Ashley Brokaw. Set Design by Mary Howard; production by PRODn @ Art + Commerce; digital technician: Noah Esperas. Photography assistants: Stas Komarovski, Dima Hohlovs, and Victor Gutierrez.