On Bastille Day, July 14, French citizens watching the giant parade on Paris’s Champs-Elysées will surely marvel at the taut precision of marching cadets, the rumble of the passing tanks and the daring flying formations overhead. But the $64,000 question—and feel free to add a few more zeros in terms of publicity value—is what first lady and former supermodel Carla Bruni-Sarkozy might wear to accompany her husband, French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who is often decked out in Prada or Dior Homme.

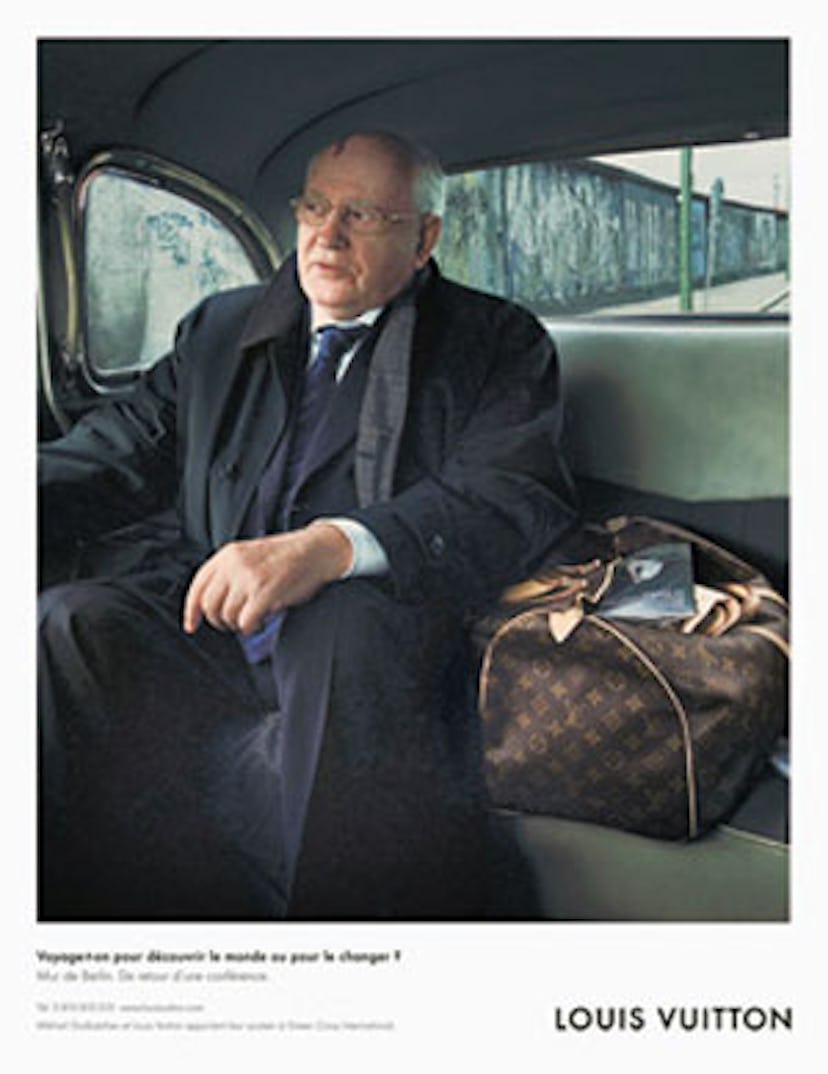

Political figures seem to be the latest frontier for designers, particularly in style-obsessed France. After all, it’s from there that Dior issued no fewer than five press releases detailing the outfits Bruni-Sarkozy wore during an official visit to London, and where Louis Vuitton tapped former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev as a poster boy for its monogrammed leather goods, and where justice minister Rachida Dati looks red-carpet ready whether she’s visiting a prison or posing for paparazzi on her way to a state dinner.

The trend is likely to spread to other nations at a time when more women are gaining political power and a celebrity-obsessed public is scrutinizing the style of world leaders almost as closely as that of Hollywood stars. Whether this is a good idea is a subject that’s already generating lively debate, even as designers begin jockeying for credits.

“When powerful women start using glamour and style, things usually end in tears. Marie Antoinette—hello!” warns Simon Doonan, the outspoken creative director of Barneys New York. “If they start shilling for fashion houses, then I will go live in Patagonia. [Political figures] should strive to be unremarkable and uninteresting in their style choices.”

Try telling that to the media, which makes much ado about political style—good or bad—from the chic outfits and signature hair braid of Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko to the swimsuit German Chancellor Angela Merkel chose for a recent summer vacation. (The cheeky British tabloid The Sun published a photo of her wearing it with the outrageous headline i’m big in the bumdestag.)

But Karl Lagerfeld, for one, isn’t surprised that fashion houses are in hot pursuit of high-profile figures from the political realm. “They have to wear something, and when they look good, people ask what they are wearing. It’s normal,” he says. “That is the way the world, our world, is today. We live in a visual world. You don’t have to be out of fashion to be taken seriously.” Smart politicos, he says, should not be “fashion victims, but women from today, chic and modern.”

Designers would prefer not to address the fact that certain political figures and first ladies are more gifted in the natural-assets department than others, Bruni-Sarkozy being at the would-look-good-in-a-gunnysack pinnacle. But everyone can benefit from good tailoring, says Lagerfeld, calling the proportions of the pants worn by Hillary Clinton and Merkel “terrible” and adding, “Someone should fit them—seriously.”

As for Michelle Obama, Lagerfeld describes her as a “handsome woman, but with no fashion image yet.” He continues, “That will come with the function, I hope.”

While his lock on Hollywood is well known, Giorgio Armani has also dressed Condoleezza Rice, Nancy Pelosi and Maria Shriver—as well as Clinton and Merkel—a feat he characterizes simply as “giving a helping hand” to women in important positions. His newest recruit is 32-year-old Mara Carfagna, Italy’s stunning new minister for equal opportunities, a former model and television starlet who chose a pale, curve-hugging Armani pantsuit for her swearing-in ceremony in May. “Politicians are real people going about their work in the real world,” Armani says. “There is no reason why a female politician should not be able to express her own style just as another woman in the workplace.”

From her pink-walled, prism-filled headquarters in New York’s Meatpacking District, Diane von Furstenberg points out that putting one’s threads on the backs of the powerful is a very old tradition, dating back to the days of Europe’s czars and kings. “You know where the word ‘royalties’ comes from?” she asks in her seductive, come-hither voice, smoothing back a few errant curls as she recounts how kings created the payment scheme whereby companies that made rugs, tableware and the like could market themselves as “suppliers to the court” in exchange for payments. “It’s absolutely a normal thing to do,” says von Furstenberg, who dressed Betty Ford in the Seventies and dresses a number of European royals today, among them Crown Princesses Victoria of Sweden and Mary of Denmark. “Anybody in power, they have their own personality and therefore they wear what fits their personality. That’s what clothes are about.”

Arguably, political figures today enjoy more fashion latitude than ever, which opens the door for designers to showcase the latest trends—up to a point. While women might have felt compelled to wear pants and power suits when they first conquered the corridors of the corporate world in the Seventies and Eighties, “today for a woman, even in the workplace, looking feminine and looking great is an asset,” figures Oscar de la Renta, the go-to guy for scores of American politicians, several first ladies and even first daughter Jenna Bush, who walked down the aisle at her May wedding in a slender, embroidered white silk organza de la Renta gown. “They should [dress well], for their sake and our sake.”

And de la Renta is well aware that their votes of confidence boost his profile in stores. “Fashion is nonpolitical; it’s commerce,” he says between fittings for his cruise collection. “Any kind of publicity like that, from the left or the right, is good. It creates public awareness of the clothes.”

On the other hand, some designers are notably reticent about being associated with the Bush administration. In February, for instance, when Laura Bush hosted a reception at the White House for the Heart Truth campaign, which spotlights women and their risk of heart disease, many did not attend.

But just how far public figures should go in making fashion statements is also a divisive issue. Donna Karan, who presciently had model Rosemary McGrotha portray a female president in a 1992 advertising campaign, says it’s imperative that a woman feel at ease in her choice of clothing. “It’s not about a fashion statement or a trend,” she explains. “It’s how you present yourself outwardly, and you have to feel comfortable. You have to know yourself.”

Armani’s advice: “My recommended approach would be to choose quiet sophistication and elegance over showmanship. I think Condoleezza Rice has in some ways set a standard that some others have followed.”

Meanwhile, despite his own baroque, maximal approach to fashion, Christian Lacroix agrees that women on the public stage should err on the side of discretion. “We all enjoy nice-looking, well-dressed women in powerful positions—and allure is part of the charismatic nature of their role,” says the designer, whose fashion fans include French culture and communications minister Christine Albanel. “They above all have to be free, faithful to themselves, disconnected from a too razzle-dazzle, vulgar, fake fashion scene.”

Christophe Girard, deputy mayor of Paris in charge of culture, who is also a director of fashion strategy at luxury giant LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, straddles both worlds and insists it’s all a question of balance. “Political life is no longer separated from real life, and political women and men know their image matters like [those of] a model or an actor to attract the public,” he says. “But it’s a real danger when politicians are more concerned about their image than their ideas.” For his part, Girard says he’s careful to choose outfits that match the various constituents he meets: “For young artists, I dress more casual; unions, more strict.”

In France, presidential wives have a history of accepting free clothes, something that’s more likely to raise eyebrows in Anglo-Saxon countries. De la Renta recalls seeing Danielle Mitterrand, whose politics he describes as “to the left of Fidel Castro,” wearing Yves Saint Laurent couture ensembles worth tens of thousands of dollars, “and everyone found it very normal.” But Girard figures anyone who represents the “general interest” should follow a strict policy of total transparency and accept only small gifts. “This is where suspicion of corruption starts,” he says.

Donatella Versace, of all people, also counsels caution, and on an unexpected front: “Generally speaking, I would not recommend those in public life to dress in too sexy a way, as they need to maintain a degree of gravitas, and looking too seductive might encourage people to take them less seriously. If you are not in control of your appearance, maybe you will not be that organized and efficient when it comes to matters of state.”

Yet Versace defends Dati and other glamorous French cabinet ministers like Rama Yade, the minister of state for foreign affairs and human rights, who looks like a movie star when she puts on a gown for important functions. “The idea that because you are a high-profile, professional woman you are not allowed to look glamorous is pure nonsense—and deeply sexist,” Versace says. “I thought we had moved on from that.” Versace certainly has, winning fashion credits for dressing Sarkozy’s ex-wife Cécilia Ciganer-Albéniz when she wed public-relations executive Richard Attias and expressing ambitions to dress the current Mrs. Sarkozy as well.

Look out, too, for more political figures and other leaders in fashion advertising. Environmentalist Robert F. Kennedy Jr., for instance, has already appeared in ads for Condé Nast Traveler and fashion brand Gant, which put Camelot in casual wear in 2006. And some are now setting the bar even higher. Antoine Arnault, director of communications for Louis Vuitton, says that former South African President Nelson Mandela tops his casting wish list for the French brand’s Core Values campaign, which trumpets the firm’s travel roots. “It would be a dream come true if one day he accepted to be part of this saga,” he says. Former U.S. President Bill Clinton, whom Louis Vuitton initially envisioned next to Gorbachev in its first spots, is also on the list. According to Arnault, the invitation to do the campaign came after Hillary decided to run for the White House, so he declined it. “We all know that political figures, perhaps more than movie stars these days, are under permanent scrutiny,” Arnault adds. “They are stars in their own way.”

Arnault described an overwhelmingly positive reaction to the Gorbachev spots: Fan mail poured in, and traffic in Louis Vuitton stores increased. “Politics and fashion mingle in dinners, parties, fashion shows,” he says. “Let’s not be hypocritical about it. [Let’s] accept the fact that the two worlds are closer than most people think.”

But for Doonan, that’s a collision he’d rather not witness. “I like my political figures to be frowsy and fashion-free,” he says. “They should be worrying about other stuff while the rest of us are indulging our fashion whims.”

ad: © Louis Vuitton