Rem Koolhaas Is Not a Starchitect

(Just don’t tell his clients that.) Meet the mastermind behind this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale—and the most daring architecture firm on the planet.

Of the many firms headed by a celebrity architect, Rem Koolhaas’s Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) is unique in hiding the light of its famous founder behind an ostentatiously bland label. Even before “starchitect” became a bandied-about term, Koolhaas viewed the phenomenon with suspicion. That didn’t stop him from capitalizing on his reputation and designing some of the most flamboyantly distinctive edifices of this era, including the Beijing headquarters of the CCTV broadcasting company, with its two tilted towers joined at the top and bottom to frame a dramatic void. But even as Koolhaas was riding the wave, he was anticipating the undertow.

When I first met Koolhaas, about 15 years ago, he had just begun to build big. Having made his name as a writer and theorist, with a few small completed commissions, he was borne aloft by the acclaim for Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, which opened in 1997. Suddenly, cultural institutions with substantial budgets were seeking iconic buildings of their own. With a mixture of incredulity and distaste, Koolhaas told me that in 1998 the director of a competition for a new contemporary art museum in Rome said he wanted a building that would do for Rome what the Guggenheim had done for Bilbao—as if Rome needed to be put on the cultural map! (Zaha Hadid, a former student of Koolhaas’s, won the job.)

If you made a flowchart of OMA, which would be a very Rem-like thing to do, you’d find that one of the most striking changes in recent years is that the trajectories no longer all lead to Koolhaas. OMA became less of a one-man show after a former banker entered as managing director in 2005 and restructured the firm. In addition to the headquarters in Rotterdam, Netherlands, OMA has four other offices—in Beijing, Hong Kong, New York, and Doha, Qatar. The staff has grown to 350, with more work than Koolhaas can oversee personally. (OMA currently has projects under way in France, Holland, China, the United Arab Emirates, and Russia.) There are five other partners, whose average age is 45, and while it would be a stretch to say all of them are equal, they each can operate with occasional autonomy.

Of course, there are some clients who might balk at the idea of hiring OMA and not getting Koolhaas, but he is committed to decentralization. Koolhaas turns 70 in November, and rather than slowing down, he is branching out. “If I ever want to do something different from strictly architecture or strictly building, it is really necessary to be in a partnership,” he says. His companion, Petra Blaisse, 59, an interior and landscape designer, says the current setup has allowed a “relaxation” for a man whose springs are tightly wound. “He is not someone who thinks, Okay, I’m done,” she observes. “He wants to keep on learning and developing eternally.”

Koolhaas and Blaisse have been together since 1986—not living together, she notes, “but having a life together.” Three years ago, they began sharing an apartment. Two years later, he obtained a divorce from Madelon Vriesendorp, an artist who is the mother of his two children. On the road constantly, Koolhaas so values displacement and instability both in his life and in his buildings that I was intrigued to find him appearing, in some ways, almost settled. He is a joyously doting grandfather to the 2-year-old son of his daughter, Charlie, 37, who is a photographer. As part of her body of work, Charlie, who lived in China for five years but recently moved to Rotterdam, photographed many of her father’s buildings. Rem’s son, Tomas, 34, a Los Angeles–based filmmaker, also orbits in and out of his forceful father’s gravitational field. He is in the final stages of completing a feature-length documentary titled, simply, Rem. When I spoke to Tomas, he had just returned from a few days of traveling with his father. They started in Doha, going from one meeting to the next, and then went into the desert to do some filming. They spent the night in transit on a series of connecting flights, finally arriving in Venice, where Rem went at once to a meeting and then straight to a press conference. Afterward, they flew to London. While Tomas headed to his mother’s house to collapse, Rem took a car to another meeting. “It’s literally nonstop,” Tomas says. “Not even time to sleep. It was tough for me, and I’m a strong guy. If anything, he’s working harder than he’s ever worked in his life.”

What tickled me most was that Koolhaas now resides in Amsterdam, in a building opposite the Montessori school he attended as a boy. In 2000 he had referred to his childhood city with mild revulsion. Some of his attitude seemed to stem from a Calvinist disapproval of the hedonistic indulgences associated with Amsterdam. But he also sneered at the concentric arrangement of the canals of the city center, which require you to go in circles instead of moving forward. “If you live in Holland, Amsterdam is the place to be,” Koolhaas allows now. “It’s incredibly convenient. I travel so much, there was, maybe, internally a fear that settling here would be tantamount to provincialism. I think I overcame that fear.” As Blaisse describes it, this dread of revisiting the past provides Koolhaas with his motive force. “He got liberated from the fear of going backward, which for Rem is the worst thing,” she says.

In the OMA headquarters in Rotterdam, Koolhaas occupies two perches. The corner office, which is behind transparent glass and is furnished with a large blond-wood table and several chairs, is where he meets with colleagues and clients. This is his public face. Two doors down, smoked glass shields his private office, containing a white metal desk and neat stacks of books. Here he writes. “Writing for him is like composing,” Blaisse says. That is to say, he goes about writing as he approaches architecture, balancing the presentation of ideas with the shaping of spaces. Like the buildings, his books (the most recent, cowritten with the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, charts the achievements of the postwar Metabolist architects of Japan) require some effort on the part of the user. They unfold their surprises gradually.

As part of his branching out, Koolhaas is directing the next Venice Architecture Biennale, which opens June 7. To prepare, he demanded two years instead of the usual six months. He also stipulated that his Biennale would not be a display of contemporary architecture. “They had become more like art biennales, showing famous architects,” he says. Instead, he wanted an occasion for intellectual exploration. Supplying coherence to what is usually a sequence of disjointed spectacles, he is dedicating the vast space of the Arsenale to 41 exhibits. Each jumps off from a particular place in Italy to examine a general theme: hedonism, for instance, as enjoyed in three Capri villas.

When it came to the national pavilions, he asked the organizers to contemplate how their individual cultural styles were (or were not) subsumed by globalism in the past century. In contemplating the erosion of regional architectures, I wondered how Dutch Koolhaas believed himself to be. I associated his longtime fascination with the horizontal plane with the flatness of the Netherlands, as well as with the style of the Amsterdam School of the early 20th century. And I could imagine there was also something Dutch in the way glazing in his buildings more often allows you to see in than to look out. Koolhaas objected to being pigeonholed; he considers himself a hybrid. He spent a formative part of his childhood in Jakarta, where his father, a journalist outspoken in his opposition to colonialism, moved the family during the early years of Indonesian independence. As a young man, Rem studied and taught in the United States and Great Britain. “Originally, I may be Calvinistic with an Asian dimension,” he says. “Then, Anglo-Saxon with a Continental dimension. That gives me some duality.”

If learning is what Koolhaas is actually about, it stands to reason that the Biennale program closest to his heart is the Central Pavilion. Normally farmed out to different architects to devise and underwrite exhibits, the pavilion in this Biennale is under the complete control of OMA. It will be devoted to an exploration of the most basic components of architecture—among them, the ceiling, door, floor, and toilet—throughout history and in different parts of the world. “I realized how incredibly limited my relationship with design is, because I had never considered these elements separately,” Koolhaas says. “You think of them, but always together—the door with the window.” Regarded in isolation, the components take on a different character. A ceiling changes its reason for being, as frescoes are replaced by HVAC systems. “You see the development of the false ceiling, which is ubiquitous now,” Koolhaas says. “You can see clearly how no one uses the ceiling anymore to create an aesthetic or deal with ornamentation, except in a very repressed way.” To manifest that historical transformation, an art nouveau ceiling, recently restored, will be half-covered by a drop ceiling.

Elsewhere in the pavilion, a consideration of the ramp will contrast Claude Parent, a French architect who designed a house in the early ’70s on an incline to throw people off balance, with an American, Tim Nugent, who developed architectural standards for handicapped access. “It shows how boring we’ve become,” Koolhaas says wryly.

Koolhaas’s early career ambition was to be a screenwriter, and upon entering his architecture, one feels like a player in a scripted performance. OMA’s two most recent Dutch projects extend the cinematic sense to a dolly-cam shot of the exteriors. Rather than design buildings as sculptures, to be regarded from different stationary sight lines, OMA reasoned that the most frequent view of these structures would be in motion, from the window of a car. The three towers of De Rotterdam, which opened late last year and make up Holland’s largest building, seem to project forward as you ride across the Erasmus Bridge into Rotterdam’s redeveloping wharf district. As the view changes, the towers—a hotel, office blocks, and a residential building, rising from a shared six-story plinth—separate and then merge. The other project, in an industrial district by the ring road that surrounds Amsterdam, is showier—appropriately so, because it serves as the headquarters for G-Star RAW, a Dutch fashion company. When you drive past it, especially at night, a cantilevered glass box containing the showrooms in this glass-and-steel complex juts out prominently and glows with a dramatic light.

Still, the G-Star building seems relatively tame compared with some of OMA’s projects in Asia and the Middle East, where flashy architecture is very much in demand. In Qatar, OMA is designing three buildings for an “education city,” including a determinedly iconic library, in which the floor plate tilts upward from each side of the entry to create an enormous open interior; in Taipei, an under-construction concert hall consolidates the technical facilities for three auditoriums within a translucent central core, from which the public spaces bud out with geometric boldness—a sphere, a rectangular box, a trapezoidal solid. As publicly assertive as the Asian projects are, the recent European ones are discreet. In the densely built business district of London, OMA slipped a headquarters for the Rothschild firm into a narrow street that has been home to the family’s banking operations since the 19th century, providing a view of a Christopher Wren church that the previous building blocked. In Bordeaux, France, OMA won a competition to construct a bridge. Flat and straight as a ruler, this radically unexpressive bridge has more room for pedestrians than cars. When closed to traffic, it can be used for fairs and festivals.

Even more self-abnegating is an OMA project in Moscow, a city awash in oligarchic bling. In Gorky Park, one of the oligarchs, Roman Abramovich, bought a crumbling Soviet-era restaurant for his culturally ambitious girlfriend, Dasha Zhukova, to transform into an art gallery. The Garage Museum of Contemporary Art will be housed in the ’60s concrete prefab structure, which was abandoned after the collapse of the Soviet Union. OMA is sheathing the building in two layers of translucent polycarbonate and placing the mechanical, electrical, and plumbing conduits in between. Otherwise, the Garage Museum is an exercise in preservation. At first, that might seem uncharacteristic, because Koolhaas views the current historic-preservation craze with a jaundiced eye. “Twelve percent of the entire world’s surface is under some kind of preservation,” he remarks. “The world is in a strange position of radical change and enforced stasis.” This is a subject that has been plumbed by AMO, the research arm of OMA that Koolhaas founded in 1999. He says that the movement really got going during the French Revolution—“a counterpart to radical change”—and, ever since, has extended its protective shield over the more and more recent past. He carps that a residence he designed in Bordeaux was declared a protected monument soon after it was finished, in 1998.

“In this wave of preservation, there is one exception—that every building from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s should be destroyed,” Koolhaas says. He argues that the reason is not because the buildings of the period are ugly and anti-humanistic but, rather, because “they are all ideological—it was the last time there was civic municipal architecture.” The more despised and overlooked a genre, the more affection Koolhaas feels for it, so, of course, he has a soft spot for Soviet architecture, especially in its full-blown brutalist and doctrinal form. When I wondered whether, to gild the lily, OMA would be preserving the graffiti emblazoned on the Garage building during its derelict years, John Paul Pacelli, a young architect on the project, informed me, “We considered keeping it, until we found out a lot of it is hateful.” I mention this to Koolhaas. “Yeah,” he says, “but we preserved some.”

OMA’s most intricate game of preservation and intervention is being played out at the Fondazione Prada, an exhibition space in an industrial site south of Milan and due to open in 2015. OMA has been working with Prada for 15 years, on everything from fashion shows to store design. Although Miuccia Prada’s original concept for the Fondazione was to create different centers globally, her husband, Patrizio Bertelli, argued that it should be based in Milan, where the company began. Since they already owned a century-old defunct distillery complex, they asked Koolhaas if he would create a museum on that site. “He didn’t like the idea, because the industrial transformed into a museum is not a new idea,” Prada says. “My husband said, ‘If you want to raze everything, you can do it.’ ” But she demurred. “It looks like a little village. For me, even if it is not the newest idea possible, it is still good.”

Koolhaas eventually decided to demolish two structures that were judged to be without aesthetic merit and introduce three bold new buildings: a low, horizontal one with an aluminum foam skin; a concrete and glass tower; and a performance space with a polished-aluminum facade. The horizontal building, with rigorously controlled lighting and climate, can be used to display loaned art. In the tower, select works from the Fondazione will be on view. The old warehouses, offices, and vaults are to be used for all kinds of contemporary art, including performances and installations. “I think the combination of new and old is very good—sometimes violent, sometimes not,” Prada says. Her intention is for the Fondazione to mount exhibitions on a theme that will be explored consistently in the different spaces (a notion similar to Koolhaas’s concept for the Venice Architecture Biennale). She wants to knock art off its pedestal and to dispel its sacred aura. “I am not obsessed with art but with ideas,” she says, almost echoing Koolhaas. “The architecture is invasive. Art that is too protected, I don’t like. I want art that loses its position. I want art to become more political, more real, more dirty in a way—ready to solve our problems, more practical than religious.” The tension of the architecture is meant to create friction, and the sparks, she hopes, will generate ideas.

Despite receiving all the honors and recognition that his profession can award, Koolhaas still struggles. He thrives on struggle. He estimates that one-third of the firm’s work derives from competitions, and OMA wins only one out of every three or four it enters.

Often, he is vying with younger architects he once employed. Recently, for a coveted commission to build a headquarters for the Axel Springer media company on a site that was part of the Berlin Wall, OMA bested Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and Büro Ole Scheeren, both headed by former OMA architects. Last year, OMA triumphed over BIG in another contest, this one to design the Miami Beach Convention Center. (Illustrating the vagaries that bedevil architects, in January a newly elected mayor killed the OMA project.) Koolhaas seems to accept the Oedipal aspect of these conflicts with his former protégés. “It’s the natural order of things, so I don’t have a trauma with it,” he says. What irks him is the suggestion that a stint at OMA transforms an architect into a newly hatched Rem. “There is an assumption that there is a similarity of thinking,” he says. “For me, privately, the most pronounced difference is a wider cultural-political vision and a more precise anticipation of what the important issues are going to be. I am more interested in participating in moments of significant change—and in taking bigger risks.”

The attraction to creative discomfort—the preference for Parent’s tilt over Nugent’s ramp—is central to Koolhaas’s thinking. “He has an issue with comfort and the desire of people for comfort,” his son, Tomas, says. “He thinks it’s the antithesis of ambition.” Tomas and Charlie chose to attend state schools in Tufnell Park, on the border between Islington and Camden, in North London. “We could have gone to private school, but we went there,” Tomas remarks. “That’s in line with Rem’s idea of not being too comfortable.”

Indeed, as extravagant as some of his buildings may appear, Koolhaas prizes frugality. From the beginning of his career, he has worked in cheap plastic, along with exotic wood. And when he indulges himself personally, he keeps his consumption as inconspicuous as possible. “I am very lucky to be part of a generation that has experienced poverty,” he says. “We moved to Amsterdam, which was devastated by the war. My parents were absolutely poor—with bicycles with wooden wheels. The idea of luxury was extremely remote and has remained remote. I have pleasures, like swimming, that are often quite cheap.” I couldn’t resist mentioning his penchant for fast cars; he is currently driving a BMW 850, which is not exactly a Hyundai. “Yes, but I got it on the Internet,” he retorts.

Every other month, he and Blaisse try to spend a few days on a remote Italian Mediterranean island, in a little stone house that is essentially one room with a fireplace, a bed, and a kitchen. Koolhaas finished restoring the cottage four years ago, but, constrained by strict rules on development, he could not expand its minuscule size of 300 square feet. The house lacks telephone and Internet. The couple luxuriate on a terrace with a commanding vista of the sea. Koolhaas swims year-round. Although the house is difficult to reach, he doesn’t mind. “With every step, you get further away from everything,” he remarks. Blaisse corroborates that, on the journey to get there, “you see him as if you peel an onion. Finally, you are on the ferry, and that is it—it makes him extremely happy.” No one can pester him there. To receive an e-mail, he has to go into town; if he wants to make a call on his cell phone, he must climb a hill and hope for reception. For a cerebral man, this is a very romantic place to escape. Looking at it in psychological terms, you might say that, for Koolhaas, it represents a step forward.

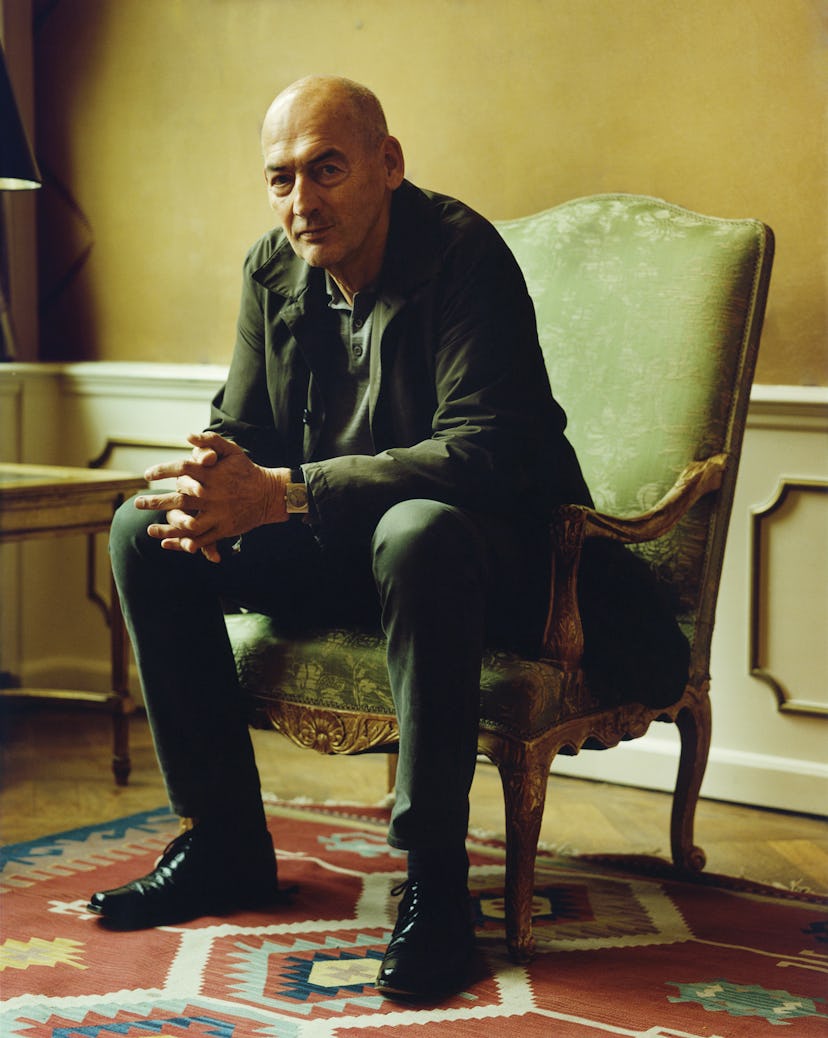

Photos: Rem Koolhaas Is Not a Starchitect

The architect Rem Koolhaas in the Ambassade Hotel in Amsterdam. When he is in town, the hotel serves as a makeshift office.

Phase-one model of a project in Nanterre, France.

The dome of the model for the Central Pavilion of the Venice Biennale.

Rendering for the Fondazione Prada in Milan, which is due to open next year. Image courtesy of OMA.

A model for the Fondazione Prada in Milan, which is due to open next year. Image courtesy of OMA.

A model of the Fondazione Prada in Milan, which is due to open next year.

De Rotterdam completed. Image courtesy of OMA; photography by Ossip van Duivenbode.

Models for Der Rotterdam, the largest building in the Netherlands. Image courtesy of OMA.

Rendering for Pont Jean-Jacques Bosc in Bordeaux, France. Image courtesy of OMA.