Sterling Ruby: Balancing Act

The artist Sterling Ruby’s bright future appears momentarily in doubt as he turns left off 26th Street in an industrial sector of downtown Los Angeles and suddenly faces a tractor-trailer, its white cab aglitter with chrome and menace. A split-second later, it’s clear that there’s no real danger—the truck is slowing to make a wide right turn—but the approaching hulk still appears ominous from the lower perspective of Ruby’s front seat. Its headlights are fierce eyes, the massive grille a toothy maw, and the manufacturer’s name, approaching us at eye level, is declared in manly block letters: sterling. “I was almost taken out by Sterling,” notes the 42-year-old with daredevil glee.

In a decade that has seen Ruby become the dominant L.A. artist of his generation and a star on this year’s international biennial circuit, he has faced actual perils that might have flattened a less ambitious man. In 2005, he failed to receive his master’s degree from Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. While his advisory committee supported the merit of his final project, which included a weird video triptych that showed the artist in flagrante with a skull—a shaky reference both to Shakespeare and to perhaps more senior local artists like Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley, Ruby neglected to turn in his thesis. Three years later, Ruby survived the bust-up of his first studio, a collective space in one of Los Angeles’s gangland neighborhoods. And, more recently, he weathered the charge of being a careerist gallery hopper after he moved in quick succession from L.A. based Marc Foxx to Manhattan’s relatively low-key Metro Pictures to the more internationally known Pace Gallery to the global powerhouse Hauser & Wirth.

But none of those threats to Ruby’s reputation as a serious artist have imperiled his ability to make money. Like a punk rocker who breaks into the Top 40, Ruby has surged to market heights, thanks largely to support from supercollectors including Michael Ovitz, who set up a meeting with Pace when Ruby decided to leave Metro Pictures.

“ ‘Material’ ** is the word that comes to mind when I think of Sterling’s work,” says the artist Alex Israel, a 31-year-old native Angeleno. “I remember thinking the first time I saw one of his ceramic pieces that no one was doing ceramics and yet he made it seem relevant and gorgeous and really fresh. And his stalagmites are these strong totemic sculptures that appear malleable and liquid. He’s inventing new forms that are somehow both alien and familiar—that feel like they are tapping into the pulse of our time. Sterling’s work doesn’t look like anyone else’s.”

And yet, until recently, his rise has not been universally cheered by critics. “Sterling has such a drive to produce, and he wound up being very commercially viable, very early on,” says Philip Tinari, director of the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, which will feature Ruby as one of eight artists in “The Los Angeles Project,” an exhibition opening in September. “For those of us in the critical establishment, that kind of success usually creates a disinclination to like the work. Artists who are able to build a giant apparatus marginalize themselves by being too successful, unless it becomes part of their shtick, like with Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst. But Sterling is sincere.”

And as for the observers who fret about Ruby’s equally sincere commitment to sales—well, time is on his side. A generation of young curators including Tinari, who is in his mid-30s, came of age in the era of superstar artists like Hirst and are less inclined to look down on business savvy. These new arbiters are the ones who have booked up Ruby’s exhibition schedule. This year alone, his signature clay “basins”—which look like oversize ashtrays drenched with wet-finish glazes and filled with the fragments of earlier pieces—were included in the Whitney Biennial, and the Baltimore Museum of Art recently opened a show of “soft work”: fabric sculptures of what Ruby calls “vampire mouths.” (“My Rolling Stones tongue,” he jokes.) Ruby unveils new works in May at Hauser & Wirth, New York; in September at Taka Ishii Gallery in Tokyo; and he will also be represented at the Gwangju and Taipei biennials, which open at the same time as the Ullens Center exhibition in Beijing. He calls the run of transpacific dates his “Asian tour.”

Ruby’s booming career is reflected in the spaces that have given rise to it. When I first saw his current studio on 26th Street some five years ago, he and his 10 assistants had just moved in, and the place seemed gigantic. The converted industrial space consists of a series of workshops, each dedicated to one of the many materials Ruby uses in his versatile practice. One is for drawing; another for ceramics (the basins are made with up to 300 pounds of clay); another for ceiling-high poured-urethane sculptures (his instantly recognizable “stalagmites”); another for fabric collages; another for paintings (up to 20 feet wide); and, finally, a white-walled gallery to display completed works. The really big pieces are assembled outside: The cardboard-and-urethane forms used to cast his stove sculptures require a forklift to transport them around the studio. After my first tour, I walked away unsure of how to characterize him as an artist (sculptor? ceramist? painter?) but with a clear understanding that everything about Ruby’s practice, apart from his own compact physical stature, was XXL.

Now, five years later, Ruby and his current team of 14 assistants have outgrown 26th Street, and he’s building a new studio nearby that dwarfs the old one. The compound encompasses four acres—more than two acres are under roofs. When you set foot inside the main building, the feeling you have is something like awe. Its central bow-truss ceiling soars to 42 feet and is flanked by barrel vaults on either side. Thirty thousand square feet will be devoted to a viewing room where Ruby can study his work—a mega-gallery of his own. A separate building houses a ceramics studio with glass-fronted bays large enough to park in. Another 10,000-square-foot corrugated-metal building is reserved for storage, so that Ruby can hold back 50 percent of his production as a personal archive. On the bright spring day when Ruby shows me around, it is months before he will begin moving in, and only one artwork has been installed. It is, predictably, large. The cast-bronze basin is a Pompeian riff on his ceramics, he says, and it could easily serve as a wading pool for Ruby as well as his wife, the artist Melanie Schiff, and their children were it not tipped up as a wall sculpture and filled with quasi-archeological scrap from the foundry in China that fabricated it. If Ruby’s current studio is XXL, this new one will be XXXXL.

Born in 1972 to a Dutch mother and an American father in Bitburg, Germany, Ruby and his family lived for a time in Baltimore before moving to rural Pennsylvania, the childhood home with which he most strongly identifies. By 13, he was focused on the California punk scene and busy with a sewing machine that his mother had given him; his peers preferred shop class. Ruby got into a lot of fights. He still sews, and in addition to his fabric sculptures, he makes fabric-collage “paintings” that reference the Pennsylvania quilting tradition; he even designed his own studio wardrobe of denim trucker jackets, jeans, and aprons—all splattered with paint and drips of urethane. Ruby’s attire intrigued the fashion designer Raf Simons, the creative director at Christian Dior, who has collected Ruby’s work in depth and referenced it in his designs since they became acquainted nearly a decade ago. At Simons’s prompting, the two designed a collection for Simons’s eponymous men’s wear label; it was shown in Paris this past January, vampire-mouth fabric sculptures looming over the runway. “When we worked together, it was almost like being married,” Simons recalls of the collaboration, noting that his family in Belgium lives just across the border from Ruby’s Dutch relatives—a bond they discovered when they first met. “The collection grew out of years of talking—so many similarities between us, so many shared interests. It was a really natural thing to do.” Ruby likens the experience to the Bauhaus practice of combining craft and fine art, and says he loved the standing ovation that ended the show. “Raf was crying, and I was crying,” Ruby recalls with a laugh. “Everybody was standing up, cheering. At that moment I thought, Fuck being an artist—this is wonderful.”

Ruby realizes that some may look askance at his fashion-world dalliance, but he prefers not to distinguish between his side projects and his so-called serious work, because he views what he does as a single practice that challenges old artistic hierarchies that place metal and paint (“masculine”) above ceramics and fabric (“feminine”). Former Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA) chief curator Paul Schimmel, who is now a partner in Hauser & Wirth’s upcoming L.A. gallery, suggests that Ruby’s dislike of such judgments stems from his view of himself as an art world outsider, someone who grew up far from the “thin sliver of culture” along America’s coasts. “It’s almost a moral stance for him,” Schimmel says. “It’s fundamental to how he sees himself.”

After his undergraduate years at a small Pennsylvania art college that emphasized unfashionable craftsmanship courses and sketching live nudes, Ruby earned a BFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Then he headed west in 2002 to attend Art Center, attracted by what he calls the “pathology” of Los Angeles and the presence of established artists including Kelley, who was then an Art Center faculty member; Chris Burden; and Paul McCarthy. “It was a completely different art world than New York,” Ruby explains one morning at the pleasant but modest house he and Schiff own in Sunland, about 45 minutes from downtown L.A. “It seemed way more dangerous. I was drawn to that.”

Apparently, the sketchy fringe still appeals. The suburb used to be a Hells Angels hideout. “Some of the neighbors were unsure about having a couple of artists move in,” Ruby says as he shows me around the acre plot and his contemporary house—painted matte black—shaded by oaks. But over time, the Ruby-Schiff clan has quietly fit in. “It reminds me of where I’m from. Sort of rural. We have a Sizzler.”

Since arriving in California, Ruby has consistently explored antisocial behavior and his own relationship to art history. He assisted Kelley as a grad student, and from their conversations, he developed the notion of the artist as criminal, someone who decontextualizes meaning and faith with only a skewed sense of social responsibility. Ruby’s key themes were fully expressed in his breakout solo museum exhibition, “Supermax 2008,” at MOCA, which drew parallels between the penal system and art history, the common thread being incarceration and repression. It amounted to a forceful reaction against the theory-heavy curriculum at Art Center, where, in Ruby’s opinion, discussion was given precedence over studio time. Almost as revenge against the faculty, Ruby stuffed as many handmade objects as possible into the galleries. The exhibition included sculptures, paintings, drawings, and collages, all of which shifted abruptly between the anthropomorphic (goopy, drippy, wet) and the geometric. “It had to be packed, dense, confusing,” Ruby explains. “It had to be nauseating.” Some of the hard-edged sculptures were purposely defaced with dirty smudges and graffiti, as if Ruby were “tagging” the pristine legacy of his minimalist and conceptualist forebears. Some visitors walked away saying “This guy needs to figure out what he wants to do,” Ruby recalls. Ovitz and his curator, Nu Nguyen, were not among them. “I was blown away that he could work in so many materials and deliver a message as coherent as it was,” Ovitz says. “We sat in there for about an hour, and when we got in the car, we called his studio to start talking to him about doing something for us.”

Ruby had produced the “Supermax 2008” work at the studio he shared with a revolving cast of 10 to 15 other young artists—including Amanda Ross-Ho, Brenna Youngblood, and Aaron Curry—in the aptly named Hazard Park neighborhood. Their dilapidated sheet-metal building once partially collapsed during a minor earthquake; another day, a shoot-out took place on their street. Ruby and his studio-mates were energized by the gritty reality of making art among the gangbangers: It felt dangerous and, thus, somehow authentic. “I think in many ways the best part of being there was that we were working toward a movement,” he recalls. “We fed off one another.” But the group fragmented only three years after it was formed. Feeling hemmed in by the emotional complications of navigating friendship, studio life, and gallery politics, Ruby left in 2008. He skirts the details of the studio’s breakup, other than to say, “It was a pretty conscious effort to drop out.”

Today, Ruby keeps an orderly 9-to-5, Monday-through-Friday work schedule. He insists that his real job is making stuff, and he goes to work like a blue-collar man. He -acknowledges that he’s not entirely comfortable with the established gallery system—“Very early on, I started to think about what it is to share 50 percent of your income with a dealer,” he says—and he cites Kelley and Burden as other artists with working-class roots who taught him to be pragmatic about money. “I have to say that I can’t do this without the dealers,” he tells me on another day. “But I think that at some point in the future, they will have less of an impact on the market, and artists will do things differently.”

Nine years out of grad school, Ruby oversees a studio humming with activity and is making the transition from “young” to “midcareer” artist. When I show up at the studio a week after our meeting in Sunland, Ruby emerges like an apparition in a paint-splattered white-denim outfit that looks as if it had doubled as a drop cloth. He jokingly calls it “studio camo.” Sitting down, he tells me a story he apparently forgets having told me the week before. Ruby recently ran into the artist Diana Thater, whom he knew as a grad student at Art Center but hadn’t seen for years, and certainly not since she became chair of its Graduate Art department. “The first thing she said was, ‘Sterling, I’m the chair. I can get you your degree now,’ ” he recalls. At first, he wasn’t sure whether he wanted to sew up this small rip in his legitimacy, but then he told his studio assistants to dig into his digital archives for a copy of his forgotten thesis and video project to send Thater. The degree would be purely symbolic at this point, but apparently old scars still smart. “I figured I paid for it,” Ruby says. “I should probably have it.”

Photos: Sterling Ruby: Balancing Act

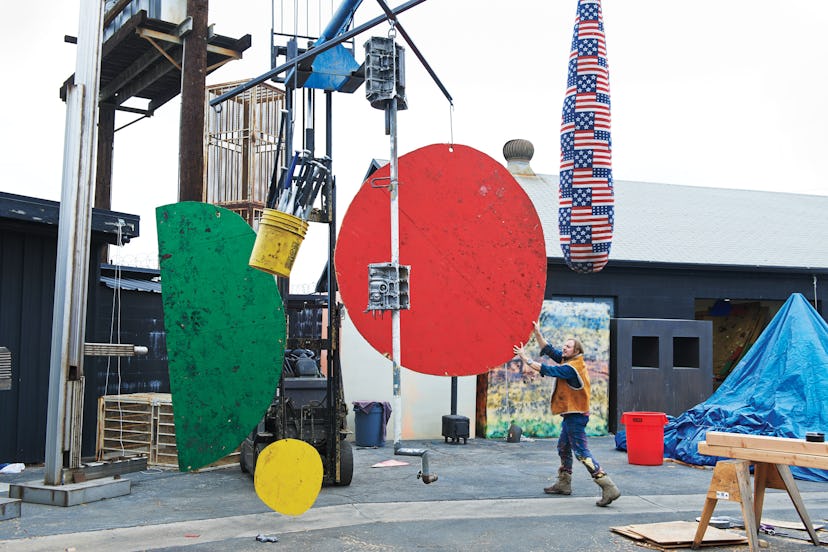

Ruby, outside his studio, with Scale (4837), 2014.

Ruby’s ceramics studio.

A ceramic work in progress.

The artist in his textiles studio wearing a fall 2014 Raf Simons / Sterling Ruby jacket, with diptychs BC (4844) and BC (4845), both 2014, behind him.

Another work in progress.

Textiles for BC Collage Series, quilts, and soft sculptures in Ruby’s studio.

A work in progress.

Ruby’s home in Los Angeles, designed by Anonymous.

Pillars, 2014.