Five Minutes with Takashi Murakami

Has it really been five years since Takashi Murakami put on a show in the U.S.? In a new exhibition, the artist confronts self-examination and mortality.

Has it really been five years since Takashi Murakami put on a show in the U.S.? In 2008, his major retrospective, ©Murakami, at both the Brooklyn Museum and MOCA, Los Angeles, established the Japanese artist as a juggernaut in the Warholian mode, who along with contemporaries Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, straddles the line between art and commerce. But when the economy fell off a cliff, so did the fashion for unselfconsciously commercial art. For Murakami, change came in the wake of the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear plant meltdown that struck Japan in March, 2011. Arhat, his new solo exhibition of paintings and sculptures at Blum & Poe gallery in L.A, which opened on Saturday, refers to the original disciples of Buddha who have the ability to alleviate human suffering. The artist began the new work immediately following the troika of disasters. “I felt it was necessary to have religion in my work,” he says. While his style is still rooted in colorful manga and nihonga painting, his themes have turned away from capitalist culture towards the contemplation of a more interior life. In this show, he confronts self-examination and mortality.

Another breakthrough comes in the form of Murakami’s first feature film Jellyfish Eyes, a live-action monster movie with animation meant for children, which screened at LACMA last week. The coming-of-age adventure centers on a boy who moves to a new town after losing his father in the 3/11 disasters. Having a hard time fitting in, he befriends a marshmallow-like jellyfish. It’s another form of art therapy.

Your last show in the U.S. was in 2008. Did having such a widely-viewed retrospective push you to develop artistically in new ways? ©Murakami changed the trajectory of my career. Up until that point, the standard view was that I was an artist influenced by Japanese subculture, especially manga. But thanks to the work of curators Paul Schimmel and Mika Yoshitake, people began to view my art as being firmly rooted in art history, and strong enough to survive into the future.

My more recent work, especially in the aftermath of the March 2011 earthquakes and tsunamis in Japan, has moved in a different direction. Before, I had been exploring the relationship between capitalism and art. But in the face of such catastrophe and the wounds that resulted from it, I realized that if I continued only trying to make art from within the context of our man-made society, there would be no message in that work for the disaster victims. I had to create something that could help mend human hearts, even if my art is merely a placebo. The themes in my work began to change: For my exhibition Murakami—Ego last year in Doha, I unveiled a 300-foot painting called The 500 Arhats in which I attempted to capture the human sadness that comes with having to stand by and watch as unfortunate events unfold.

You’ve also made yourself the subject of your work over recent years. Before I became an artist, I discovered the drawings of the German printmaker Horst Janssen while I was studying for college entrance exams. His pieces were such a shock to me that I began making studies of them on my own. Most of his works resembled eroticized versions of Egon Schiele portraits, with the artist depicting his own aging body. For me, they seemed in quite bad taste, but that was precisely what made them so powerful. It was the first moment that I really asked myself, “Is this art?” After that, I felt a connection to self-portraits; I decided that once I mastered the rules of contemporary art, I would create some of my own. I hope to continue exploring self-portraits in the future and to venture further into the realms of bad taste.

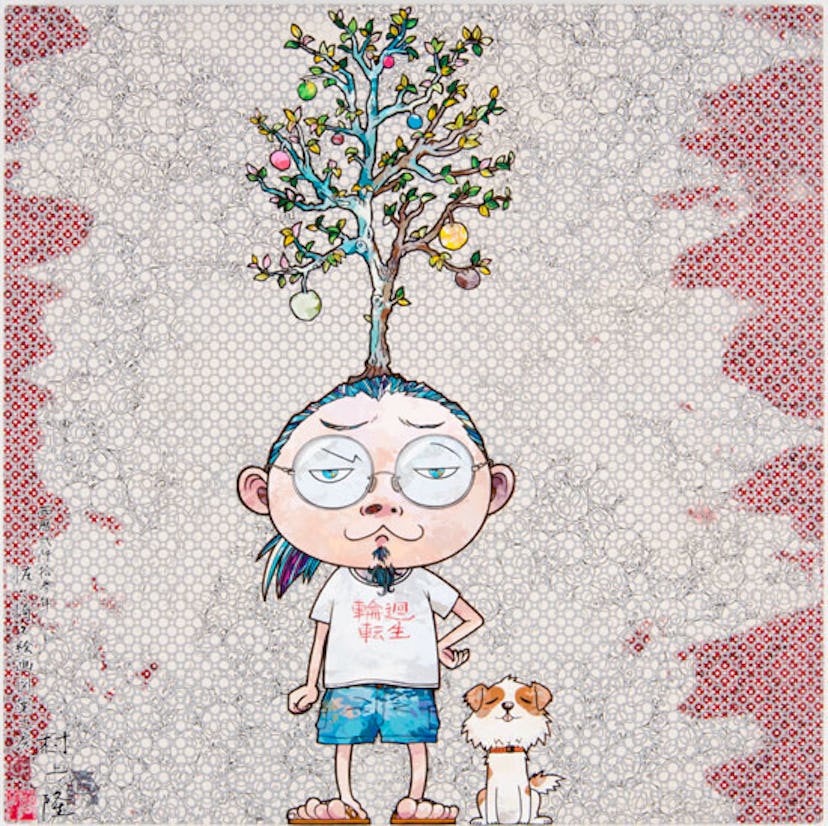

Your dog Pom, whom you found at a hotel in Japan, has also been incorporated into your work. Do you have a strong emotional attachment to animals? I don’t fully understand it myself. But before I began keeping Pom, I had never had any pets capable of expressing emotion. The most biologically advanced pet I had was a turtle, but other than that there were fish, insects, and hermit crabs. The reason was because with emotion, there comes companionship—and with that, the fear of losing that companion. Now, however, I am forced to contemplate the possibility of my own death and have come to terms with it enough that I am also able to face up to the thought of having a companion for only a limited amount of time. Thus, I now have a dog.

Speaking of death, it’s become a feature of your recent work. We see that in this show with the sculpture of a gold-plated skull engulfed in flames. What’s your relationship to mortality? I’ve been afraid of death since I was a child—not so much death itself but the pain and suffering that accompany it. For that reason, I’ve never been able to watch horror movies. I know that every fall, there are a ton of horror movies released but I can’t for the life of me understand what it is that people find enjoyable about them.

The trailer for Murakami’s Jellyfish Eyes

You’ve just made your first feature film, which you’ve been working on in some ways for a decade. What was the inspiration to make a film? Ten years ago, I had planned to make Jellyfish Eyes as an animated film. In the end, it turned into a live-action film, but in my mind it’s still half-cartoon. It’s intended to be a message to the Japanese children. Today, there are many kids in my country who are told by adults that they will grow up to achieve their dreams and live a life without hardship. However, when they actually do get older, they see the frailties of adult behavior, grow sick to their stomachs, cut their ties to society, and retreat into a world of their own. This problem is especially relevant in the aftermath of 3/11. I want these children to have a firm view of reality, and to grow up stronger. I felt that this message would come across easier if wrapped in the package of a fantasy film.

Images: Pom & Me: Sprouting a Tree from My Head: Acrylic on canvas mounted on board 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 centimeters) ©2013 Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Image courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles. Flame of Desire – Gold: Height: 187 inches (475 centimeters) ©2013 Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Image courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles Edition of 3, 2AP.