The Response to Trump in China: Among Its Cultural Elite, “Meh.”

A week amid the what-me-worry billionaires in Shanghai, as America fell into shock and dismay.

Last week, I was in Shanghai watching a live parrot chained to a television screen when Donald Trump won Ohio. The parrot was part of an art installation by the Chinese artist Yang Zhenzhong called “If You Have a Parrot, What Words Would You Teach Him [Her]?” The TV beneath it played a video depicting mouths force-feeding the bird new words. But the bird remained silent.

And then Pennsylvania looked like it would fall. On Twitter — blocked in China, of course, without a VPN — the squawking had already begun.

The West Bund, where I stood in front of this 2001 work in the ShanghART gallery, is Shanghai’s newest gallery district, an art mecca fashioned in just two years’ time by the local government — an insta-Chelsea, essentially. In Shanghai, the interests of the intellectual elite and government-sponsored real estate tycoons are not only not in opposition, the two parties collude openly. The local government offers up spaces to preferential tenants: Down the road is the Long Museum, belonging to one of China’s richest men, Liu Yiqian, and his wife Wang Wei; practically next door is Qiao Space, domain of the karaoke nightclub king Qiao Zhibing; and a few blocks away is poultry magnate Budi Tek’s Yuz Museum. ShanghART, the city’s premier gallery, is joined now by temporary exhibition spaces and the three-year-old West Bund Art and Design fairgrounds. Nearby, acres of luxury condos are under construction, with come-hither names like “Only Riverside Art Noble Global Elite.”

Across the way from ShanghART, the West Bund Art and Design fair was having its first official day in business, but rather than the the frenzy of buying and selling, dealers nervously checked on the U.S. election. London’s Timothy Taylor Gallery’s director of exhibitions Tania Doropoulos ran up to her colleagues: “It’s changing every 30 seconds!” she cried. Between Brexit and Trump’s probable victory, she said to me, “We have the world’s two stupidest countries.”

“Today, nobody is talking about art,” the eminent Shanghai gallerist Pearl Lam railed at her booth. “I’m shocked. I’m shocked! He’s a symbol of the downfall of America,” she said, half-yelling in a black fur-trimmed coat. “Clearly there is a big problem with American education.”

“You can’t screw up an election here,” added her gallery director Nick Buckley-Wood, slyly.

I passed the Hong Kong–based artist Enoch Cheng in the halls of the fair. “It’s the end of world,” he said.

A few blocks away at his own Yuz Museum, Budi Tek was preparing for a gala dinner for his foundation. Surrounded by his new acquisitions of the work of American artists like Samara Golden, Ian Cheng, and Mira Dancy, the Chinese-Indonesian mogul looked unfazed by the impending Trump result. “For me, I have no burden. But I think Trump is good. I predicted Trump,” he said. “We already know Clinton is not good. We do not know yet if Trump is good. Give him a 50-50 chance! You have separation of powers”— hardly a given in China, of course — “why do you have to worry?”

Moments after the election was officially called, a preview tour of the Shanghai Biennale was underway at the Power Station of Art, attended by K11 Foundation’s Adrian Cheng and MoMA PS1’s Klaus Biesenbach. Cheng, the collector whose newly forged interests in American institutions — like his trusteeship at PS1 and his efforts to promote Chinese contemporary art with the New Museum — was quiet on the subject. Biesenbach brought up his application for American citizenship: “I’m in the process, but maybe I’ll cancel it.”

The tour continued. The Chinese media had already begun churning out articles and notices about the government’s willingness to work together with the president-elect, but the state-sponsored line rarely acknowledged any concerns about Trump’s aggressively negative rhetoric towards China during his campaign. Articles in the official Communist party-run newspaper Global Times ran the gamut from predictions of a stronger, more forceful China in the international power hierarchy, to an article with the headline “Trump Won?!”

The day before, on what was actually November 8 in Shanghai, Cheng’s K11 celebrated the opening of “Hack Space,” a reimagining of the artist Simon Denny’s 2015 Serpentine Gallery exhibition with contemporary Chinese artists, as well as solo shows by Neil Beloufa and Guan Xiao. Even then, under the presumption of a Hillary Clinton victory, the conversation that day still favored a future in which China, and the cultural might of Shanghai, grows ever more dominant on the world stage.

“Look at K11 — it’s not happening in the West,” Cheng boasted of his exhibition model, which involves showing high-caliber art in his luxury shopping complexes. “China will create its own idea of what a museum is, not denominated from the Western perspective. Everything in China is fresh. It’s like a white piece of paper.”

The work of Chinese artists in the show, such as aajiao, Lin Ke, and Cui Jie, also addresses the concept of “shanzhai”— the Chinese proliferation of cheap imitations, primarily in the form of electronics and luxury goods. The curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist, who collaborated on the exhibition and has been coming to China for more than 20 years, reaffirmed that Shanghai is at the peak of its powers. “It has very clearly shifted. This is the capital of exhibitions in China,” he said. “It’s glocal in the true sense of the word.”

Simon Denny, whose art was on display, was a little more literal: This was an exhibition in a mall. “Obviously it’s not a typical white-space exhibition,” he said. “There’s these posters of my work all throughout the building among branded material.”

That same night, Biesenbach and Chinese collectors threw an affair, which they dubbed a “Serious Adult Dance Party,” at the Shelter, Shanghai’s infamous club in a former bomb shelter that will close in 2017 at the behest of the Chinese military. The irony of the day’s events wasn’t lost on Denny: “The U.S. might elect a billionaire president tomorrow.”

And it did. The evening of November 9 in China time, exhibition openings, gallery dinners, and parties went forward as planned. Qiao Zhibing threw a blowout party at his Shanghai Night karaoke club to celebrate the opening of an exhibition by Martin Creed at his newish Qiao Space. Throughout the club, girls in beauty-pageant dresses waited in holding areas or tore briskly across the marble floors through gilded hallways into private karoake lounges as electronic music reverberated around the walls. It was hard not to think of a certain short-fingered American who owns both entertainment complexes and beauty pageants.

On November 10, the morning after the U.S. election in Shanghai, the Art 021 fair opened. The fair is now held at the Shanghai Exhibition Center, a neoclassical candy corn-shaped building lit up like a karaoke club; it’s part of the former residence of the turn-of-the-century billionaire Silas Aaron Hardoon, a flamboyant real-estate magnate whose fortune was confiscated by the government after his death. The building later became site of the first conference of Shanghai’s Communist Party of China, before it was rechristened the Sino-Soviet Friendship Building, and finally rebranded as the Exhibition Center.

“The party still goes on,” the gallerist Simon Wang summed up at his Antenna Space booth. “People here really don’t care [about U.S. elections]. We don’t even get to vote for a president. We just wait for the arrangements.”

“Still,” he added, “it’s surprising.”

Mathieu Borysevicz of Shanghai’s BANK Gallery, who has lived in China since the 90’s, said, “In the art world we’re knee deep in capitalism, and it’s like: Now what?”

“I think people think it’ll be fun. It’ll be interesting,” said David Tung of Lisson gallery, who is based in Shanghai. “People in general are tired of political correctness.”

But many expats were still in shock, largely because the pundits had all been so far off. “It’s kind of terrifying to think we live in a bubble,” said Philip Tinari, director of the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art. He voted absentee in Pennsylvania, and not for Trump. He added, “I think people here are annoyed by the fact that we care so much.”

At the Hong Kong-based de Sarthe Gallery, Willem Molesworth, an American, was surprised at the normalcy. “I was worried about sales,” he said. “But everyone is like, ‘No one cares here.’”

What one would have thought would be the explosive topics of the day — trade wars, animosity over China’s rise, Trump’s promises of returning manufacturing to America — hardly came up at all. Though the Shanghai art world’s perch may be high above the fray, few there seemed genuinely worried about America under Trump.

On Friday, the Shanghai Biennale opened, curated by the New Delhi-based artists of Raqs Media Collective, and showed a group of mostly Chinese as well as Indian artists in the giant former factory space.

There, Chris Reynolds of INK Studios, a gallerist who lives between Beijing and New York, took note of the nonresponse. “People aren’t very disturbed. It’s sort of ‘sign of the times,’” he said. “There’s just another strongman around — Putin, Xu Jinping, and now Trump.”

“I’ve heard a lot of pro-Trumps,” said Billy Tang of Beijing’s Magician Space gallery. “People think it’s something new and different, disrupting the status quo — even though the policies he proposes are completely harmful.”

“The world is changing,” Sabih Ahmed, part of the Biennale curatorial team, said in his opening statements at the gala dinner. He invoked the title of the Biennale: “We have to ask ourselves the most fundamental questions again.” Across from me, the Beijing-based artist Han Bing, whose work is featured in the Biennale, summed it up less diplomatically: “I don’t like Trump,” he said, adding, “I think Chinese think a lot of American people must be stupid.”

From there, Art Week in Shanghai sparkled on without incident — not least of all because protests are banned and debate about identity politics is all but completely censored in China. BANK inaugurated its new space, after being forced out of its previous one by the government. “Chinese don’t really flinch at this kind of thing,” the curator Victor Wang, who lives between London and Shanghai, said of the election. (He also said, like many others who live in Britain, “I predicted it.”)

Maybe in a city where everything is showy real estate, the collective shrug over Trump’s election shouldn’t surprise. Xu Zhen, one of the most highly collected local artists, intends to run with it: his studio just opened Xu Zhen Store on the West Bund, a consumerist candy shop of tracksuits, sunglasses, and furniture, branded by the artist. There is none of the hand-wringing here that the art world has become too commercial — it is proudly so. Billionaires do not just hold interest in the culture, they determine it.

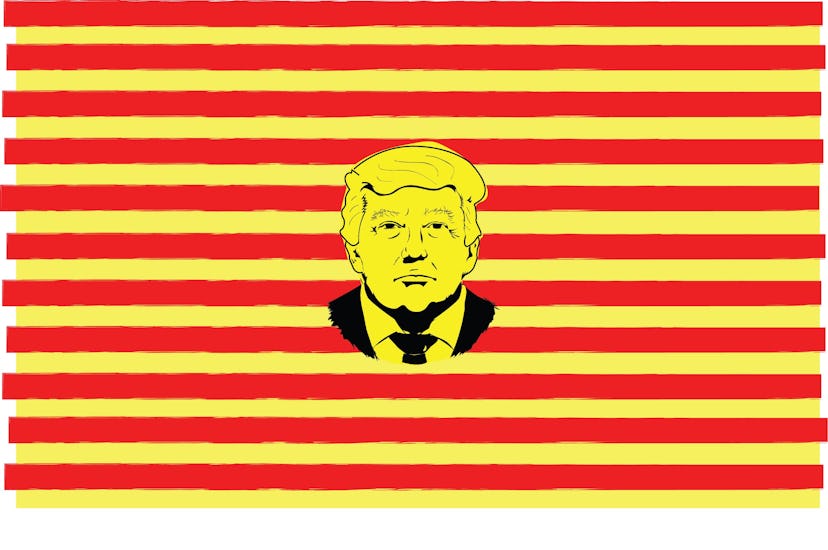

In general, the Chinese cultural elite’s reaction to the election of a man who once claimed “China is raping us” to the American presidency was amusement, ambivalence or dismissal. As a recent Global Times editorial noted: “to impose a 45 percent tariff on imports from China is merely campaign rhetoric.” To China, he’s shanzhai — in other words, Donald Trump is counterfeit goods.