Yoko Ono: Cutting Edge

Long overshadowed by her famous other half, Yoko Ono finally gets her due as a pioneering artist.

In 1971, Yoko Ono created a one-woman exhibition for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She printed a catalog and placed ads in The New York Times and The Village Voice that showed her outside the museum carrying a large letter F, lined up in such a way that the sign out front seemed to read museum of modern fart. She also made a film: Visitors exiting MoMA were asked by a cameraman whether they’d seen Ono’s show. A few said they had, others said they hadn’t but planned to. As it happened, no one could have seen Ono’s MoMA show. Taped to the ticketing window was her ad, bearing the hand-written wordsthis is not here.

The Museum of Modern [F]art was yet another in a long line of pioneering conceptual artworks that Ono had been making since 1960, when she began hosting a Who’s Who of New York’s avant-garde in her cold-water loft in TriBeCa, then a seedy part of town. John Cage and La Monte Young were regulars; Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Beuys, Max Ernst, and Peggy Guggenheim also took part in the gatherings.

Now, 44 years after Ono imagined that 1971 guerrilla-style happening at MoMA, she is finally being officially recognized by the museum. Opening May 17, “Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971” focuses on that vital first decade, when she forged new mediums and honed her singular voice. The exhibition comprises text-based works, objects, performances, recordings, and experimental films that leave no doubt of her seminal influence on conceptual art.

The ad for Museum of Modern [F]art, 1971. Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art Library, New York.

“She gave a new status to the artist,” says Christophe Cherix, MoMA’s chief curator of drawings and prints, who, along with Klaus Biesenbach, the museum’s chief curator at large, organized the show. “She thought about the artist not just as someone who provides something for you to look at—because she’s not always the maker of things, or even the performer. She’s an instigator of ideas.”

In fact, she was thinking about “conceptual” art well before anyone was calling it that. Having arrived in New York in the mid-’50s, Ono, who was born in Tokyo, carved out her place in the experimental art world soon after leaving her studies at Sarah Lawrence College. She was one of the few women among the artists, poets, and musicians in the nascent Fluxus movement, whose members championed an anarchic multimedia approach and a DIY aesthetic. Before founding Fluxus, George Maciunas gave Ono her first solo gallery show, in 1961. Visitors were invited to drip water onto cloths dyed with Japanese ink, and to step on a painting—a reference to a period starting in the 17th century, when suspected Catholics in Japan were forced to walk over images of Christ; those who refused were killed. “I was very impressed by the courage of the Catholics,” Ono told me recently. “I first heard that story in middle school, and I thought I wanted to be a person who had the same kind of courage.”

Her early works were radical in the way that they delivered concepts, not things; her groundbreaking book Grapefruit, which she self-published in 1964, consists largely of recipes for art and musical works, or sets of instructions and ideas that anyone could realize. (“Let people copy or photograph your paintings. Destroy the originals,” she wrote presciently.) In this way, she ceded control as an artist; rather than present a finished piece, she invited collaboration to complete it. “Very early on, she tried to talk directly to the viewer and tried to change his perception of the world,” notes Cherix. “And that is already political.” In her Cut Piece, first performed in 1964 in Kyoto, Japan, and then at New York’s Carnegie Recital Hall in 1965, Ono sat in silent surrender onstage as audience members took turns snipping off her clothing with a pair of scissors. Just as feminism was hitting the mainstream, Ono was already using the female body as a medium for art and protest.

Ono performing Cut Piece, 1964, at Carnegie Recital Hall, in 1965. Photograph by Minoru Niizuma/Courtesy Lenono Photo Archive, New York.

“I’m very controlling, as all artists are,” she told me one chilly afternoon in February, the day after her 82nd birthday. The night before, she had celebrated with a jam session in a downtown recording studio with her son, Sean Lennon, 39, and close friends—something she’s done every year since she turned 70. We were sitting on white director’s chairs in her large open kitchen in the storied Dakota building on Central Park West, where congratulatory flower arrangements covered nearly every available surface. Dressed in a fitted black sweater, black pants, and sky blue socks, Ono cut a tiny yet commanding figure against the apartment’s soaring ceilings. “One day I thought, I don’t want to let people touch my work. And that’s when I realized, Wait a second! That’s why I have to do it.”

In 1966, John Lennon dropped by Indica Gallery in London to check out her show. Climbing a ladder to view one of her works on the ceiling, he looked through a magnifying glass placed at the top and was pleased to discover that the tiny letters above him spelled outyes. Soon, the “lone wolf,” as Ono calls her younger self, joined forces with him, and Ono quickly became, in the words of Lennon, “the world’s most famous unknown artist. Everyone knows her name, but no one knows what she actually does.”

Her arrival at MoMA should clear up that mystery. The wide-ranging show will include her once scandalous Film No. 4 (Bottoms), from 1966 to 1967, which fills the screen with the assorted bare buttocks of people walking, and Half-a-Room, her 1967 installation of bisected domestic objects, a rumination on incompleteness sparked by Ono’s waking up one morning to find that her husband at the time, the film producer Tony Cox, hadn’t come home. Also featured, of course, are her collaborations with Lennon, who had attended art school himself. One of their first conversations, she recalled, was about René Magritte and Wassily Kandinsky. “John was very well established in his field, but he realized that I was very established in mine, too. So it was a meeting of two souls in a very powerful way.”

Leveraging their fame for antiwar activism, Ono and Lennon invited the press into their hotel suite during their honeymoon and spent the week in bed discussing world peace. It’s unlikely that any piece of performance art since has received the kind of worldwide attention lavished on Bed-In, first performed at the Amsterdam Hilton in 1969 and later that year at a hotel in Montreal, where they recorded “Give Peace a Chance,” the first single for their newly formed Plastic Ono Band. “The world didn’t understand it,” Ono recalled of Bed-In. “And there’s that hatred that came to me because of what? Jealousy, maybe. That I was with John. Art is the most important thing for me, and if I had been concerned about what people said, I wouldn’t have made those pieces. But they didn’t stop with attacking me; they were attacking John as well. I was concerned that just because of love, he was destroying his career. Well, he certainly didn’t destroy it. But nearly.”

Born into a wealthy Japanese banking family on her mother’s side and aristocracy on her father’s, Ono was fiercely independent, even as a child. Both parents were deeply cultivated. She remembered her father, a banker, translating one of the first books about Constructivism into Japanese; her mother was an accomplished painter. At age 3, Ono was sent to a music school for the gifted where she studied piano, composition, German lieder, and opera. Later, she became one of the first women accepted into the philosophy program at Tokyo’s elite Gakushuin University. Because of her father’s job, the family moved back and forth between Japan and America. They lived for a time in San Francisco and then moved to Scarsdale, New York, before Ono enrolled at Sarah Lawrence in the early ’50s. Even as she made her way into the New York underground, she insists she “never suffered from self-doubt.”

That fearlessness has served her well. In 1971, one month before she was given her first solo museum exhibition, at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York, Ono and Lennon appeared on The Dick Cavett Show. At the time, Cavett was considered television’s reigning highbrow host, yet to watch him introduce Ono as “one of the most controversial ladies since the Duchess of Windsor, Wally Simpson, kept the duke from becoming the king” and smirk his way through Lennon’s impassioned commentary on Ono’s art, is to wonder at that reputation. Still, while her celebrity overshadowed her career as an artist, it gave her a platform such as Cavett’s show to announce her museum survey, which drew unruly crowds to its opening when a rumor circulated that the Beatles would be playing a reunion concert. Many of the pieces included in that Everson exhibition will also be at MoMA. Ceiling Painting is the work that Lennon climbed in 1966, and White Chess Set, made that same year, is composed of a white chessboard with all-white pieces, making it impossible to end up with a winner, leaving peaceful resolution as the only option.

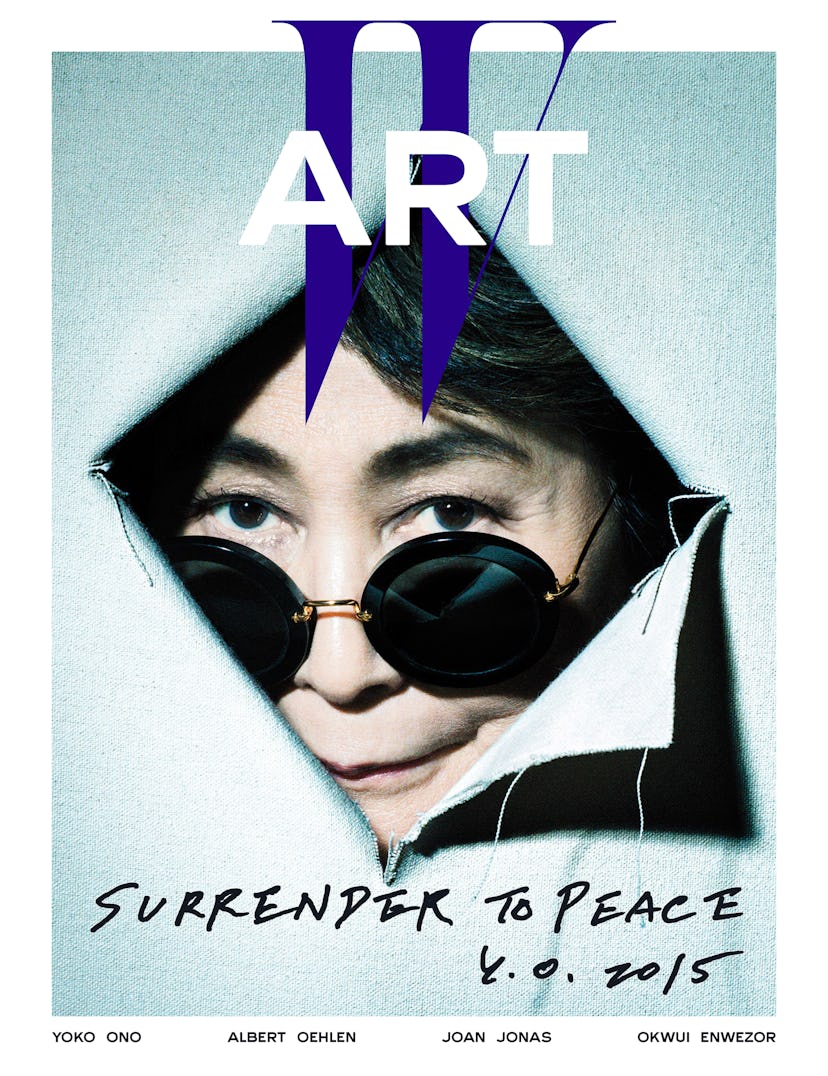

In advance of her MoMA opening, W commissioned Ono to revisit two works. For the cover of this magazine, she riffs on a photograph taken by Maciunas of a hand-painted poster she’d made for her 1961 concert at Carnegie Recital Hall, which shows her peeking through a tear in a canvas. For the images in this story, she chose her seminal Cut Piece, which she last performed in 2003. Now, however, she wanted to play the role of the person doing the cutting. “I’ll be the aggressor, not the victim,” she said. She opted for a model dressed in denim, “since we are all unisex.” Her original idea came from a story about the Buddha and his willingness to give up everything, including his family, until he achieved understanding of the human condition. “I wanted to show the suffering that women go through,” Ono said. “Something is taken from her.” Cutting clothing with scissors, she explained, imposed square lines on a woman’s naturally curvy shape.

Ono took command of the shoot, her movements bold and precise. She made cuts in vulnerable places—across the neck, knee, and bra strap—tossing each square of fabric in a pile on the floor. The gleaming long shears she’d requested looked sinister in her small hands. “I didn’t know it was such a dangerous piece,” she told me afterward. “The scissors were so sharp—it scared me to cut somebody.” I asked if she felt powerful this time around. “No,” she said quietly. “It was more like I was inside a powerful game. I was exposing a sculpture.”

Ono will not be present in any formal way for her conceptual performance pieces, as the artist Marina Abramovic was for her own survey at MoMA, though she may occasionally show up unannounced to participate in some of her works along with visitors. (She will be seen enacting Cut Piece in the 1965 filmed version by Albert and David Maysles.) But, of course, she remains highly visible thanks to her peace activism via public art projects, recordings, and social media. At the Dakota, I asked how she felt her work resonated with the current climate of protest and ever-present global demonstrations. “I think it’s very interesting that when John and I stayed in bed in order to do those peace activities, not many people were there with us,” she replied, alluding to the ridicule they endured. “Now I think the whole word is activist.”

Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece

Yoko Ono in an original work she created for the cover of W Art, May 2015. Photographed by Pari Dukovic.

Yoko Ono reimagining her 1964 performance of Cut Piece for W.

On model: Current/Elliott shirt, $198, currentelliott.com; Araks bra, $84, araks.com; A.P.C. jeans, $200, apc.fr; Falke socks, $28, the Sock Hop, New York, 212.625.3105; Strange Matter sneakers, $360, barneys.com.

Yoko Ono reimagining her 1964 performance of Cut Piece for W.

Yoko Ono reimagining her 1964 performance of Cut Piece for W.

Yoko Ono reimagining her 1964 performance of Cut Piece for W.

The ad for Museum of Modern [F]art, 1971. Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art Library, New York.

Bag Piece, 1964, performed in 1965. Courtesy of George Maciunas/The Museum of Modern Art, New York/The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift.

At her first solo gallery show, in 1961 in New York, with Painting to See in the Dark (Version 1), 1961. Courtesy of George Maciunas/The Museum of Modern Art, New York/The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift.

George Maciunas’s photograph of the artist with Works by Yoko Ono, 1961, her poster for a concert at Carnegie Recital Hall in New York. Courtesy of George Maciunas/The Museum of Modern Art, New York/The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift.

Stills from Film No. 4 (Bottoms), 1966–67. Courtesy of the artist.

Ono with her work Half-a-Room, 1967, at Lisson Gallery, London. Photograph by Clay Perry/courtesy of the artist.

Grapefruit, 1964. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York/The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift.

Ono performing Cut Piece, 1964, at Carnegie Recital Hall, in 1965. Photograph by Minoru Niizuma/Courtesy Lenono Photo Archive, New York.

Ono and John Lennon’s War Is Over! If You Want It, 1969. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York/The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift.

Model: Vlada Roslyakova at Women Management. Set design by Viki Rutsch. Ono’s makeup by Christine Cherbonnier for Chanel at The Wall Group; model’s hair by Tamara McNaughton for Wella Professionals at Management + Artists. Model’s Makeup by Georgi Sandev for Chanel at Streeters. Nail Technician: Honey at Exposure NY. Photography assistants: Amy Moore, Fernando Souto, Matthew Kanbergs; fashion assistant: Hanna Corrie; set design assistants: Boaz Tcherikover, Anastasia Dudin.