Karl Lagerfeld’s Spring ’92 Chanel Couture Show Was “Diabolically Body-Conscious”

Welcome to Forgotten Runway, a deep dive into some of the more niche presentations in fashion history—which still have an impact to this day. In this series, writer Kristen Bateman interviews the designers and people who made these productions happen, revealing what made each one so special.

The name behind the theme for 2023’s Met Gala and Costume Institute exhibition is quite a ubiquitous one. On May 1st, “Karl Lagerfeld: A Line of Beauty,” will celebrate the life, work, and lasting effect the designer had upon fashion. And while some of his moves might be considered controversial today, there’s no denying Lagerfeld singlehandedly changed the industry as we know it during his tenures at Chanel, Chloé, Fendi, and even Balmain. He injected ingenuity and modernity, but more importantly, humor and wit into household labels like never before. There are plenty of examples—but one runway show that made an everlasting impact beyond the runway, catapulting itself into the pop culture canon and onto Pinterest boards forever? Chanel’s spring 1992 haute couture presentation.

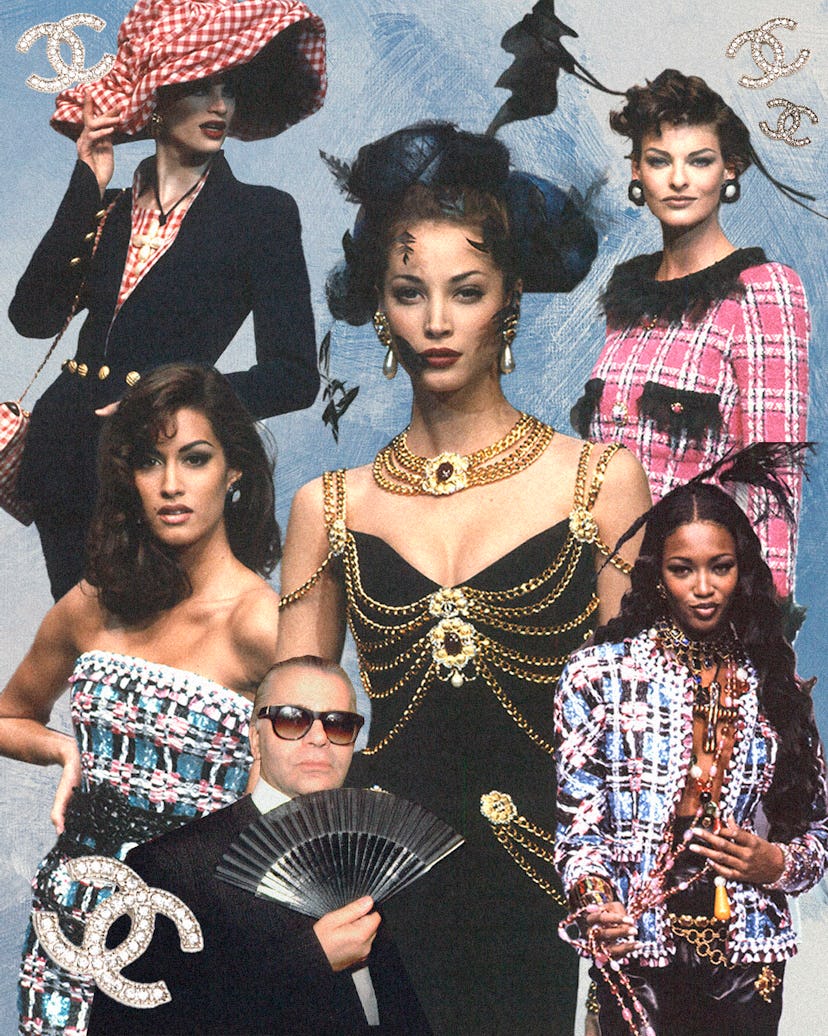

Perhaps you’ve seen the famed little black dress Christy Turlington wore on the runway, layered in decadent, chunky, gold-and-glass chain jewelry across the shoulders and torso. Without Lagerfeld’s touch, it would have been an unassuming, perfectly tailored slip. But the addition of the jewelry was pure camp, and launched the look into the annals of fashion legend. The same dress was later worn by Penélope Cruz in Pedro Almodóvar's Broken Embraces, and later, by Lily-Rose Depp on the 2019 Met Gala red carpet.

But that was just one standout piece in a collection filled to the brim with classic Lagerfeld Chanel-isms we know today. Think: structured white gowns and little jackets puffed with black taffeta, black-and-white cocktail dresses covered in costume jewelry, exacting tailored blazers and wide-brim hats, gold jeweled buttons on suit jackets, little gloves, low-slung chain belts, and logos galore. Spring 1992 was very much a haute couture show, but the dynamic accessories, styling, and casting allowed for mass appeal beyond the very narrow world of Paris couture. This was a collection that cemented Lagerfeld’s eye for breaking tradition.

Lagerfeld’s ’90s era at Chanel might just be one of his most celebrated periods of all time. There were supermodels! Logos! Jewelry-bedecked dresses! The classic Chanel bride! Lagerfeld took Chanel on a wild ride with Naomi Campbell, Christy Turlington, Linda Evangelista, Claudia Schiffer, and Helena Christensen by his side. The designer joined the French house in 1983, but his revival and distinct vision of the label—once an old, dragging luxury house—came to fruition in the early ’90s. That little black dress become so popular, so lasting, that Johnny Valencia, owner of Pechuga Vintage, was recently asked to track it down for a client. “Karl knew his buyer,” Valencia explains. “By decorating a classic shift dress with costume jewelry, the German designer pushed one of Chanel’s most profitable departments: costume jewelry.” The lasting power of the dress may be credited to the aforementioned Lily-Rose Depp moment, however—a Chanel muse for the next generation. “That brought the ensemble to a new demographic, when she stepped onto the Met Gala’s carpet in 2019, exuding once more the ’90s supermodel allure,” he says. “And then came the dupes. In 1926, Vogue stated that Chanel’s LBD was the de facto uniform ‘for all women of taste’. I wonder what Chanel would’ve thought of the sheer amount of girls wearing a piece so far removed from the woman she emancipated, but one that brought together the army of Cocos she set out to forge?”

But perhaps the most daring moment from the spring 1992 haute couture collection was the ecstatic vision of trompe-l’œil through opulent outfits that defied convention and played with logic. Those tweed jackets covered in glowing, watercolor-like prints? They were actually made of raffia. “Can we talk about the fact that the jackets were tailored so tightly they had to be zipped up from the back?” Valencia says. “Suzy Menkes once said that Karl Lagerfeld had to destroy Chanel, otherwise he’d just become a caricature of [Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel], and for spring 1992 haute couture, Lagerfeld did just that—this time, quite literally, with the silhouettes he sent out, which he deemed ‘diabolically body-conscious’ and with the tattered skirts in chiffon he presented. The latter were inspired by Karl's favorite book, Pleasure of Ruins. If Chanel had freed the women she dressed, Karl bound them once more.” But this time, he’d put them in a majestic, magpie cocoon of jewels and accessories.

Looking back at Chanel’s ’90s era, the 1992 collections feel particularly representative of Lagerfeld’s bold new vision. There’s a reason why collectors obsess over this specific period, after all. One could argue the spring 1992 couture collection was one of the most prolific moments of Lagerfeld’s career, when the designer asserted his voice and vision as Chanel’s future legacy. “Lagerfeld was intimately familiar with the Chanel style, and he really knew how to deconstruct it so it would be ‘signature Chanel’ but look innovative and modern,” the fashion historian Einav-Rabinovitch Fox says. “He combined the classic Chanel style with street styles and denim that appealed to younger audiences and made it relevant to them, which is another reason why his designs are so popular, because they are timeless and contemporary at the same time.”

Left: Claudia Schiffer at a fitting for the spring 1992 Chanel haute couture show. Right: Schiffer, Karl Lagerfeld, and Nadja Auermann backstage at the show.

Claudia Schiffer closed the haute couture show in 1992 as the bride, wearing an epic veil and front-zip gown with a bustier structure and blossoming skirt. In 2023, it’s ironic that a couture show—one of the most niche segments of fashion—could have such a lasting influence on an industry at large. Add that to the fact that Lagerfeld historically hated looking back. “Karl wasn’t nostalgic,” Valencia adds. “He hated reminiscing about the past. His work was imbued with his own obsessions of the now.”