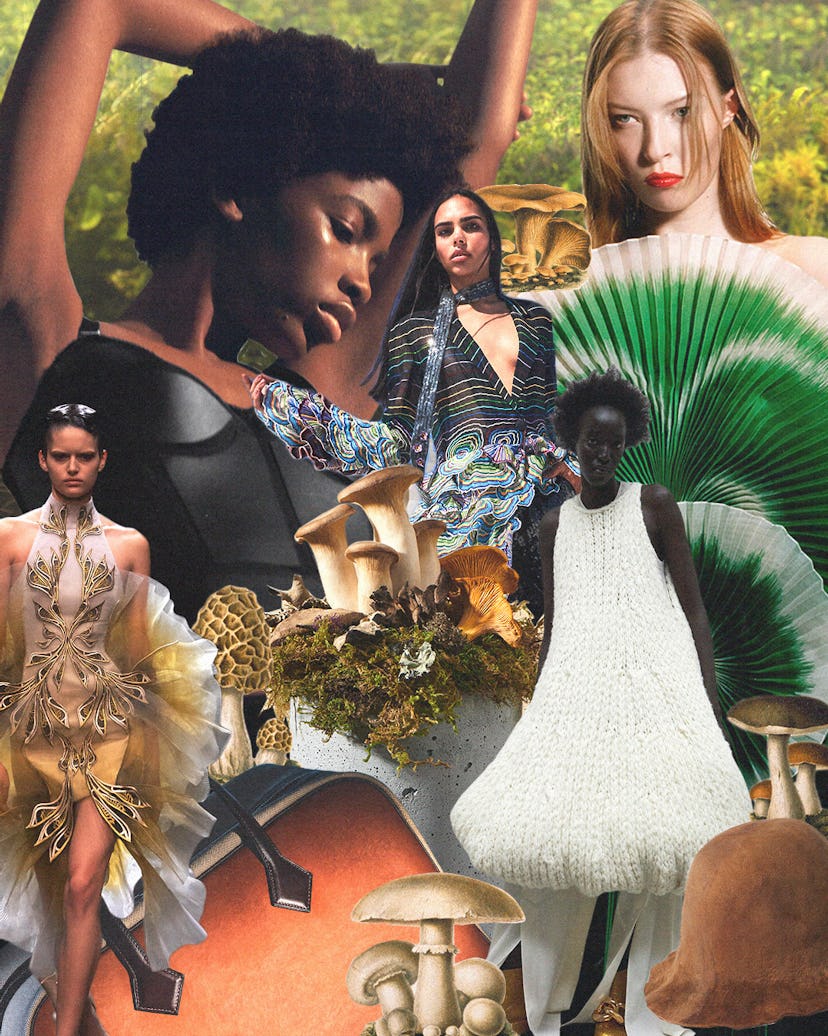

By now, you’ve probably been overexposed to headlines with declarations about how “the future of fashion is fungi.” While mushrooms have been an important part of the natural world for millennia, this newfound adoration in popular culture is merely a resurgence of collective appreciation that originally sprouted back in the late ‘60s. For spring 2021, we’ve seen the likes of Iris Van Herpen, Rahul Mishra, Jonathan Anderson, and Daniel Del Core pulling inspiration directly from the enchanting folds of fungi and using this intense moment of universal transcendence to fuel their creativity. But the biggest difference now is that progressive designers aren’t simply using mushroom iconography as a graphic motif to press on to their merchandise—many of them are considering how to integrate fungi into the fabrics of their raw materials.

The recent push toward sustainability has caused a major shift in the fashion industry, a reckoning that has been long overdue considering the increased demand for more eco-friendly ethics and standards. As Intersectional Environmentalist founder Leah Thomas explained in a Twitter thread, there are so many nuances within the sustainable fashion space because it’s still in transition. But the demand for sustainability, human health, and animal welfare is growing exponentially. Given that mushrooms operate as a natural recycling system, mycelium (the fuzzy, fibrous feeding network that helps fungi grow) serves as a multi-functional option for more mindful packaging as seen with companies like Ecovative Design and their suite of biodegradable alternatives. The next step involves introducing mycelium “leather” goods to the commercial market, as demonstrated this year by Stella McCartney and Hermès.

For hundreds of years, many industries have relied on petroleum, or traditional animal source products. Switching to consumer goods made out of vegan “leather”—a textile that is usually manufactured from polyurethane or polyvinyl acetate—was a quick fix with a low cost, but studies have shown that these synthetic substitutions can still be harmful to the environment. No matter how you dress it up, plastic is still plastic, which means biodegradable products of this kind will outlive us in a landfill.

Mycelium leather is considered a better option because of the low-energy manufacturing and biodegradability aspects. (The roots can be grown on sawdust and other byproducts as opposed to acres of land which has less of an environmental impact.) On the other hand, it’s still so new that nobody really knows what the long-term durability of mycelium products looks like yet.

Companies like Bolt Threads, which has been at the forefront of biotechnological innovation since 2009, have also entered the mushroom fashion fold. When Dan Widmaier, CEO of Bolt Threads, noticed the fashion industry was underserved as far as consumer products were concerned, he made sure the company’s mission involved bringing in new materials to fix problems in our consumer marketplace by looking to nature first. He likes to credit Mother Nature for “giving us a four-billion-year working example of a perfectly circular materials economy.”

The company debuted their foray into luxury fashion in 2017 when presented with the opportunity to partner with McCartney to create a dress made out of Microsilk (silk proteins spun by spiders), which was later displayed at the Museum of Modern Art. From there, Bolt Threads expanded into the production of mycelium as a material with leather alternative Mylo, followed by a consortium including Stella McCartney, Adidas, Lululemon, and Kering.

When Isaac Larose and Florence Provencher Proulx established EDEN Power Corp in 2019, the vision was to introduce an eco-conscious streetwear brand to the market. According to Larose, their intent with the project is to better educate themselves and others by using the product as an application of the idea. He elaborates on how their mission is to show alternatives that shift the attention toward the people who have been doing the groundwork in social justice and environmental justice, adding “we're not creating really anything, the stuff is already there.” Every season, EDEN builds a uniform for a department of a fictional company that tackles a specific environmental issue. Larose happens to be a fan of foraging, a hobby that he has enjoyed doing for years, so it made sense that they would dig deeper into fungi territory.

While they don’t have access to mycelium leathers at this time, Larose hasn’t let that stop EDEN from exploring all the possibilities through collaboration with smaller artisans. “[Mycelium leather is] quite exclusive to a couple of bigger brands right now, which I think is a really good thing by the way,” he says. “It's really important that they have the support from those bigger brands to do the research and the development. That’s a normal process.”

EDEN’s “Mycelium” collection for Spring 2021 features an iconic Amadou mushroom hat that was inspired by the mycologist Paul Stamets. The spongy piece took months for a Transylvanian artisan to make by hand, and a slight variation is currently in the works—along with homeware products that will be made using the same material. EDEN also sells a wine cooler, planter, and brick made out of mycelium that was grown on hemp agricultural waste; the lookbook for the collection was shot on location at Les 400 Pieds de Champignon, a farm in Montréal that grows mushrooms for restaurants in the region. Lately, Larose has also been busy experimenting with mushroom ink, which he’s enthusiastic about weaving into the brand.

Of course, regenerative innovation on any level is an expensive endeavor. Accessibility is a huge factor in conversations about sustainability and there is a lot of money to be made in the development of technology around it. “It can be done, but it's so expensive,” Larose says. “That's the main problem right now for us, our stuff is really, really expensive and we understand consumers that don't want to pay that kind of price... Our goal is to change the spotlight and see what's possible. What we're hoping for is that bigger brands are going to copy, not the style, but the idea.”

As someone who covers the world of agriculture in-depth from all angles, Whitney Bauck—a Brooklyn-based journalist on the pulse of fashion, climate, and religion—has seen the counterproductivity of patented materials when only one company owns them and how doing so evidently creates more problems. Her main concern is getting mycelium-based materials in the hands of smaller designers, and she’s most curious about how the companies invested in biotech development will help “the little guys” make this transition since it will ultimately have a greater impact on their businesses. She adds, “That's one of the questions to me, how much is this going to be something that other companies can innovate on and figure out their own way of doing versus how much of this is going to really benefit the one or two companies that come out on top and have proprietary materials they’re marketing as more sustainable?”

Widmaier claims there are discussions at Bolt Threads around planning programming to support smaller designers that are passionate about working with materials like Mylo. The idea would be to distribute a set amount of square feet for each designer to use, but Bolt Threads is nowhere near that scale yet. He argues that this new class of materials will become more accessible over time as it becomes more mainstream, but it’s taken so long because deep technical innovation was not the driving force in fashion for a long time despite being “an industry that's baked into embracing change.”

But Widmaier has come a long way from where he started as “one dude, a box full of spiders, and an empty bed.” He remembers how, just over a decade ago, nobody working in fashion wanted to talk about sustainability. Now that it’s all happening in real-time, Widmaier is eager to see how consumers will adapt after coming out of the pandemic—since history shows there can often be a collective shift in behavior after periods of scarcity.

“At the end of the day, the consumers are the ones driving the bus,” he concludes. “If you can identify where they're going, we're all going there.”