Back to the Bauhaus

Mention the word "Bauhaus" and what comes to mind for most is a boxy white building, a tubular steel chair or a typeface. But the hugely influential German art and design school was much more...

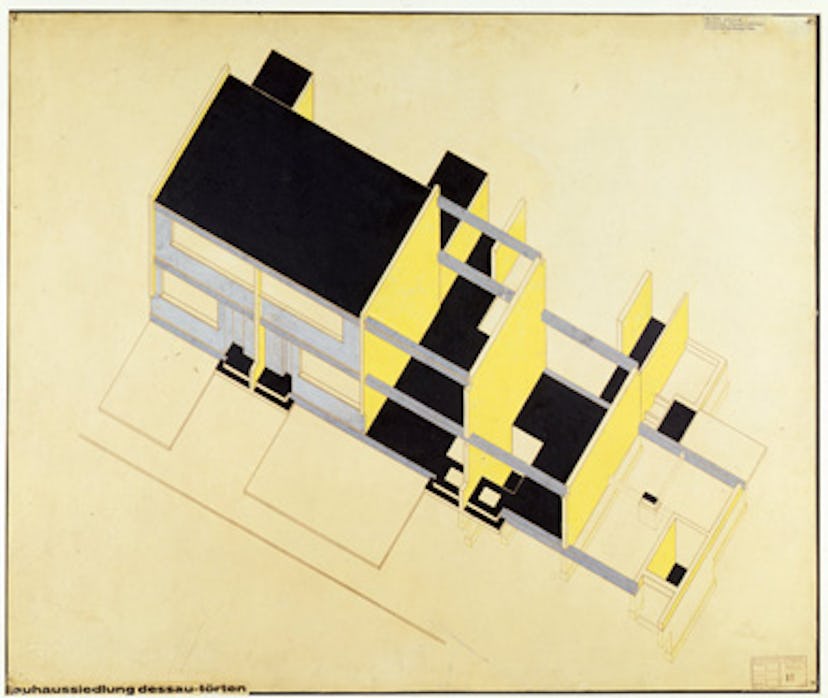

Mention the word “Bauhaus” and what comes to mind for most is a boxy white building, a tubular steel chair or a typeface. But the hugely influential German art and design school was much more wide-ranging and experimental than is generally believed. That’s the premise of MoMA’s new exhibition, “Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshops for Modernity,” which opens next week. Founded in 1919 in the aftermath of WWI, the Bauhaus was equal parts lab, salon and cultural think tank, bringing together such talents as Mies van der Rohe, Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Anni and Josef Albers. Co-curated by Barry Bergdoll and Leah Dickerman, the MoMA show—its first on the Bauhaus since 1938—reflects the school’s output and ongoing impact in the areas of furniture, architecture, graphic design, photography, painting and textiles, among others. As a temple of modernism, MoMA owes a great debt to the Bauhaus, which, as Dickerman points out, “is in the very DNA of MoMA.” We recently paid a visit to Dickerman to discuss the exhibition’s relevance and revelations.

Yes, it’s basically true. For the 1938 exhibition, Gropius only covered the years that he was director. But he gave short shrift to his first years, so it focused on the years between 1923 and 1928. He was sort of laying claim to the word Bauhaus and what a Bauhaus legacy in America might be.

What’s different about your show? We’re bringing together a huge range of objects, 450 of them, including work by the faculty, work by the students, fine art made for traditional exhibitions, mass-produced objects … Our show really focuses on Bauhaus as a historical institution and the years from 1919 to 1933. “Bauhaus” is often used as shorthand for international modernism that’s unmoored from any specific historical context—you hear “Bauhaus” and often somebody is talking about something that’s not at all directly linked to the Bauhaus. We’re really focusing on the idea that Bauhaus is not a style, it’ s a school; there isn’t one Bauhaus style, there’s many Bauhaus styles.

Has it been misinterpreted as a style then? Definitely. If you read magazines you see things that say “Bauhaus Architecture” and there’s an expectation about what that is—that it’s going to be white cubic lines, clean finishes, tubular steel furniture. But it’s much more diverse than that and it’s not only architecture.

Why do think it was such an enduring influence? Certainly the tides of history are at play here. The fact that the Bauhaus was shut down by the Nazis and its teachers and students went all over the globe—to Latin America, South Africa and the States. In the US of course many of the Bauhaus emigres became important teachers in various art schools—at Black Mountain College, at the Illinois Institute for Technology. Gropius taught at Harvard and Albers taught at Yale, and they became incredibly influential teachers. For several generations of artists, the probability that you would have studied with a Bauhaus teacher was huge.

What makes this show timely? The Bauhaus put painting, design and architecture on equal footing. The faculty that Gropius assembled included many prominent avant-garde artists, architects and designers so there was this conversation over fourteen years between artists working in different mediums about what the nature of modern art should be in this new age of technology, industrial production and economic crisis.

What did you learn doing this show? Any major surprises? There’s a coffin design—a six-foot gouache—made by Lothar Schreyer who was the first master of the theater workshop. It wasn’t put into production,although he made two coffins in which his parents were buried and the lids of those coffins were displayed in Schryer’s studio at the Bauhaus. Kandinsky wrote about how weird that was.

Were there any discoveries about the Bauhaus artists themselves that intrigued you? There’s funny things: Johannes Itten was a shaman-like figure. He wore a shaved head and had priest-like robes and introduced an almost yoga-based, physical practice to the study of art. So he had his students doing isometric exercises, breathing exercises and body movements. He also insisted on a garlic-based diet. In fact, in diary entries from the time, you read that people are commenting on the smell of Bauhaus students. Because they were eating so much garlic.

Bauhaus 1919-1933 opens at MoMA on November 8. Portrait by Christos Katsiaouni; all art courtesy of MoMA.