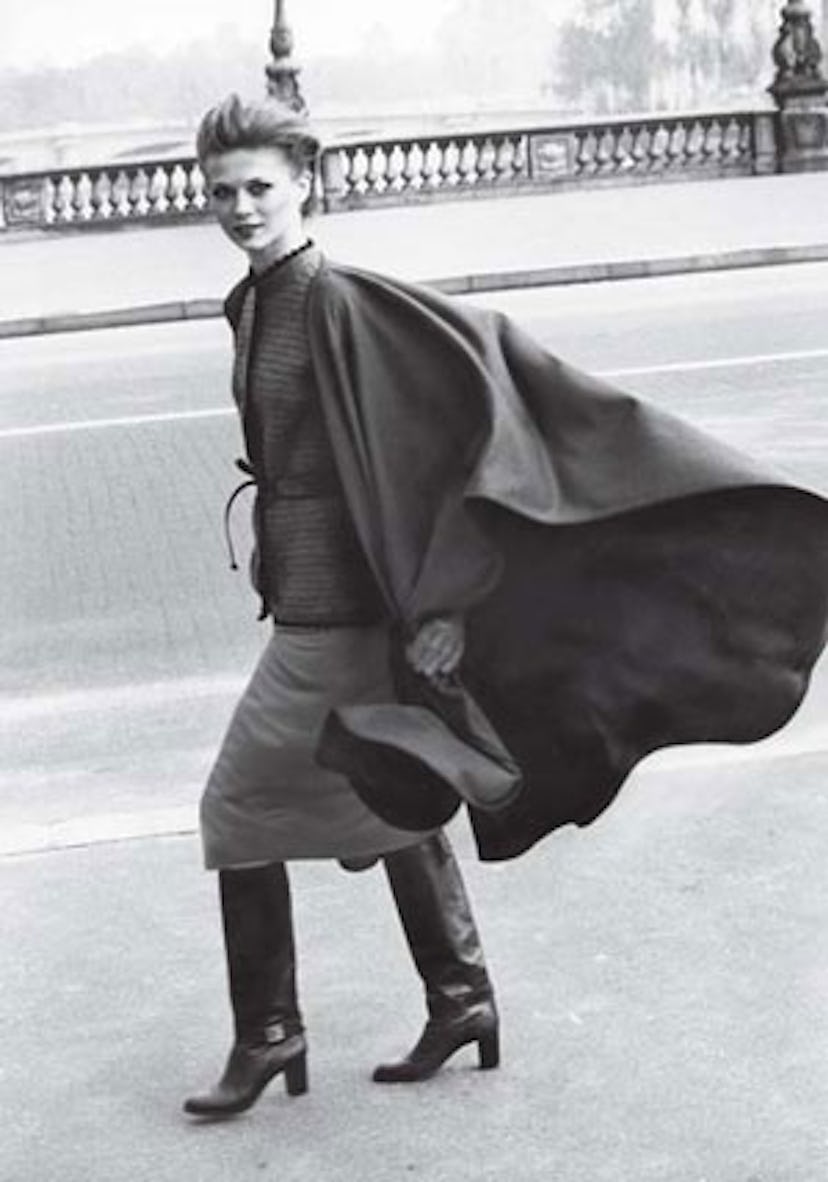

On my first trip to Florence, I saw her. It was a brisk autumn day, my junior semester abroad. She was crossing the street ahead of me, her olive cashmere cape flowing behind her. She had a handsome but not beautiful face; it was a face that had seen a few of life’s turns—the lovers and the heartaches, the pull of time—and understood them. I couldn’t take my eyes off her. She was stunning, composed yet mysterious, as she clipped along in her smart boots, hair slightly tousled, very little makeup, gold earrings hanging like bobs. Others on the sidewalk turned to look at her because they couldn’t help themselves, and all of us wondered if she was famous. She didn’t notice me, of course; she wouldn’t. As quickly as she appeared she vanished, even as I longed to run after her, saying, “Tell me everything you know.”

When I returned to Paris, I bought myself a cape. In fact, I bought two. The first was a mistake; it scratched. The second was perfect, lined with silk. I spent money I didn’t have. Those capes are gone now: I gave the halfhearted one away, and wore the good one until it tattered. What remains is an appreciation from which I’ve never fully recovered. I hope I never do.

What my Florentine beacon had, of course, was style—that certain something, that seamless interface between the self and the outside world. When it’s all of a piece, you notice. But what is style if it’s not only skin-deep? The dictionary defines style as “a manner of doing something,” and that something, let’s agree, is living.

Style begins with the people passing through one’s life, the harbingers we push against and the stylemakers we want to clone. Some are famous, some not. Style grows from admiration, from longing, from discrimination—and, yes, from love. It’s all the places you’ve been to and the people and the moments you’ve known: the parts you’ve adopted, to keep forever, and transformed. We wear our history in our hearts and on our backs.

My first time abroad some 30 years ago turned out not to be about what I learned in books. The study was about living. How to eat, to dress, to discern, to move in unknown places, to see, to know. I studied the paintings in the Louvre, but I also studied the people looking at the paintings. In France I had a teacher who wore only five impeccable outfits, one for each day of the workweek. I learned very little French from Joelle Blot, but I can tell you, all these years later, that Tuesday was the wool camel skirt, the form-hugging ivory sweater, the silk scarf with the birds, the cordovan pumps, the garnet ring. It was a certain level of organization I’d never seen before. Her five good pairs of shoes had been resoled with rubber to make them last and last. She wasn’t a style maven, but she taught my hungry eye something of European bourgeois classics. And just as with writing, you must study the classics before you can knowingly add your own funk.

The work of style starts early, with all kinds of mistakes, and only rarely does one encounter native speakers. I knew a girl in college whose mother had been a model for Dior. The girl wore her mother’s old couture and mixed it with jeans and fishnet stockings and short kilts and leather jackets. She rode her bicycle to class in these gorgeous costumes, her hair a long golden rope down her back. She drove the boys wild—including, as I recall, my boyfriend at the time, who always lit up when he saw her. It was all right: Everyone did. No one else on campus could have worn those clothes and not looked like they were putting it on, but she wasn’t dressing for our approval—she was creating a self.

Real style is a bit of the snob, let’s face it. It’s choosing this but not that. It is deciding for one’s own purposes what is fine. What represents not just the head but also the soul. I’ve known scores of folks who dress beautifully but who lack style. The clothes are put on top; they don’t come from the root. There’s a difference. I once went out with a guy who dressed like an unmade bed. He didn’t have money, but he had terrific style. He’d camp in the woods for days, building huts, warbling with birds, and walk out looking like a movie star. When his belt broke, he took some brightly colored yarn, braided it, and somehow looked the height of chic. Once we went to a very fussy restaurant in Boston. For the occasion he combed his hair. The maître d’ treated him as if he was a visiting dignitary. And he was, that king of the woods.

For the rest of us, it’s trial and error. My two-year-old niece tries on a hat and studies her reflection. She tips her head, adjusting her face, already someone, already with a sense of who she wants to be. Strong characters—even toddlers—always do. I have three daughters, all with shared blood, history, and humor, yet each has a distinct style. The eldest takes her inspiration from hip hop and circus folk; our middle girl is the classicist, more in line with Blake Lively; and the youngest is a colorist, a poet; as early as five, having never been to Paris, she announced, “Paris is the place of my soul’s imaginings.”

Of course, a young person’s style is all about “Look at me.” It’s a declaration. I watch my daughters try it on, the business of becoming. They stand before the mirror, and the first face they show the glass is the real feeling the garment gives them; the second face is the person they want to be while wearing it. The pose they strike for the mirror is an imprint from someone who has shaped them.

For a long time my own style was hit-or-miss. I tried to convince myself of things. I went for what worked on someone I admired but that wasn’t right for me. Then, in my 30s, I found my groove. It was no longer about trying but about being. Style says, “This is who I am—this is my signature, my voice, my scent, my colors, the cut I like best. This is me, good as I am.” It’s in the eye, the smile, the gaze, the laugh. It’s who I saw crossing the street in front of me in Florence.

If the creation of one’s style begins with aspiration, the maintenance relies on keeping in touch with old friends. You go to that same blouse or scent, that lipstick or heel, because in the past it served you and brought you to happy times, or rode you through the storm.

Style is all about character. In the end, they are the same. What I know, what I try to tell my daughters, are some of the things I’ve picked up along the road. The eyebrow is key—just ask Picasso. Take care of your heels, and they will take care of you. Don’t buy it if it only fits the you who is five pounds lighter. In time your face will mirror your character, no matter how many tucks or nips—all the more reason to laugh well and often, and leave the snark for someone else’s sour puss. After 40, a well-fitted bra can retrofit the whole architecture. Generosity in all things—from work to living. Have one dress that showcases your strength and another your smarts, and a third that inspires you to flirt. Your mind is your sexy booty. A mule is a pack animal, not a shoe you wear. Boots are made for confidence. If you must be matchy-matchy, for God’s sake show some wit. Less is more, with the following exceptions: good manners, thread count, self-deprecation, and real knowing.

Style is how you see the world and how the world sees you. It isn’t today and it isn’t tomorrow; it isn’t a dress or a car or a shoe or a comment—it’s the cut of your sail as you cross this crazy, uncharted sea. Far ahead, legions of boats have already made the crossing—some grander, some more sleek—and still newer boats are always coming up behind you. Style is the manner in which you navigate your one remarkable voyage.

Arthur Elgort/Conde Nast Archive