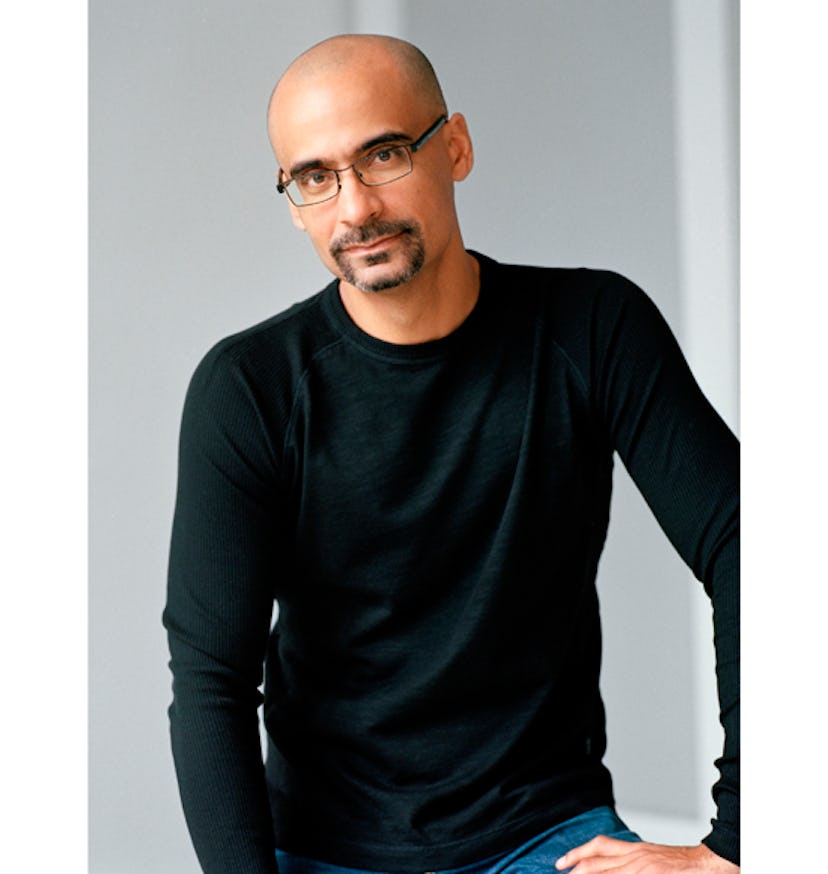

FIVE MINUTES WITH JUNOT DIAZ

Junot Diaz Like most of his characters, novelist Junot Diaz speaks in a machine-gun, rapid-fire cadence peppered with a frothy brew of hip-hop slang, comic book patois, literary theory and profane Spanglish—and what you quickly...

Like most of his characters, novelist Junot Diaz speaks in a machine-gun, rapid-fire cadence peppered with a frothy brew of hip-hop slang, comic book patois, literary theory and profane Spanglish—and what you quickly learn in print (or in person) is that the Diazian vernacular is one of genius. “When I think about what I do as an artist, I always come back to this very corny vision that I’m one of these people, like a lot of us, who’s lived in very strange and disparate worlds,” he explains while cataloguing his immigrant status as a “dirt poor” Dominican in Central Jersey, his status as resident leftie in a large military family, and his teaching “at fucking MIT,” where he spends time when he’s not performing the “frustrating like a motherfucker” tasks of penning Pulitzer-winning novels (his debut, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao) or critically acclaimed story collections (1997’s Drown), or its sixteen-years-in-the-making companion piece (This Is How You Lose Her, just out from Riverhead).

It seems like the Yunior character from Drown is growing up in This Is How You Lose Her. Was that always the idea? I was really interested in a character who grows up in a world of infidelity. How do they find love? How do they become a person capable of finding love? It was always supposed to be this corollary project to Drown, but it just took forever to finish.

How’d they all come together at this moment? It was a slow process. Every story helps to make an arch, so the next stone that’s needed to fit in the arch had to work perfectly—it had to be angled perfectly, weighted perfectly—otherwise the arch just falls to pieces. I’d finish one story, one part of the puzzle, and then I’d sit there for the next four or five years trying to write the next piece, trying to get it to fit perfectly so that this whole thing would come together. And I would write pieces that are too feeble, too manic, too wide, wrong voice—you know, something was off. It was as if each of the completed stories were incredible taskmasters on the next story. They were very formidable judges on what was coming next.

There are definite autobiographical hallmarks throughout your works. What kind of evolution in your own life does this book mirror? We all go through this maturation process—how do we endure intimacy? Where do we find the necessary courage to stand by a relationship, or to renounce a relationship when it’s not good for us? This is not shit that comes pre-packaged in a motherfucker—it’s not built into your DNA. This is something a lot of us have to wrestle with, and I just gave Yunior a more extreme and pronounced version of my own struggles. Yunior’s is very unique, though it has some resonance with mine—they share some understanding.

God bless you if you’re the kind of person who is awesome at relationships from the get-go, but me and my friends had a lot of bullshit that made it hard for us to make a go of it. A lot of my friends grew up with ideas about women that were incredibly unhelpful, and we wrestled with that shit—without wrestling with it, you’re going to just regurgitate what the culture told you, and what the culture told us was that women were cute and interesting and inferior and people that we didn’t have to take as seriously.

How do think your boys—or women, for that matter—will respond to the book? If there were a competition for the slowest readers, my boys would be in the winner’s circle at the international level, so we’re still in abeyance waiting the judges’ cards on some of this. I hope they connect to some of it and they see some of the struggles and feel there’s a human authenticity to it—and I’m hoping that women will recognize these flawed fools for familiar human beings so that they may know what we feel. The idea of literature is that we encounter these incomplete souls and imperfect people and they help us reflect on our own imperfections and our own humanity. You hope you’re provoking a wide range of emotions, but you’re hoping that the last thing that you’re provoking is some kind of ultimate judgment.

Women’s issues are obviously proving to be big during this election season—you seem to be enjoying one of those serendipitous moments where history collides with a book release. It’s interesting to think how art speaks to our own obfuscation and evasion in the discourse on women’s issues. The current campaign has done nothing but reveal how blatantly hostile one of our political parties is toward women and how indifferent another one of our political parties is toward women. It’s sort of extraordinary when you think of our postmodern, enlightened country how regressive our politics around women are.

We like to think certain types of people don’t exist, but they’re right there in front of us. I think we know in our hearts these people exist—many of us are them, and many of us know them and are related to them. We just don’t want to be honest. The charade is no longer working—people think they can dispel their anti-women platform by just denying it, but it’s no longer working. The value of Yunior and these characters isn’t in their extremity—it’s in their blatant honesty. We’re in a really interesting time. People don’t know how to deal with reality. The very people who are doing this don’t think they have a problem. The arrogance, the sense of perfection, is chilling.