The Horror and the Glory

In the small lobby of Blumhouse, Jason Blum’s multimedia production company, which specializes in minuscule-budget, big-concept, director-driven horror films, there is a wall-size painting hanging behind the two receptionists, done in the exaggerated comic book style of Roy Lichtenstein. Lichtenstein’s trademark dots have been replaced with tiny houses featuring the letters bh, and a blonde, clearly distressed beauty is pictured on the phone saying, “I just saw a Blumhouse film, and I won’t sleep for weeks.” The image perfectly sums up what Blum brings to the current landscape in Hollywood: a “royal” lineage (his father, Irving Blum, owner of the Ferus Gallery, was one of the most prominent art dealers of the ’60s—championing, among others, Andy Warhol, Frank Stella, and Lichtenstein) and, significantly, a Pop art–like approach to filmmaking.

Despite the fact that this cool midcentury office building, which Blumhouse owns, is in an unfashionable part of Koreatown, near downtown Los Angeles, Blum is currently, from a financial standpoint, the most successful producer in the mainstream movie business. In the past six years, he’s made 11 hit horror films—including the instant franchises Sinister, Insidious, and The Purge—for a combined $45 million (not including marketing costs) that have taken in more than $1.4 billion worldwide. Blum also produced Whiplash, an intense biopic about the war of wills between an aspiring jazz drummer and his sadistic teacher, which won the top prize at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival and is a strong Oscar contender. At a severe, belt-tightening time in the entertainment business, last July, Universal Pictures signed Blum to an almost unheard of 10-year deal.

“Here is our newest franchise,” Blum told me, standing next to a poster for Ouija set on a Now Playing stand in the lobby. In its first week of release, Ouija made almost $20 million. Blum, who always seems to have perfect bed-head hair, was wearing tan pants, a pink button-down shirt, striped socks, and a navy blazer. Although he’s 45, he radiates boyishness and bouncy enthusiasm, especially when talking about his work. “We like to call what we do ‘auteur filmmaking,’” he said, pointing to a lineup of framed portraits of Blumhouse directors, most of whom (like his close friend the actor Ethan Hawke) are not known for their work, or interest, in horror. This mix of class and mass reinforces Blum’s business model: Go big, pay little, and everyone profits both creatively and financially. “We give the directors more control than they usually have in Hollywood. When we have a director we’re trying to sign, I show them this wall of talent and then take them over here.” Blum walked to a spot where a framed mirror in the same rectangular shape as the portraits was hung. “I say, look here—this is our newest director,” he told me with a laugh. “It works about 50 percent of the time, which is good odds for this business.”

Six years ago, Blum was struggling. He had a producing deal at Paramount Studios, but he had yet to find the right creative niche. Was it big-budget action films? Or more indie-type dramas? “I longed to be mainstream,” Blum said, as he continued the tour through his offices. “And I pitched constantly and planned all the time, but I never got anything made. I finally ended up making the kid-friendly comedy Tooth Fairy, starring the Rock, at another studio, and I thought, Great—I finally get to make a studio film! But it wasn’t what I thought it would be like. In fact, I was miserable. Big studio productions just weren’t the right fit for me.”

And then everything changed: In 2007, an agent sent Blum Paranormal Activity, a home-movie-style horror film, as a sample of the director Oren Peli’s work. The movie, which cost only $15,000 to make, had been turned down by every distributor and was heading straight to video. But Blum saw potential in it. “I went nuts,” he said as he showed me his newly built screening room, where two people were adjusting the sound mix on the next sequel to Sinister. It was a two-year odyssey with Paranormal—“Paramount rejected it 100 times,” Blum said—but eventually the film broke every record, earning nearly $200 million worldwide.

Another producer might have leveraged the massive success of Paranormal to work on less genre-centric projects, but Blum recognized low-low-budget horror as an underappreciated corner of the movie business. “If you have a huge hit at 23, you think it’s all you and your brilliance,” Blum said. He was staring at a giant board where the progress of 17 upcoming Blumhouse movies in various stages was being tracked. “Luckily, I was nearly 40 when Paranormal happened. I knew it was the movie that guaranteed the success. I realized that I could follow this low-budget model and make it special.” Back then, Blum turned down opportunities to produce big-budget films—he still does. “Our idea model at Blumhouse is a movie that costs $4 million and change. If everything goes wrong at that price, you’re still okay financially. Even in today’s economy, you can always get $4 million out of a horror film: two for international and two for domestic. At that price, we get to play, do weird stuff, use new directors, and take chances. It’s bare-bones filmmaking. I always say to the actors in our movies, ‘On set, your trailer is the same size as mine—and I don’t have one.’”

I first met Jason Blum 15 years ago, when he was working for what was then Miramax. After graduating from Vassar in 1991, he co-ran acquisitions for Bob and Harvey Weinstein, scouting finished films, usually at festivals. At Cannes, he would rent a Vespa and navigate the perilous roads between the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc and the Palais du Cinéma, seeing movies and helping to close deals. Blum would champion art house films like The Others and Iranian features like Children of Heaven and then dash off on his scooter in full black tie. It all seemed very glamorous.

Last year in Cannes, however, Blum was nervous—he was there for Whiplash, which had been selected by the Directors’ Fortnight arm of the festival. While ostensibly a story of the clash between a pupil and his teacher, Whiplash is really about the passion it takes to be great. “If there’s a scary-movie version of an art house film, it would be Whiplash,” Blum told me in Cannes. “I don’t think it’s accidental that I was attracted to this project.”

And while, as a drama devoid of guts, gore, and paranormal activity, Whiplash does not seem to fit with Blum’s core brand, it does jibe with his personal history. Blum’s mother is an art historian who specializes in the Italian Renaissance; between her and his art dealer father, Jason, an only child, was around artists (and the artistic temperament) most of his life. (His middle name is Ferus, after his father’s pioneering Los Angeles gallery.) “All of them were in our home constantly: Claes Oldenburg, Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella, Lichtenstein,” Blum told me at his office when I visited. “Today, those artists are talked about like commodities, but then there was no money. I somehow absorbed that notion of striving for excellence for no reason other than it was what you were compelled to do.” Blum paused. “Neither of my parents likes horror films,” he said, laughing. “But my father loved Whiplash! It’s his favorite of all the movies I’ve done.”

In Cannes, Whiplash received a standing ovation and would become the underdog darling of the 2014 awards season. Last August, Blum won an Emmy for coproducing The Normal Heart, an HBO movie based on the Larry Kramer play about the AIDS epidemic. And yet, he squirmed when the suggestion was made that he was branching into “quality” projects. “One of the things I learned from my father is that you have to believe. No one believed in the Warhol Soup Cans or Roy Lichtenstein’s dot paintings, but my father always did. He built his career on believing in things that no one else believed in.”

Like his father, Blum is unorthodox. His office, for instance, is fairly small by Hollywood-mogul standards. He does not strive for opulence—quite the opposite, in fact. Two years ago, when Jason and his wife, Lauren Schuker, a television writer who once worked for The Wall Street Journal, went to Morocco on vacation, he balked at paying $22,000 for two first-class tickets. Instead, he purchased a row of coach seats for $1,800 and had a narrow, custom-made mattress built (cost: $500) that could be blown up into a makeshift bed. “I brought it on in my carry-on luggage,” Blum said proudly. “People were impressed.”

Ever efficient, he was, however, kidding (or at least I’d hoped he was) when he spoke about the benefits of the impending birth of his first child. “In horror films, you always need a demonic baby,” Blum said. “Scary movies are about vulnerabilities, and you’re most vulnerable where your kids are concerned. I’m very glad to have a child to put in my films; it will be so easy to cast.”

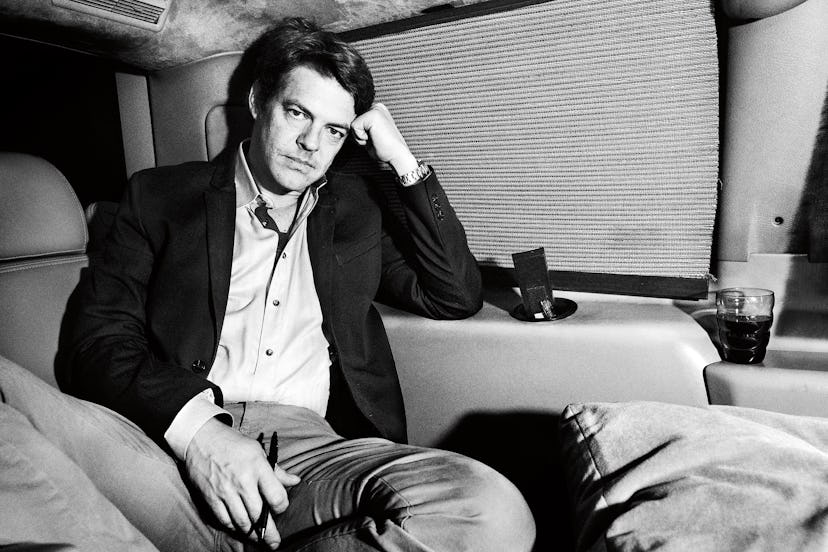

But Blum was definitely not joking when he took me outside to the parking lot to see what is, perhaps, his favorite innovation: his mobile office. Six years ago, he felt he was wasting valuable time driving around Los Angeles from meeting to meeting—so he transformed an old white Chevy Astro van into a kind of Blum Mobile. For $25,000, he had the seats ripped out and installed couches, a 36-inch flat-screen TV, and a blue carpet that reads BLUMHOUSE in script. “I sit here,” Blum said, stretching out on the plush green sofa, holding a keyboard embedded into a rectangular pillow. “I can check my emails, talk to the office, take care of all my business. I spend three to five hours a day on the road. Why waste time?”

When it’s not in service, the van is parked at Blum’s home in West Hollywood; he uses his own car only on weekends. “At first, everyone thought I was crazy to drive around in a van,” Blum told me. “But now they see the logic. It’s like that with everything I do: It may seem crazy, but it does all make sense.”

Back inside the Blumhouse offices, Blum led me up some stairs to the roof, which has been turned into an inviting deck, complete with picnic tables and plants, and pointed out two buildings nearby—one where Blumhouse does all its casting and the other, which the company just bought, that will soon house more employees. Like all of his projects, these buildings have a certain new cool-world sensibility: Blumhouse feels exciting, different, and entrepreneurial. The company—and its movies—succeeds in balancing a DIY indie spirit with the ability to reach a conventional, broad, studio-fueled audience. “I think you can do a commercial film at a low budget that has an independent feel,” Blum said, noting that there is actually a greater profit incentive for everyone involved: Hawke was not paid a premium to star in The Purge—a horror film with a $3 million budget about a future society that allows 12 hours of unpatrolled violence and mayhem every year to release the evil urges of its people—but he received $2 million of the film’s $91 million worldwide gross.

“Everyone talks about high/low all the time,” Blum said as we stood on the roof, the HOLLYWOOD sign in full view behind him. “And while I am interested in bringing the ‘high’ to these movies, I also like that horror films are ostracized in this town.” He looked at those iconic letters in the near distance. “I like to know Hollywood is out there,” he said, waving at the sign. “But I also like to know that it is still far enough away.”

Photos: The Horror and the Glory

Man with a van: Jason Blum in his mobile office, Los Angeles.

Nico, Irving Blum, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha (from left), and others, 1966. Photograph by Steve Schapiro/Corbis.

Blum (center), on the set of Sinister 2. Photograph by Elizabeth Sisson.

A still from Ouija. Photograph by Daniel McFadden/Universal/courtesy of Everett Collection.

Matt Bomer and Mark Ruffalo in The Normal Heart. Photograph by Matt Kennedy/Film District/courtesy of Everett Collection.

A still from Paranormal Activity. Photograph by Matt Kennedy/Film District/courtesy of Everett Collection.

J.K. Simmons in Whiplash. Photograph by Daniel McFadden/Sony Pictures Classics/Courtesy of Everett Collection.

On the set of Sinister 2. Photograph by Elizabeth Sisson.

Ethan Hawke and Blum traveling to actor Steve Zahn’s wedding, 1994. Courtesy of Jason Blum.

Still from The Purge. Photograph by Paramount Pictures/courtesy of Everett Collection.

Jason Blum and actress Rose Byrne at the premiere of Insidious: Chapter 2, 2013. Photograph by Kevin Winter/Getty Images.

Jason Blum (bottom, right) with the Malaparte Theater Company, 1994. Courtesy of Jason Blum.

Blum recently posted this photograph on WhoSay, tagging it: #tbt to when jason blum screamed during #purgebreakout. and guess what? #purgebreakout is baaaack in la for halloween season!. Courtesy of blum productions/whosay.

Warhol and Irving Blum in 1966—Blum ran the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, where Warhol first showed his Soup Cans. Photograph by Steve Schapiro/Corbis.