Louise’s Trip to the ER

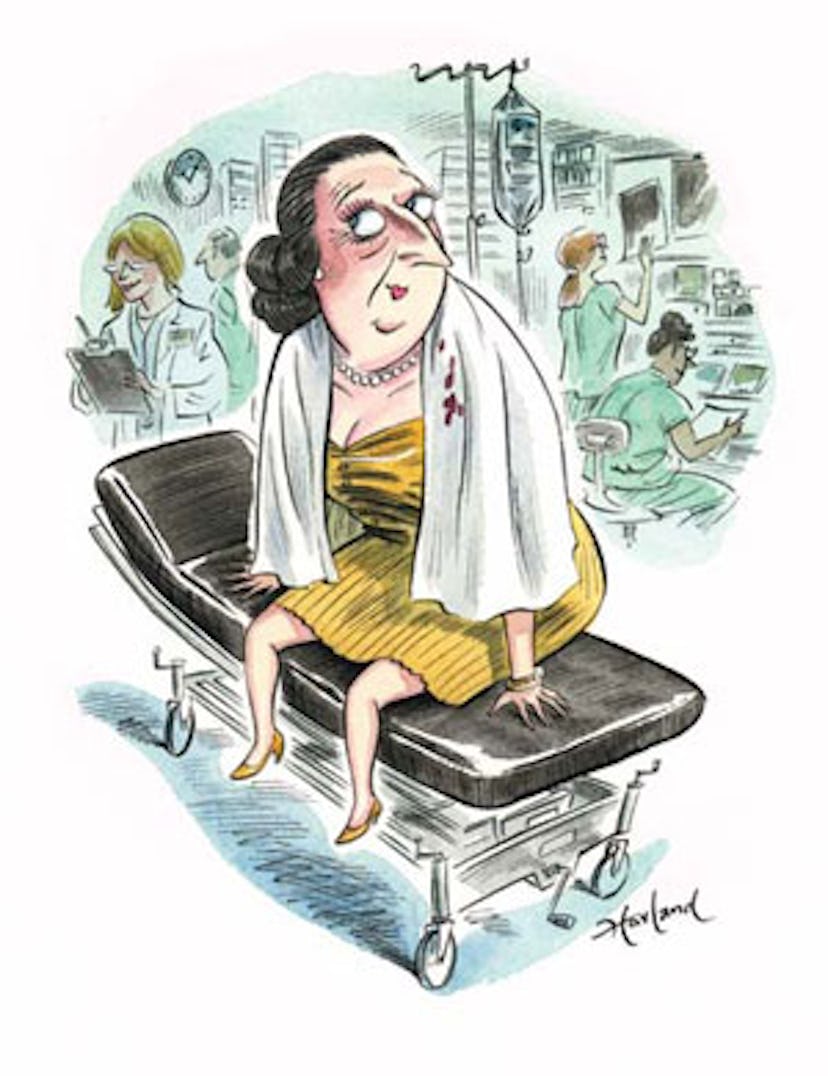

A nosebleed lands the Countess in a New York emergency room, where she considers our health care system.

As the health care bill slowly hemorrhages in Congress, I had some firsthand experience with hospitals recently, because I had to go to the emergency room with a little hemorrhage of my own.

Off I went to New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center on York Avenue, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. I arrived with a bloody bath sheet draped over my shoulders—not my favorite accessory, I assure you, but I needed something to catch the blood dripping from my nose (a friend suggested I get a red one, but I feared I’d look like a matador). I observed the scene around me. And what a fascinating scene it was. It was clean and orderly, and the staff was well turned out, at least by my fashion eye. The big thing was that, as usual in America, the emergency room workers had smiles on their faces most of the time. I’d arrived upset and anxious, but their manner put me at ease. This isn’t as bad as I expected, I thought.

The only problem was, there weren’t enough beds. They sat me on a gurney and told me to wait. So I decided to be patient. I waited. And waited. I waited seven hours, which was a bore, but at least I knew I would eventually be seen.

Finally I was moved to a curtained enclosure. I could hear the conversation next door, where a Greek man, obviously in shipping, was being looked at because he was having trouble walking. The doctors and staff were fascinated to know what he did. He said he owned several big oil tankers, then muttered, “And when I say big, I mean big.” A doctor asked, “How big is big? Do you have a large crew?”

The Greek tycoon didn’t answer. Jokingly, the doctor said, “We’d love to be invited on your tanker and see what it looks like.” It was another example of the incredibly friendly American spirit.

“Oh, of course,” the Greek man replied absentmindedly.

As for his treatment, I never found out.

In my case, there was an endless stream of chores. My blood pressure, which had already been taken, was taken again. An intriguing machine that could measure the oxygen in my blood was hooked to my finger. I was questioned about my health. A woman, tiny like a doll, came in and announced herself as a “physician’s assistant.” I didn’t know physicians had assistants. She looked up my nose and asked what doctor I had at the hospital. I told her I didn’t have one at the moment. “You don’t have an ENT?” she asked. Why would I? My condition had just started. She took my blood pressure again, and then said she would run some blood tests to make sure I could coagulate properly. Eventually I saw a doctor, who told me the bleeding was caused by the cold weather, which dries out the inside of the nose, making it crusty, which led to the bleeding.

I began to think about what would have happened had I been in my beloved Alps. The nearest emergency room is miles away, far down the mountain. A doctor would have made a house call to the schloss, but he wouldn’t have had the equipment the ER had—the MRI, the balloon up the nose to stop the bleeding, etc. I would have had to be helicoptered to Bern for all that.

As I waited and observed, I became focused on the idea that the more things change, the better off they would be staying the same. Perhaps Congress, and especially Nancy Pelosi—after she’d been to the hairdresser and was coiffed for the cameras—should see how well the emergency room works and the fact that whoever comes in is tended to, whether or not they can pay. The staff always remained solicitous and full of good cheer. (According to its annual report, the hospital’s emergency room had 231,162 visits in 2008, although I was told not to go on weekends and holidays, when things are a bit more chaotic than when I was there.)

Whatever happens with the health care bill—and whatever side of the debate you’re on—all I know is that a visit to an emergency room humbles a person and punches out all of one’s self-importance. You get a glimpse of humanity that many people hide from. Here are people smilingly and energetically trying their best to make you feel better no matter your condition. What can be better than that?