Olivier Saillard: Crusading Curator

Everything you need to know about the new director of the Galliera museum in Paris

Rummaging in his jacket pocket, the curator Olivier Saillard retrieves a small skinny rectangular piece of wood and rubs it for luck. “Touch wood!” he cries. “A friend gave this to me when I arrived here, and I’ve carried it with me ever since.”

“Here” is the Galliera museum, an ornate late-19th-century building in the blowsy neo-Renaissance style, opposite the Palais de Tokyo contemporary art center in Paris. Originally intended to house the art collection of a fabulously wealthy socialite, Maria, Duchess of Galliera, it has been home to the city’s fashion museum since the 1970s. But for nearly four years, the museum has been closed so that squads of specialists can restore its neo-classical columns, intricate domes, and mosaic floors.

Saillard, 46, took over as the museum’s director shortly after the restoration began and has been toting his lucky wooden charm in the hope that the work goes smoothly. So far so good: The newly named Palais Galliera is set to reopen in late September with “Alaïa,” the first exhibition of Azzedine Alaïa’s work ever to be held in Paris—and the prelude to Saillard’s crusade to reinvent a rather staid institution as a compelling museum devoted, in his words, “not to fashion but the sculpture of fashion.”

If anyone can pull it off, it’s him. To those seriously interested in fashion and its history, Saillard’s shows have been irresistible. In 2011 he exhibited the work of the mid-20th-century couturière Madame Grès in the Musée Bourdelle, which is dedicated to the turn-of-the-century sculptor Antoine Bourdelle. The contrast between Bourdelle’s rough-hewn classical figures and Grès’s intricately crafted garments made such an impression on the artist Nick Mauss that in his review of the show for Artforum, he noted that it “opened the door to understanding a practice of unmatched profundity and rigor—beyond the realm of fashion.” Saillard is relentlessly innovative in devising new ways to show old clothes, and last year, at the Palais de Tokyo, he coached Tilda Swinton on how to present more than 50 historic garments to a live audience without actually wearing any of them. Suzy Menkes, the fashion editor of the International Herald Tribune, wrote that the event was “timeless and exceptional,” and she described Saillard as “a rare combination of historian and showman.”

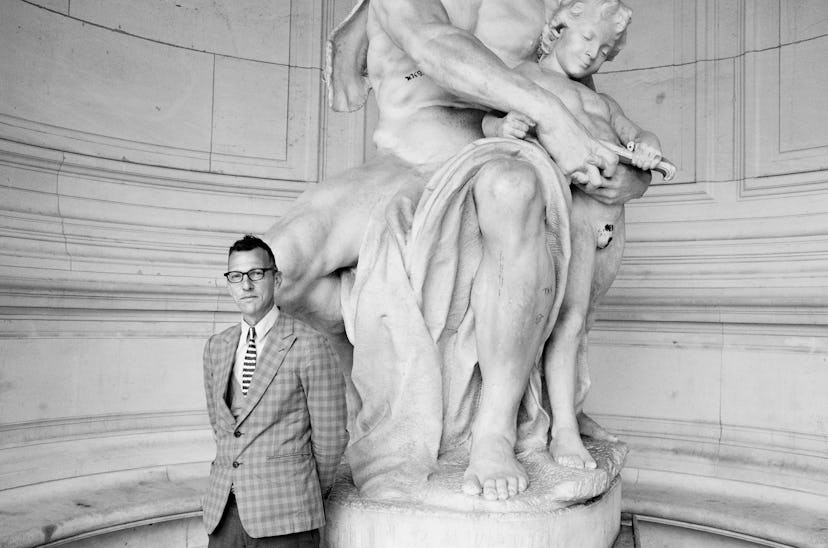

Slight in stature, with short-cropped dark hair and geeky glasses, Saillard looks like a schoolteacher, albeit one with a penchant for Dries Van Noten and Hermès. He is thoughtful, knowledgeable, and so bookish that he cheerfully spent every evening of the first half of this year reading five books a week to discharge his duties as a juror for a French literary prize.

Saillard was born “very far from the fashion world,” as he puts it, in Pontarlier, a small town in eastern France, where he was raised with four sisters and a brother; their parents were both taxi drivers. He spent much of his time in the attic, playing with or dozing on the family’s discarded clothes, and learned about fashion from his sisters. Despite dreaming of fashion school, he complied with his mother’s wish that he study art history. When he was called to military service, he persuaded the French army that, as a conscientious objector, he should do two years of civil service at the Musée de la Mode et du Textile, des Arts Décoratifs in Paris instead. “I was the first person to do military service in a fashion museum,” he chuckles.

The museum kept him on as an assistant curator until, at 27, he was offered the directorship of the tiny Musée de la Mode Marseille in southern France. Then, in 2002, he became the fashion curator at Paris’s Musée de la Mode. His ingenious analyses of Christian Lacroix’s designs for the theater and Andy Warhol’s relationship to fashion won rave reviews. After a short, unhappy stint at the then conservative Galliera, Saillard won a six-month residency in Japan in 2005, where he mostly wrote poetry. Later that year, he returned to the Musée de la Mode, where he continued his fashion experiments on a grander scale—most memorably, by filling two floors with a reconstruction of Yohji Yamamoto’s Tokyo headquarters. In every project, he combines visual spectacle with rigorous analysis of the clothing’s historical context. “Olivier infuses familiar topics with fresh insight,” observes Sonnet Stanfill, a curator in the fashion, textiles, and furniture department at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. “His knowledgeable enthusiasm is always infectious.”

In 2010, when the Galliera was looking for a director who could bring a new vision to the institution, Saillard seemed the obvious choice. He is now the custodian of one of the world’s finest fashion collections, with some 40,000 garments and 50,000 accessories dating back to the 1750s. There is a bodice that belonged to Marie Antoinette; one of Audrey Hepburn’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s dresses; and the entire wardrobe of Countess Elisabeth Greffulhe—an inspiration for the Duchesse de Guermantes in Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. He has also inherited the museum’s gloriously campy building, arriving just in time to modify the original restoration plans. “We’ve tried to reinvent the building exactly as it was in the 19th century,” he says.

So what will Saillard’s museum of “the sculpture of fashion” be like? For starters, it will delve deep into fashion history and explore different cultures. “I’m very excited about folkloric and ethnographic clothing,” he explains. “And la Greffulhe has introduced me to the fashion of the 19th century. It’s very sophisticated, very complex, with something modern.” He is planning an exhibition on his new crush’s wardrobe after “Alaïa” and a retrospective of ’50s fashion.

But don’t expect blockbusters. Saillard has taken on the Galliera at a time when there are more fashion exhibitions than ever but depressingly few that are not actually just crowd pullers for museums or promotional ploys for sponsors. “There are too many of them, and they’re killing something,” he says. The “new-old” Palais Galliera, as he calls it, will be calm and contemplative. It makes sense that one of his favorite places is the Chichu Art Museum, which shows a handful of works in a Tadao Ando building on Naoshima, a remote Japanese island.

“I want to create a museum where people have the space and time to think about what they are seeing,” Saillard says. “That’s the beauty of museums. You can spend all day there, knowing that no one will chase you away.”

Photo: Pierre Antoine