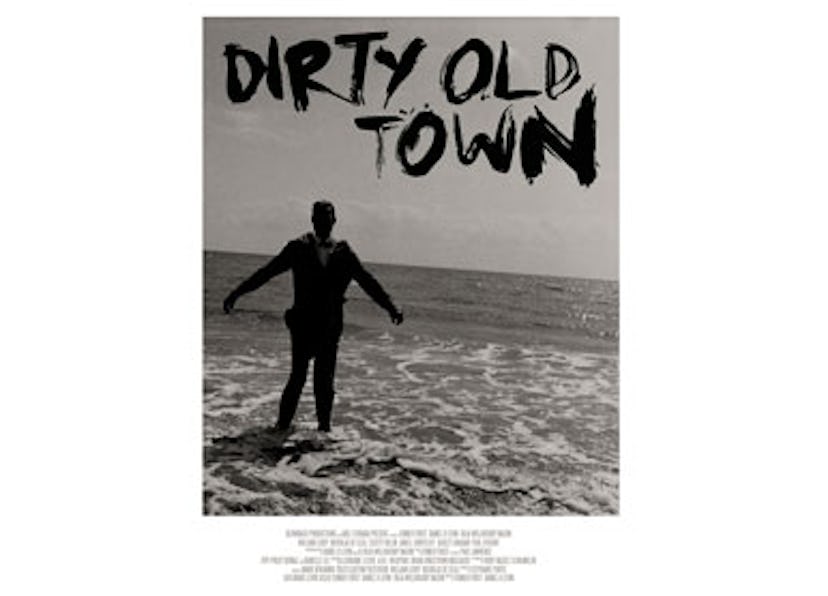

Preview: Dirty Old Town

Described by The New York Times in 2007 as “something of an Alamo, capturing the last of the [Bowery’s] wild, carnival spirit and the cavalcade of derelicts, drug dealers, artists, thugs and outlaws who once...

Described by The New York Times in 2007 as “something of an Alamo, capturing the last of the [Bowery’s] wild, carnival spirit and the cavalcade of derelicts, drug dealers, artists, thugs and outlaws who once roamed its streets,” Billy’s Antiques and Props, the iconic tented reliquary on the corner of Elizabeth and Houston Streets, oddly has incredible charm. Much of it stems from its owner, Billy Leroy, a cigar-chomping biker in three-piece suits who serves as the magnetic protagonist of the new dark comedy Dirty Old Town. Written by Daniel Levin, Jenner Furst, and Julia Willoughby Nason, and directed by Levin and Furst, the film is a fictional account of Leroy struggling to pay a landlord who’s threatening to turn the lot into a Starbucks. But plot is of little importance; it is the characters who drive the film—a rogues’ gallery of colorful kooks, played (often without script) by real-life New Yorkers like Paul Sevigny, Clayton Patterson, Nicholas (“Nicky D”) De Cegli, and Ronnie Sunshine. The result is a vibrant, visceral portrait of the streets of New York at their most sublime.

Daniel Levin: We had initially met a lot of the characters in Dirty Old Town while making Captured—including Billy Leroy. The idea was always to make a fictional narrative out of Billy and the characters that surround his tent of antiques. Our documentary experience came through by using real people in the film and at times letting things unfold naturally on camera. Julia Willoughby Nason: The decision to make a narrative film versus a documentary was to illuminate the fine line between real life and fantasy and run with it.

What was it like working with all these characters? DL: We cast certain characters like Billy and Ronnie Sunshine to basically play themselves. Ronnie is a total original. We could never script the words that came out of his mouth. When we started production we had a loose script, but a lot ended up being improv. Billy’s tent was an unusual central location—people would try to buy and sell him items while we were in the middle of shooting scenes. The fight between Billy and his daughter Celina was totally spontaneous. They had been fighting throughout the day while we where shooting other scenes, so we decided to incorporate it. Jenner took Celina aside and told her to vent her anger on camera. We threw them both in a tiny storage closet and the result was a classic father-daughter confrontation, which became one of my favorite scenes in the whole film. I think Celina used it as an opportunity to say some things to her father that she wouldn’t normally say. Jenner Furst: We threw Nicky D in a beat-up van and told him to drive while we filmed him talking to himself. He hadn’t driven in 20 years. He just smoked a joint and plowed through the streets yelling obscenities out the window and whispering sweet nothings to himself, oblivious to the fact that his driving was a serious threat to society and that our crew nearly fell out of the car countless times.

What was the most difficult aspect of making this film? JWN: Shooting 14-hour days, 20 days straight, in 100-degree heat and having a crew of 3 to 4 people. JF: Everything was extremely trying and difficult, and I’m not being cute. DL: We made a film with no budget, no permits, on the streets of New York City during the height of the summer. The unpredictability and insanity was a major stress at times. But what made it so difficult is also what makes the film so successful.

This is a very cultish New York film, in the tradition of Abel Ferrara. What films/filmmakers inspired you? JWN: Meat (Frederick Wiseman), Live Flesh (Pedro Almodóvar), Minnie and Moskowitz (John Cassavetes), The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (Werner Herzog). JF: Cassavetes and Altman were directors that personally inspired me. Woody Allen and Abel did too. This film actually takes a lot from Fellini’s playbook but ultimately it took on such a life of its own that it broke free of any previous dogmas like a reckless mutt digging through your kitchen trash can. DF: A lot of classic New York films inspire me—Abel, of course, with King of New York and Bad Lieutenant. We tried to capture that New York grime and underbelly. On the other hand, neo-realist directors like Federico Fellini were also a major influence. I think we tried to contrast the fantasy and beauty of Felini’s films with the grit of the New York City streets.

Leroy’s recent subway sign debacle—in which the police confiscated 100 of his subway signs, claiming they were stolen, and then gave most of them back when threatened with a lawsuit—could have been a subplot in the film. DL: The subway signs are in the film. We shot a larger scene about them but it got trimmed. If you watch closely there are a lot of subtle references to that story. More importantly the idea of Billy getting shady items from questionable sources, which is a major plot in the film.

You guys were snubbed from the New York film festivals. Any theories as to why? DL: I think the major New York festivals are moving more towards Hollywood and international projects. That is not necessarily a bad thing, but can leave local talent out of the game. We have taken the film to Paris and London on our own and have connected with audiences there and we will continue to do so worldwide festivals or not.

Dirty Old Town will premiere in New York at BAMcinematek on Wednesday, May 25 at 4:30pm, 6:50pm, 9:30pm with a filmmaker Q&A. For tickets visit bam.org

Above, the film’s trailer. For more on the film visit dirtyoldtownmovie.com

Photos by Julia Willoughby Nason