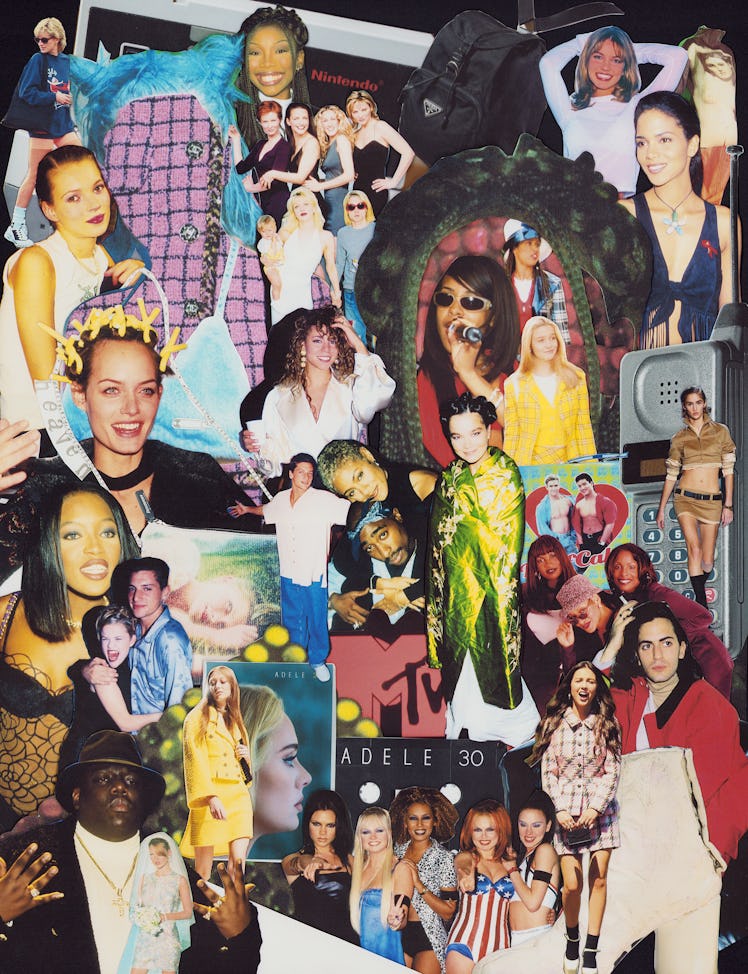

Call it the Zuckerberg paradox: The more the 21st century is dominated by smart devices and social media, the more there is a collective longing for the 1990s, the decade that trumpeted the end of the millennium and marked the final gasp of a global culture about to be completely rewired by Big Tech. Everywhere you look, across music, fashion, film, and television, there seems to be a postmodern pining for a less plugged-in era.

Few in the public eye wish they could turn back time as much as Adele, one of the music industry’s last remaining recording artists with a capital R. For the release of her latest album, 30, the singer persuaded Spotify to disable the shuffle button on all artists’ album pages, so that tracks would play in the chronological order of a vinyl record or CD. “This was the only request I had in our ever changing industry!” the singer tweeted. “We don’t create albums with so much care and thought into our track listing for no reason.” To drive home her point, she sells cassette tape versions of 30 on her official website.

Victoria Christina Hesketh, better known by her stage name, Little Boots, takes a similar approach. Hesketh, who, like Adele, is in her 30s, said her latest electro-pop single, “Landline,” is an ode to “being a teenager in the ’90s, when you would spend hours clogging up the family phone line to talk to your school boyfriend or girlfriends.” The slinky disco track came about during lockdown, when she and her friends were “doing quizzes and Zoom dance parties, and it reminded me how we used to cope before the Internet and computers,” she said. “The ’90s are like a warm, fuzzy sweater we can put on and feel reassured.”

Like music, fashion has always looked back to move forward. This season, cargo pants and carpenter jeans appeared at Missoni; the idea of underwear as outerwear was revisited by Prada; and Miu Miu showed exaggeratedly cropped, cable-knit sweaters and low-rise, teeny-tiny khaki miniskirts with brown belts that called to mind turn-of-the-millennium teenybopper naughtiness. At Chanel, designer Virginie Viard, who staged her show with an old-school elevated runway, went for accessory-laden leotards and jaw-length bobs, echoing house signatures from 30 years prior. The then-meets-now mood was reinforced by the choice of Christine and the Queens’ cover of “Freedom,” George Michael’s huge ’90s hit, for the soundtrack.

A look from Miu Miu spring 2022.

The trend is not limited to the runways. “Reinvention and Restlessness: Fashion in the Nineties,” an exhibition of Maison Martin Margiela’s hoof-shaped Tabi boots, Prada’s minimalist nylon backpacks, and other decade-defining high fashion, is on view through April at the Museum at FIT, in New York. “The World of Anna Sui,” a survey of the designer’s hippie-grunge staples and her inspirations from the era (think qipao dresses and Nirvana), is showing at the Mint Museum Randolph, in Charlotte, North Carolina, through May. “I’ve heard a lot of people comment that you could wear the clothes today, because they don’t seem like they’re from another period. That, to me, is a huge compliment,” Sui said. “People are missing the realness of that era, and how it wasn’t yet a manufactured or corporate thing.”

Naomi Campbell (left) and Anna Sui (center) during the designer’s fashion show on November 1, 1995.

Ava Nirui, the art director of Marc Jacobs’s Heaven line, which takes inspiration from Sofia Coppola’s 1999 indie opus, The Virgin Suicides, agreed. “The younger generation definitely romanticizes a time before the Internet,” she said. “The ’90s were the most ‘advanced’ pre-Web era in terms of culture, which is why it might seem so appealing to those who didn’t experience it.” Revisiting favorite moments of the past can also offer opportunities for thoughtful reexamination. As Colleen Hill, the curator of the FIT exhibition, combed through the museum’s permanent collection for a section of the show devoted to the “global wardrobe” (a term Hill said she cribbed from an early-’90s issue of i-D magazine), she encountered thorny threads to unspool. “The tricky thing is that many ’90s designs would be considered cultural appropriation by today’s standards,” she said. “Trying to navigate how a Chinese dragon on a Todd Oldham dress was viewed then, versus how it would be viewed now, is not an easy thing to do, but I thought it was really important to at least try to have that conversation in the exhibition.”

Simon Rex during a 1997 Tommy Hilfiger party.

At times, however, the ceaseless nostalgia feedback loop can feel more mind-numbing than eye-opening. Simon Rex, the ’90s adult-film twunk turned MTV VJ heartthrob, may be earning Oscar buzz at the age of 47 for his portrayal of a washed-up porn star in Red Rocket, but does the world really need Carrie, Miranda, and Charlotte pounding the Manhattan pavement, sans Samantha, in the Sex and the City sequel And Just Like That…? Queens, the ABC musical drama, stars Brandy Norwood; can it be a coincidence that her mid-’90s UPN sitcom, Moesha, was recently picked up by Netflix, and that her 1997 TV musical film, Cinderella, with Whitney Houston, is now available on Disney+? Then there is Twentysomethings: Austin, a new reality series billing itself as the true story of eight 20-somethings who set out to find success in life and love, while sharing a bachelor pad in Austin, Texas—or, as one Twitter user joked, “Not someone pitching The Real World to Netflix and getting it greenlit.” At least the creators of Peacock’s Saved by the Bell redux appear to be a little more self-aware. “That’s why we have all these reboots of teen shows from the ’90s. Get a new idea, Hollywood,” a character quips during an episode from the show’s current, second season.

It is an inescapable reality that nowadays, whether in film, music, television, or tech, those corporate behemoths that Sui said were not pervasive in her heyday are the ones churning out more and more tokens of ’90s faux-thenticity. Nintendo now offers a paid subscription upgrade to its popular Switch Online console, giving users the chance to play classic games from Sega Genesis and Nintendo 64, like Ecco the Dolphin, from 1992, and Mario Kart 64, from 1996. Amazon has its very own “90s throwback” section, complete with Smashing Pumpkins double CDs and enzyme-washed replicas of original Aaliyah commemorative merchandise. Even Hasbro makes “grown-up” Play-Doh packs engineered to evoke the buttery popcorn smells ubiquitous at Blockbuster video stores in the ’90s.

Aaliyah performs at KMEL Summer Jam, 1997.

Makeovers are often more successful in the hands of Generation Z. For her debut album, Sour, the 18-year-old pop powerhouse Olivia Rodrigo has used imagery that oscillates between the Total Request Live sensuality of Britney Spears during her 1999 ...Baby One More Time ascent and Courtney Love’s punk-prom aesthetic from Hole’s seminal 1994 album, Live Through This. On a personal level, the singer has been serving leggy luxury straight out of Cher Horowitz’s wardrobe in Clueless; think of her Instagram selfies in body-hugging plaid babydoll dresses, or her much-publicized visit to the White House last July, in a vintage Chanel spring 1995 tweed suit.

Arbiters of cool from the past represent “individuality, personal expression, and subcultures that were demonized by adults in their day,” said the fashion and culture researcher James Abraham, who created @90sanxiety, an Instagram handle that has amassed more than 2 million followers with its meticulously curated feed overflowing with everything from an early Xanax advertisement to stills of Halle Berry from the 1997 camp classic B.A.P.S. It’s also significant that icons from that period, like Kurt Cobain and Debut-era Björk, were exempt from participating in the endless slog of daily content that is the norm today. Abraham pointed out that “there are only X number of photos of Kate Moss that exist from, say, 1993.” That, he said, makes them seem rare and “very pure, in a way.”

The big business of a vintage vantage point is not lost on Abraham, who has given branding lectures at business schools and consulted for Nike. “Everyone is cycling back to things that they might have seen or done, because they are safe and tested,” he said. This is a foolproof formula for analytics addicts, whether they are Instagram archivists or Amazon chief executives. What the moody remix of Madonna’s 1998 ballad “Frozen,” which went viral on TikTok last year, has in common with the resale market for the classic Range Rover LSE from 1993 is that both are fueled by our shared memory bank. The end goal for companies and creators alike is to “tap into an existing audience,” Abraham explained, and capitalize on “the success of the original.”

There is no doubt that this endless retro stream offers an escape to a time when a car phone was a rare luxury. But the very persistence and pervasiveness of today’s mass nostalgia is only possible, of course, thanks to the algorithmic engines driving TikTok, Netflix, and other Big Tech platforms—in other words, the very same online tar pits we dream of escaping. To quote ’90s icon Alanis Morissette—currently the subject of Jagged, a new HBO Max documentary—isn’t it ironic?

Heaven bag with chain: Courtesy of Marc Jacobs; Adele cassette: Columbia records; Prada backpack, Maison Margiela Tabi boots, Pleats Please Issey Miyake dress: The Museum at FIT; all others: Getty Images.

Get the Look

This article was originally published on