Alexander Iolas, a Greek ballet dancer turned art dealer, once had an idea that seemed mad: he wanted Andy Warhol to reimagine Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper” for the Palazzo delle Stelline refectory in Milan, directly across the street from da Vinci’s original masterpiece. Of course, Warhol accepted.

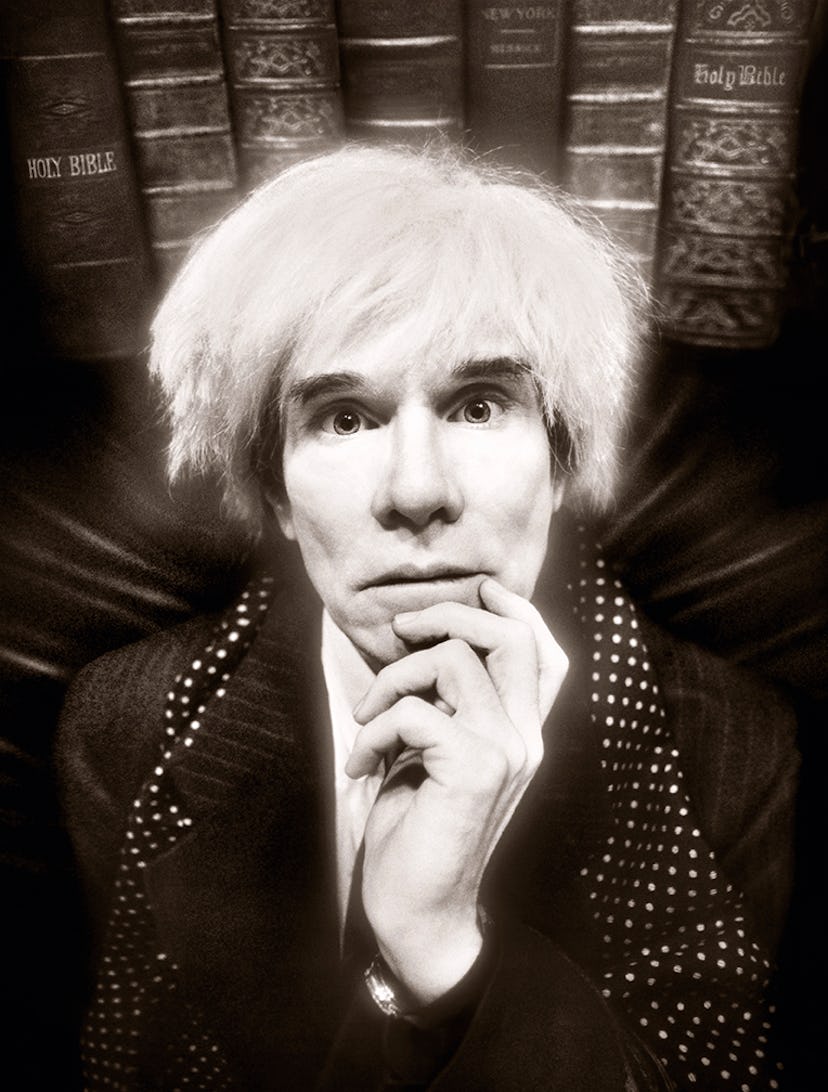

The Last Supper (1986) featured 22 of over 100 works Warhol had created under the commission: an excédent outturn from an artist consumed by his, then unknown, last assignment. He’d enlist Jean-Michel Basquiat for a collaboration, screen-print “Last Supper” replicas in neon yellow and hot pink, and in the end, he’d wear a spectacular silver wig to the opening. One month later, he’d unexpectedly die from gallbladder surgery complications.

Not to be mistaken as satirical or impish, The Last Supper’s exhaustive catalog reflected Warhol’s obfuscated relationship with the Catholic church. At his funeral weeks later, eulogist John Richardson revealed Warhol attended Mass multiple times a week, “was responsible for at least one conversion,” and “took considerable pride in financing [his] nephew’s studies for the priesthood.” Some funeral attendees were shocked, others not so much—when it came to Andy, whimsical contradictions were par for the course. A full Memorial Mass ensued, where Velvet Underground’s Lou Reed sang. Afterward, the funeral procession, which included Roy Lichtenstein, David Hockney, Fran Lebowitz, and Calvin Klein, would exit St. Patrick’s Cathedral and head to Diamond Horseshoe Nightclub. Few funerals so aptly represent the deceased.

At the Brooklyn Museum, Andy Warhol: Revelation recasts the icon through a personal religious lens. Curated by José Carlos Diaz and organized by Carmen Hermo, and on view from November 19, 2021 to June 19, 2022, Revelation has parsed out Warhol’s spiritual depth and duality with exacting finesse—acting more as a biography than retrospective. The editing skills of both Diaz and Hermo provide a concise throughline for viewers to follow, with unexpected eurekas dabbled throughout, revealing troves of potential (and joyful) rabbit holes. By the time you leave, it seems comical that Warhol’s religious affinity isn’t already common knowledge.

Revelation’s seven interconnected sections progressively build the exhibition’s thesis—taking us through a journey that begins and ends in Pittsburgh, just like Warhol himself. Through “Immigrant Roots and Religion,” Diaz and Hermo distance the viewer from “The Factory Andy” and introduce us to Andrew Warhola, son of devout Catholic and Polish immigrant Julia Warhola. His mother’s influence is apparent in both subject matter and style throughout the exhibit—herself an exceptional doodler, often depicting angels and cats, which are featured upon entry and stylistically revisited through Warhol’s graphite drawings. The childhood ephemera, including a baptism certificate, assorted crosses, and a painted figurine, add texture and tangibility to Warhol’s religious upbringing. It is a deft curatorial choice that breaks up a predominantly print and painting-based exhibition, helping to cleverly distinguish this period as both exit and entry point.

Walking through, “Madonna and Magdalen: Warhol and Women” operates as the most poignant module. A queer male from a conservative Ruska Dolina neighborhood, Warhol’s fascination with women often vacillated between matriarchal (old Italian, ma “my” + donna “lady”) and muse (Magdalen). His series of both Jackie Kennedy Onassis and Marilyn Monroe portraits face one another in opposition, operating as their respective roles of mother and lost lamb. Once standing between the two, the line separating the typecasts becomes gently porous through a mirrored somberness between the two series. From there, the exhibit bleeds into The Madonna and Child collection, which spans three decades and many mediums—the “odd” breastfeeding photographs slickly featured within a direct eye-line of Warhola’s kitchen sketches. The series, which includes nude photographs and gilded drawings, would eventually be abandoned when Warhol determined people wouldn’t understand—a conviction that seems partially inspired by his offbeat living arrangements with his mother. (After a day at The Factory, the artist would often return home to Julia, say a prayer, and go to bed.)

Section III, “The Renaissance Spirit,” relies more on wall text to explain Hermo and Diaz’s thought process, providing amusing anecdotes and tidbits of synchronicity that are less overtly religious. This reliance is dittoed in “The Catholic Body,” which mixes Warhol’s sexual exploration and desires in contrast to the gospel’s teachings. The “lewd” graphite depictions of genitalia wrapped in roses, semen-splattered fabric, and stapled flesh operate as an examination of his bodily desires—though any direct Catholic reference is a bit muddled without context.

The stars of the exhibit are loud and large, like Warhol himself: a room with two massive “The Last Supper” screenprints, a bevy of Basquiat boxing bags depicting the messiah’s last hurrah, and the unfinished Warhol film ****(Four Stars) commissioned by the Catholic church. The showstoppers nail the thesis home, providing ample opportunity and space to reflect. If you’re interested in kicking yourself due to art-history ignorance (as I was), the Brooklyn Museum makes sure there is enough square footage to do so.

When approaching the final modules, including “The Material World: What We Worship,” the exhibition transitions from reassessing Warhol to assessing modern-day society. “Material World,” touches upon the artist’s most well-known study: God as commercialism, a bungled Nietzschean experiment that spreads as we move towards 2-D value exchange, where we worship aesthetics and our “vibes” are a commodity.

Ironically, this brings up an interesting position for the Catholic church. For Diaz and Hermo, though they may no longer practice Catholicism, like Warhol, the church’s theatricality informed their understanding of visual culture. The incense, the velvet, and gilded saints are all a vibe. As Diaz mentions, as a child he “loved the drama of it all.” He’s not alone.

While Catholicism’s religious relevance has decreased rapidly due to a larger demographic shift to secularism, Catholicism’s aesthetic stock is doing fine. In 2018, The Metropolitan Museum of Art hosted the Met Gala’s Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination show, where Zendaya arrived as Joan of Arc, Ariana Grande wore a Sistine Chapel gown, and Rihanna arrived as The fucking Pope. The Wall Street Journal called it a “a gift from the sartorial gods,” while New York magazine declared it “gorgeous, moving, and surprisingly witty.” In today’s age, we are less god-fearing and more god-accessorizing, besotted with an institutional aesthetic that at one point held dominion over global social discourse. The church—the modern western world's first superpower—is now so kitschy it makes for a good character anecdote within HBO’s version of blue-collar America. Its appeal is rampant within Hollywood hipster theory which repackages all things satirical and wayward for dramatic flair—and what could be more ironic than a rusted iron fist?

This brings the title of the exhibition Revelation into focus, not only revealing an unhidden truth, but also the difference between Warhol and today’s artistic usage of the Catholic church. A man who had no intention of using the church as a punchline made a career of tongue-in-cheek social critique. And while Warhol’s career celebrated hypervisibility, the public has willingly cast a blind eye towards his unwavering religious devotion, as though we cannot process that the Queer King of Plastic could contain such multiplicities. This is where the exhibition shines, because once in front of the evidence, it’s silly to not have made the connection on one's own accord.

This article was originally published on