Candyman’s Creators & Cast Reflect on Bringing the Classic Into 2021

You may already be familiar with the legend of Candyman: say his name five times in the mirror, and he appears behind you to commit a grisly murder. But what are his motivations for killing, and why does he need to be evoked through such specific nomenclature? That’s what Nia DaCosta’s version of Candyman, which comes out in theaters today, tries to figure out.

When Bernard Rose’s Candyman was released in 1992, the film was told from the point of view of Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen, who appears in the 2021 film in a different role), a nosy grad student investigating folklore, superstitions, and urban legends, while also poking her nose around Chicago’s Cabrini-Green housing projects. She is subsumed within the legend of Candyman, a mysterious figure who haunts the neighborhood with his hook for a hand and razorblades in candy, taunting those who say his name five times in the mirror.

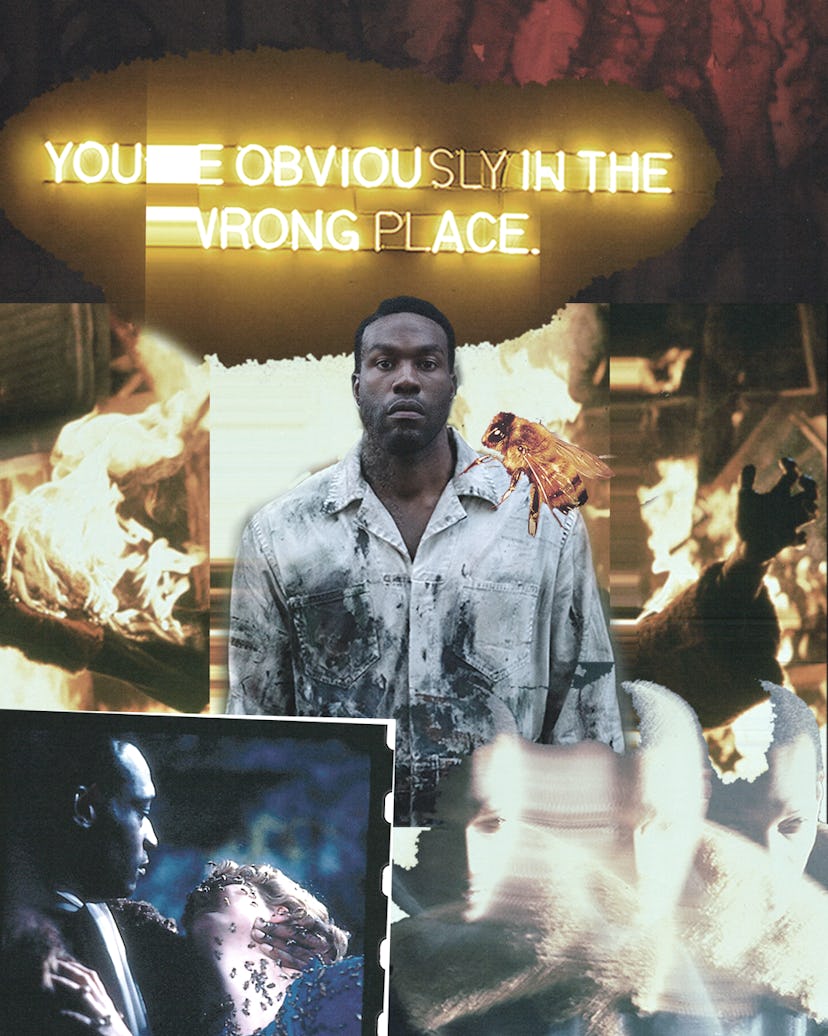

DaCosta’s “spiritual sequel” to Candyman, co-written with Win Rosenfeld and Jordan Peele, and starring Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, Teyonah Parris, Colman Domingo, and Nathan Stewart-Jarrett is more intentional about its use of folklore and oral history as a framework for tracing the systemic violence and trauma inflicted on Black Americans, and telling the story from a Black person’s point of view.

One branch of the film’s thesis statement is its analysis of oral histories as a narrative device, and the importance of that device in Black culture, which has existed for centuries. The main character, Anthony (Abdul-Mateen II), is a visual artist who attempts to address the same issues within his work (his “Say My Name” mirror art piece that is shown in the beginning of the film particularly stands out as a metaphor for holding a mirror up to society). “Jordan and Nia wanted to make a shift from the original where there’s not just one Black man in 1890 that was wronged,” the film’s producer, Ian Cooper, said.

“This happens in perpetuity, and in multiplicity, and has been happening for forever. That horrifying conceit echoes the very notion of an urban legend, which is a perpetuation of a story wherein the ingredients are subject to the teller and the listener’s sets of experiences,” he went on. “A kid telling a story about 1978 in Cabrini-Green is a different shared experience for the teller and listener than someone from any other moment in time. The notion that Candyman manifests in the form of another unwilling Black male cultural martyr felt like the only conceptually honorable way to approach a sequel.”

One of the few actors from the first Candyman film who returns for DaCosta’s version is Vanessa Estelle Williams, who plays Anne-Marie. In 1992, she played the young mother whose dog is killed and baby is taken by Candyman, whom Helen Lyle saves by sacrificing herself. Nearly three decades later, Candyman is looking for that baby, who, in the logic of the film, must become the next iteration of the “villain.” It turns out, the Anthony we see, all grown up and eager to make a statement in the art world, is the same baby whom Candyman has come back to claim. In trying to find his voice with his art, Anthony steps into his fate. “The history of our trauma as Black people in this country is the most disturbing, chilling, bloodcurdling theme in the movie,” Williams told W before the film’s release. “Candyman is how we deal with the fact that these things happened, and that they’re still happening,” Domingo’s character (a morally dubious man named Burke who operates a laundromat near the torn-down housing project) utters near the end of the film. It becomes clear that this urban legend has been utilized as a coping mechanism for an entire community.

Many of those involved in making the latest iteration of the film watched the first Candyman when they were way too young. “I was very small, maybe five or six years old, and I remember the iconic silhouettes of the film. My very first experience with the character of Candyman was me and my siblings messing around in the bathroom, playing the game in the mirror and daring each other to say it,” Abdul-Mateen II told W last year, when the film was originally supposed to hit theaters. “When I was growing up, Candyman was just a monster; a supernatural, evil ghost,” the actor went on. “Later on, I had more sympathy for that character, and understood the involuntary history of him becoming Candyman.”

Producer and co-writer Win Rosenfeld echoed the sentiment. When he and Peele started Monkeypaw Productions, the studio that produced Get Out, they had already been thinking about revisiting Candyman for years. “Jordan and I have been fans of Candyman for forever. As horror movie kids, it really stood out because it felt so elevated and nuanced and elegant in contrast to other supernatural slashers at the time,” he said to W. “The feeling from that original Candyman was that it was a horror movie that had all of the scares and visceral emotion, and yet it also felt deep.”

DaCosta’s film also takes a stab at the 1992 version’s illustration of Black men being positioned as scapegoats for crimes they did not commit in American culture. The character of Daniel Robitaille is revealed as the “original” Candyman, a portrait artist in the 1800s whose hand was cut off, body smeared in honey for bees to sting him, then burned to death by a white lynch mob after they discovered his affair with a young white woman. He then seeks new incarnation to take his place. “It was poignant for me because I have two sons who are artists,” Williams said. “I could pull from my own life, and it was thrilling to resurrect Anne-Marie and think of how she’s lived with the secrets she’s kept from her son.”

Another element of the original Candyman that DaCosta’s film attempts to refresh is its analysis of gentrification. The film was shot on location in Chicago, and tries to draw a parallel between one systemic issue and another, as is demonstrated by the conversation between a white art critic and Anthony at his show’s opening in the West Loop neighborhood.

“There’s no time where this film’s content is irrelevant, sadly, because of this never-ending cycle of violence in this country,” Cooper said. “It can be retrospective and contemplative for this recent moment in our history and hopefully perpetuate a continual thoughtfulness around that movement. This shift in culture is one to be in constant vigilance about, and not just a moment.”

Many of those involved in the film, whether they be actors, producers, or writers, have commented on its timeliness. The pandemic put Candyman on hold in 2020, and pushed its release date over a year. “It’s hard to say what the impact might have been, had George Floyd not been killed or if any of the events in the last 18 months had not happened, but I like to think that we as a culture are evolving,” Williams said. “These aren’t new stories. It would have been and will be impactful, because these are timeless themes and issues.”

“There are obvious reasons why the film is timely, but it’s also a film that is commenting on this sometimes false notion of timeliness,” Rosenfeld said. “There has always been a problem. News can come and go, and things can become in vogue, you can gentrify Cabrini-Green, or hang a portrait in a gallery and sell it for $100,000. But that doesn’t change the underlying pain and injustice that sits at the root of American society.”