Francesco Vezzoli on Political Art, Netflix, and His Provocative New Exhibit “TV 70”

A chat with the Italian artist on the occasion of his new exhibition “TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli Watches RAI” at the Fondazione Prada in Milan.

The Italian artist Francesco Vezzoli, who might be described as a gloriously lapsed Catholic, has knelt for some time now at the altar of celebrity. And he’s done that, like he does most things, with knowing insouciance. When he convinced Roman Polanski, Michelle Williams, and Natalie Portman to come together to make a 2009 commercial for a fake perfume directed by Polanski and starring Williams and Portman, he had his friend and unfailing supporter Miuccia Prada designed the fragrance, which was to be called Greed.

As you watched these two movie stars (neither of whom endorsed fragrances at the time) struggling unbecomingly and eventually clawing at each other to get to the prize bottle labeled “Greed,” it was hard not to get it: This was a really expensive, high-production value way to tell us something about our insatiable appetite for celebrity.

But for such arch commentary to be effective, it needs an agreed-upon collective understanding of reality to dance frothily over. And Vezzoli knows that today’s political reality is anything but recognizable. “I think artists feel completely defeated,” he said on the phone from Milan, where he recently opened his exhibition “TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli Watches RAI,” an examination of television, art, and culture in Italy in the 70s, at the Fondazione Prada.

Mario Schifano, Paesaggio TV, 1970.

“Politics, in its unpredictability, has truly surpassed art,” Vezzoli went on. “Imagine being a screenwriter of House of Cards. I would fire myself!”

By now, it’s a tired industry joke: House of Cards is Washington, D.C.’s idea of itself, and Veep shows D.C. as it is. But these two outlandish TV shows conceived in the Obama era have found themselves chasing reality’s tail in the Trump era, and barely being able to keep up with the current administration in terms of, well, outlandishness.

Vezzoli feels artists are struggling with the same problems.

“I’ve seen more political art in moments of history where there weren’t such politically dramatic changes,” he said. “Right now, history is the surreal artwork.”

Carla Accardi, Grande trasparente, 1975.

While a few instances of current protest art have thrown and landed a punch, it does feel to many observers in the art world, including Vezzoli, that artists are struggling to find their footing in a tumultuous time. It could explain, also, why “TV 70” is largely a curatorial endeavor (Vezzoli’s only new work in the show is a montage of news clips from the era), and an exploration of a decade full of its own political turmoil when the only TV on TV was produced by the state.

And yet RAI, the state broadcaster, still somehow made room for the mercurial talents of risk-taking Italian filmmakers like Bernardo Bertolucci and Roberto Rossellini, who directed miniseries, and Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, who made films for TV that would go on to win prizes at Cannes. When Vezzoli got home from school, he turned on the TV to find not cartoons but avant-garde theater.

“The output on TV was incredibly intellectual, and there are now two or three generations of Italians who are extremely well-prepared culturally,” Vezzoli said. “I have a childhood memory of this show hosted by Mina and Rafaella Carrà. Like America, we had our male TV hosts like Johnny Carson. But all of a sudden there was this show that is these two women. It’s only them—they host it, they run it, they sing, they dance. The only men are the guests.” He laughed. “And then there are several drag acts as well.”

Carrà in an episode of Canzonissima, 1971.

Unlike America’s era of peak TV, where there is everything for everyone, Vezzoli, who called Netflix “the biggest art producer in terms of images” (in a purposefully provocative way), wanted his exhibition, which also features the work of artists like Carla Accardi who confronted the Italy of that era, to recall a time when there was a shared collective memory, when it was possible to produce culture not for your audience, but for an audience of literally everyone—and to do it in an intellectually stimulating way that didn’t pander.

It’s a mission that seems almost inconceivable now in America in the age of cable news.

“Most of the Americans I’ve taken though the show, the comment I’ve heard from them is, ‘We could never had something this forward, this daring on our mainstream channels,'” Vezzoli said. “And that’s when I get really proud.”

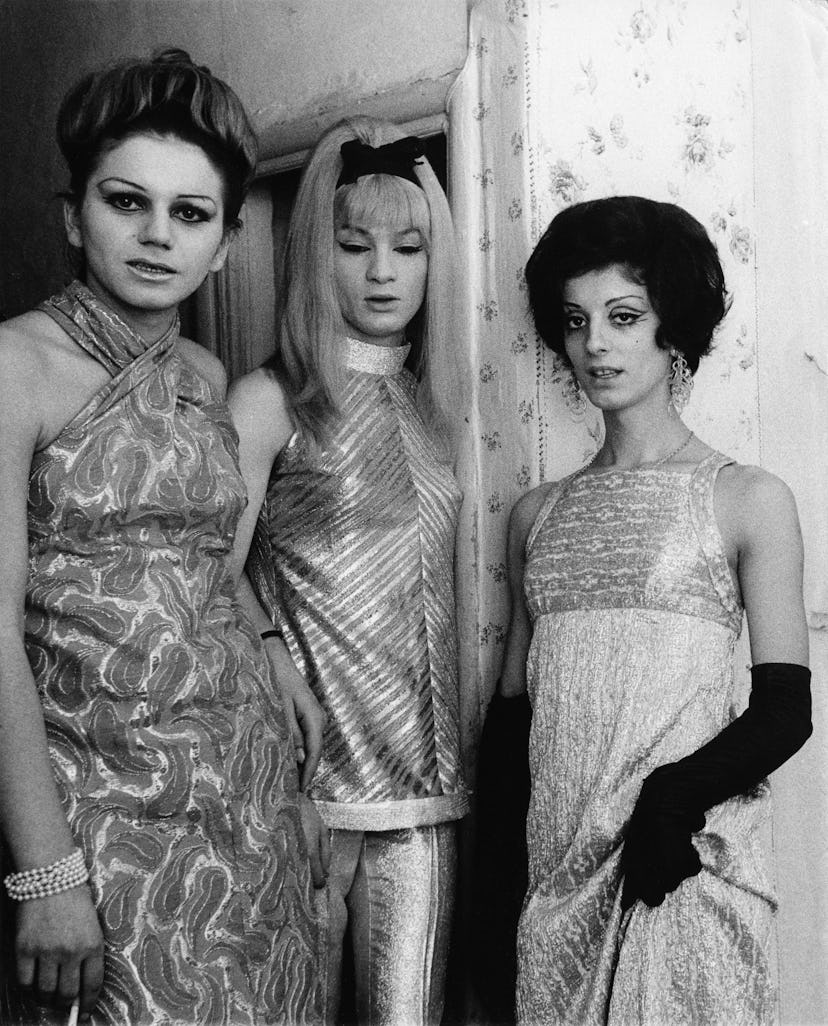

Elisabetta Catalano, Giosetta Fioroni and Talitha Getty, 1966.

Photos: Wannabe Vezzoli?

User submission courtesy of Nowness.

User submission courtesy of Nowness.

User submission courtesy of Nowness.

User submission courtesy of Nowness.

User submission courtesy of Nowness.

User submission courtesy of Nowness.

User submission courtesy of Nowness.

See the women of Sofia Coppola’s “The Beguiled”: