Anne Boleyn has been represented in film and television for nearly a century, dating back as early as a short film from 1912, and as recently as the 2021 film Spencer. Hollywood legends including Vanessa Redgrave, Charlotte Rampling, Helena Bonham Carter, and Natalie Portman, have all played the Queen of England, second wife of Henry VIII, and mother of Queen Elizabeth I. Now, Jodie Turner-Smith, who made a splash in Hollywood when she starred in the 2019 film Queen & Slim opposite Daniel Kaluuya, is the latest actress to take on the iconic role of the betrayed and beheaded queen in the miniseries Anne Boleyn, which drops on AMC+ December 9.

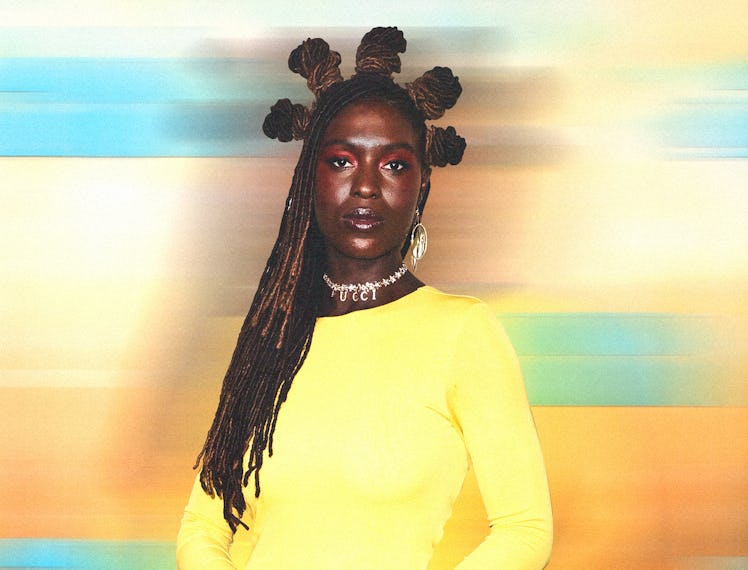

The three-part series focuses on the Queen in the last five months of her life, following the dissolution of her marriage to Henry VIII, the trauma of her miscarriage, her arrest, and imprisonment. In just three episodes, Turner-Smith, who shot the series several months after giving birth to her daughter Janine in April 2020, redefines Anne Boleyn by giving her agency, power, and a distinct personality. Opening with Turner-Smith as Boleyn, dressed in a bright yellow gown and wearing intense gold makeup around her eyes, the series instantly comes alive with the actress’s magnetism. Instead of portraying her as a mistress desperate for power, Turner-Smith depicts her as an intelligent, strategic woman with flaws and feelings.

When she was first cast as the queen consort, Turner-Smith’s casting ruffled some feathers, due to the fact that she is Black and the real royal was white. But in the series, it works—Boleyn stands out amongst a cast of mostly white people, which deepens the viewer’s understanding of her isolating journey. In an interview with W, Turner-Smith opened up about playing Boleyn as a Black woman, and how, from her perspective, the casting decision makes room for more people of color to have similar opportunities to star in period pieces, despite some historical inaccuracies of this one. It “embraces how actors can bring themselves to a character,” Turner-Smith says. The actress also discussed how becoming a mother changed her perspective as an actress, the racial politics of the series, and going public with her own relationship.

Anne Boleyn was the first project you filmed after giving birth. Has being a mom changed your approach to acting?

Definitely. There’s just a different lens I see the world through now, which, I believe, adds some depth and nuance, hopefully, to my work.

Was there anything in particular about playing Anne Boleyn that you might not have been able to tap into if you hadn’t been a mother?

What attracted me to the role was [that] I felt like I really was seeing that element of her story. Not so much what was sensational about her, but the fact that how cool she was as a woman and a mother doing the best that she could to ensure the survival of her children. Having filmed five months after giving birth, I had a connection to this idea of delivering a child stillborn that I wouldn't really have had the scope of reference to in the same way [before giving birth]. As artists, we understand grief, we've all grieved. But this particular horror felt different to me having just been through a live birth, and I wanted to handle that with as much sensitivity and care as possible.

You portray Anne Boleyn in a unique way; the pain she felt after losing a child is rarely placed at the center of her story. But you also portrayed her as a woman who had a lot of power and a lot of pull. How important was that for you to capture?

It was very important for the filmmakers [all three parts were directed by Lynsey Miller]. They really wanted to show that element of Anne, like how she was politically involved and how she wanted to have a say, and even just the religious elements, bringing an English-language Bible [to the royal court]. This idea of her trying to really push forward the conversations around culture and art, how she wanted to use money from monasteries to push England forward in a different way, and how that made her threatening.

There is so much that is already known about Anne Boleyn in relation to Henry VIII, but there is really not much known about what she was like on her own. How did you figure out how you were going to give her such a specific personality?

Eve’s [writer Eve Hedderwick Turner] scripts really told a very beautiful story about what was happening emotionally, internally for Anne. It was really just about bringing the nuances of my own experiences as a human being and as an artist to what was already on the page. I loved how much there were these parallels to modern times. There’s nothing [else] that lets you see how much things have not changed as living and looking into the experience of a woman who lived in the time before this one, and how so many of those limitations still exist.

What does Anne Boleyn mean to you both as a feminist and as a British woman?

I hadn’t really seen her in that feminist light. I felt that she was always portrayed as this seductress, this harlot. It was, did she have sex with her brother? Did she have six toes, six fingers? And it was always a demonization of her. This story was a different one than what I had seen. When I started doing research, I was fascinated by her upbringing and how in many ways she was this outsider, and an adult woman existing in the patriarchy. It made me realize that perhaps so much of her story really is just about how she's been written about by men, and it's not really a true reflection of who she was. And what would I do in some of the circumstances that she was in?

Was there anything in your research on her that you learned that you didn't know about before?

I just didn’t know so much about her upbringing. She basically spent all of her childhood around powerful women and that might have influenced her and why that might have influenced her to be the kind of woman that she was and come to England to make the changes that she did, not purely just trying to be a queen consort.

Anne Boleyn was a predominantly woman-led production. How did that compare to your experiences on other projects?

There are certain nuances to be found when you allow women to be at the helm of telling a woman’s story. [There are] things that are missing when [women are] not in charge of it because of their own internalized prejudices that they’re maybe not even aware of, and some that they are. I think also, as I said, I had just given birth five months before doing this project and there was definitely a different level of compassion and care in terms of the space that I was given to do what I needed to do [as a mother] while also jumping into this role. That was really appealing to me.

I also wanted to talk about the racial politics on the show, which defies convention when it comes to telling a story that’s already been told many times. What’s significant to you about portraying Anne Boleyn as a Black woman?

I think it makes space for and embraces how actors can bring themselves to a character. You know? My individual identity added to the experience of the film. I understand there was a historical figure. Anne Boleyn was a white woman, but as a human being, having a human experience, how much more can we get from the story when we just distill it down to that? When we take race out of the picture and we talk about this idea of experiencing pain, ambition, grief, desire, loss, motherhood, things that are universal experiences? It is wonderful to have the opportunity to just tell stories and to not be limited by race.

I mean this as a compliment, but you’re a very online person, and you’re particularly very sharp, funny, and honest on Twitter. Are there ever days when you just wish that you weren't very online or when you wish you could just put the phone down?

I think it’s good to plug out, so I do. Sometimes I’m not online, I don’t post anything. But obviously our worlds are now in our phones, whether we are actually on the internet posting things ourselves or not. This is how we get our news, our information—it is all in the palm of our hands now. But it’s also good to just get outside and talk to people in real life and be with our family, and I definitely do a healthy amount of putting my phone down and just doing that.

Is there anything specific you do when you unplug?

It’s lots of hot baths. Hot bath, going to a park with my daughter, just talking to my husband.

You and your husband [Joshua Jackson] have become an “it couple” in Hollywood, but you seem to keep a lot of specific details about your relationship private. What is maintaining that balance like for you?

It’s very easy to do that. I’m a millennial. We grew up on the internet, where, in a way, so much of it is normal to have that interaction. But I’m a real human person, and I like to smell trees and swim and hike and read books. There’s so much more of me than what you see online, as with any person, you know? So it's very easy to not give all of myself to the internet because most of my life actually exists outside of it. I don’t have different personalities for different places. I’m not one person on the internet and one person in real life. It’s the same person.

This article was originally published on