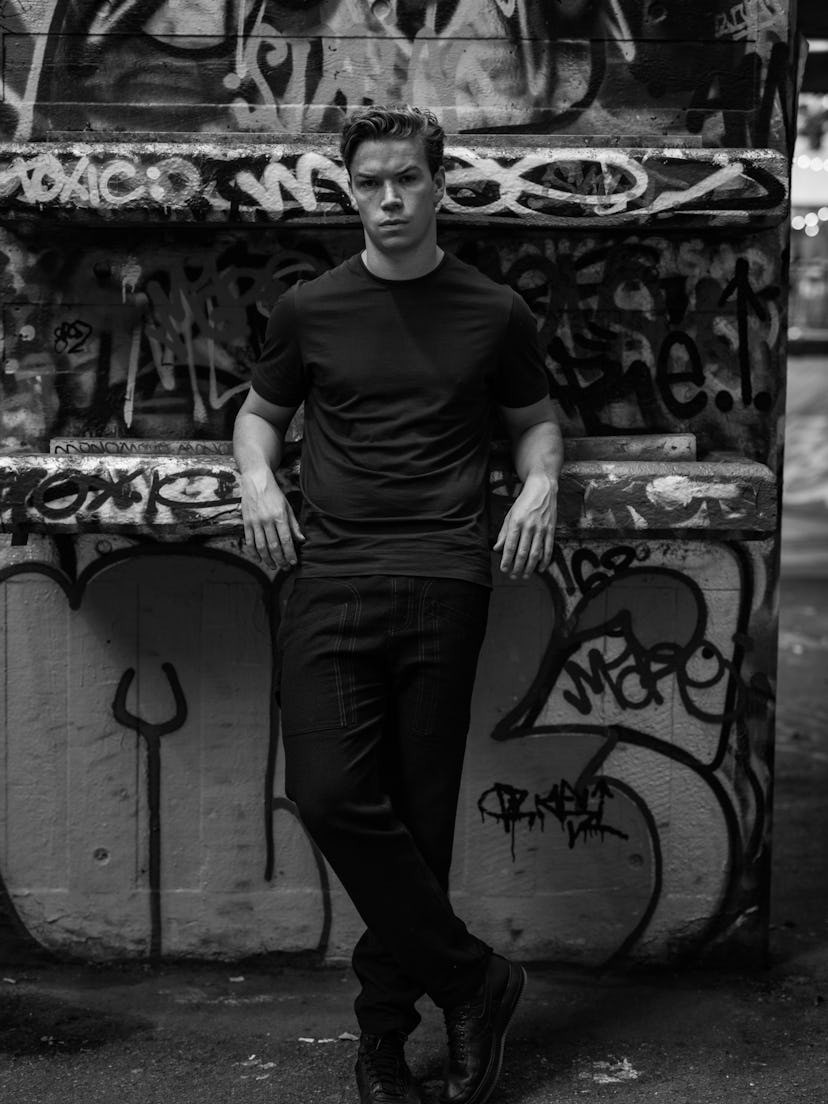

With Dopesick, Will Poulter Finds His Footing in Socially Conscious Roles

In the harrowing story of the United States’ opioid epidemic, which emerged in the 1990s and still exists today, there are plenty of participants, a blend of villains, heroes, victims, and survivors: Purdue Pharma, which created and distributed the drug OxyContin; members of the Sackler family, a powerful clan known for its arts philanthropy and background in changing the face of medicine marketing, which profited billions of dollars from opioids; and the doctors who prescribed the drugs, and, in some cases, became addicted to it themselves. But there is a small group of actors whose roles in the epidemic are often forgotten: sales representatives who worked for Purdue, shopping OxyContin to doctors, clinics, and medical practitioners. Their uniquely devastating story is partly told in the new limited series Dopesick, which debuted on Hulu on October 13. Dopesick, created by actor, director, and writer Danny Strong and starring Michael Keaton, Kaitlyn Dever, Rosario Dawson, and Peter Sarsgaard, gives a birds’ eye view on the entire opioid crisis—telling stories from the perspectives of the opioid addicts, their families, the Sacklers, Purdue executives, the FDA, and the government officials who attempted to take down big pharma.

One of those stories comes in the form of Billy, a Purdue rep played by the British actor Will Poulter. The 28-year-old London native began working in film and television as a child, appearing on sketch comedy shows in England including School of Comedy. Since then, he’s taken on deeply moving, serious roles—appearing alongside Leonardo DiCaprio in The Revenant and starring in Ari Aster’s horror film Midsommar. But as Billy, whom Poulter describes as a “composite character of Purdue reps—not based on any one individual,” the actor says he received an education on the entire opioid epidemic, a topic he “admittedly didn’t know much about.” Through working with Strong, who Poulter says was on set every single day, and reading Beth Macy’s book, Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors and the Drug Company that Addicted America, the actor became fully immersed in the subject. “It was really disturbing to find out just how purpose-built and methodical the effort was from this one company to fraudulently promote this highly dangerous, highly addictive drug as safe and non-addictive,” Poulter says from his home in London, where he’s filming the Agatha Christie adaptation Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? “Then you start to realize, bribery and deception and coercion were pillars of how this company was formed And there always seems to be enough money and enough privilege to escape accountability.”

Below, Poulter discusses the shocking details he unearthed through researching the role of Billy, and why he’s focused on projects that tackle social injustices.

How did the role of Billy come across your desk?

During lockdown, I was slightly twiddling my thumbs. Then I had a meeting with the producer Warren Littlefield, who pitched me this show called Dopesick with a view for me to meet with Danny Strong, the writer and showrunner. I knew Danny’s work from Recount, and Empire, of course. Danny is someone who writes very conscientiously and respectfully of other people’s experiences, so that was important to me. When I heard it was about the opioid epidemic, I was especially interested—I’d actually told my team a couple of years prior that was a subject that I wanted to comment on in some way, if I could, through work, or at least do some work in that space.

I’d gotten tipped off by Warren and by my agent that Danny was a little concerned I might be too young. So, like an idiot, I didn’t shave for, like, three days. I thought the pathetic amount of stubble I could accumulate in 72 hours would make a difference. I put on a white shirt and I tried to act all grown up, hid anything from view that might make me look like the child that I am. Danny offered me the job on the Zoom meeting.

The beard worked.

I’ve got to say, calling it a beard would be a major stretch. But the shadow, or peach fuzz, at most, may have had a subliminal effect.

Tell me about the research you did for this role. Were you able to speak to any former Purdue salespeople who worked on OxyContin?

Unfortunately, no. But between the script and the book, I had two incredibly rich resources; Danny writes almost like a journalist, and Beth didn’t leave a stone uncovered in terms of detailing the epidemic. They both spoke to former Purdue reps—I wasn’t able to. Part of the reason it’s difficult to make contact with former Purdue reps is because so many of them who would have left, shall we say, under less-than-amicable terms, anyone who took a stand, anyone who walked out in protest, were often threatened with legal action. They were paid off to keep quiet. Many of them were intimidated into not taking legal action themselves and not reporting things. And Purdue’s tactics in that regard resembled something more like a mob than a legitimate company; they had unmarked cars waiting outside the homes of former Purdue reps. Former employees were literally stalked in acts of intimidation.

What were some of the most shocking details you learned about being a Purdue salesperson?

Danny had all these incredibly disturbing anecdotes about Purdue reps. If anything, we had to dial the details down for TV. There were milligram dosages being prescribed that Danny was like, I can’t put that in script because people aren’t going to believe it. Or that act of bribery is too ostentatious, so we’ll just have it be flowers going to the receptionist as opposed to offering to pay some of her bills.

In the training program, salespeople were literally encouraged to, based on psychological profiles they were given on each of their doctors, bribe, coerce, and emotionally manipulate doctors into prescribing this entirely dangerous drug. There was one thing that I learned from Beth’s book, a concept called “pitch and pump,” which is where, if you caught a doctor at the end of the day, or on their break, or when they were outside of their practice, you would offer to drive them to the gas station and fill up their car and pitch them while they were having their gas tank filled up. Another concept was called “dinner dash,” which is when reps dropped off groceries and food at a doctor’s practice with samples of pills.

Your character, Billy, sticks around working for Purdue for such a long time, despite exhibiting very real guilt and anger, knowing that he’s playing a role in negatively affecting people’s lives. Why do you think he keeps working for the company, despite the guilt?

Billy represents something that was fairly typical of people who worked there. Initially, he might have come on board assuming that he was genuinely going to contribute to relieving people of their pain. When Purdue presented them with studies that they financed or data that they fabricated, there were no legitimate grounds for them to question it. But I think the reason Billy continued to work for them is that he became embroiled by the culture there, and also the trappings of money and success. With Billy, you see a kid who’s insecure, doubts himself, lacks a certain purpose. And in this company, he’s quickly climbing the ranks, his social skills are making him a big success and allowing him to climb the ladder very quickly. All of that is gratifying and hard to resist as a young 20something-year-old.

The show does put forth a convincing portrayal of a sales bro culture.

There was an anecdote Danny shared with me, from a Purdue rep. Danny asked him, what was the point at which you realized you had to leave this job? And he said, it was when I pulled up at a doctor’s office and thought there had been a mistake. He thought he’d gotten the wrong address because in the parking lot, there was a party with beer kegs and people throwing footballs around. He said it looked like a frat party—but, no, that was the doctor’s office.

Your character works pretty closely alongside Michael Keaton in Dopesick. It’s interesting to me that Keaton worked on another project, Spotlight, which explores the narrative of institutions failing to protect people. I’m wondering if he brought any knowledge from that previous film into this one.

I had a chance to do some press with him recently, and he’s spoken about that: through Spotlight and projects like Worth and Dopesick, he’s grown an appreciation for how the experiences of different human beings lead them to do terrible things. We need to understand how those experiences result in these kinds of actions, which harm other people. We need to understand human psychology as intimately as possible to be able to make sense of these instances of social injustice.

What was it like to work with Michael Stuhlbarg? He’s such a force.

The first time I met Michael Stuhlbarg, he came in an extra hour early to be on the other end of the phone for a scene that he wasn’t even in. There’s a scene where Richard Sackler calls Billy to congratulate him on high numbers. This was one of the first things I ever shot for the show in my character’s apartment. I said to one of the ADs, by the way, is someone going to read for the other side of the telephone conversation? And they said, oh no, Michael’s here. And I opened the bathroom door: Michael was sitting on the edge of the bathtub with a headlamp on, holding the script. It was incredible.

You got your start as a kid in Comedy Lab and School of Comedy, but your subsequent work has spanned so many other genres. How do you think beginning work in comedy has informed your approach to roles going forward?

When I started off, it was like caricature work. And more than anything, at that time, it was just about having fun. I was a kid running through this wild sketch show, putting on different wigs and mustaches and doing two or three characters a day with my best friends. The one thing I’m really grateful for is it gave me a sense of fearlessness, which I don’t always harness, and I struggle to find—because I get really, really nervous and a lot of self doubt, and anxiety. But the lovely thing about that show and that experience with Laura Lawson, who was the creator of School of Comedy, was that she imbued so much confidence in all of us to be able to take on these different characters. She never told us we couldn’t do something, never patronized us, and really threw us in at the deep end. It was encouraging, and helped me build confidence where I don’t think I had much.

How is it possible to switch gears from a goofy, fun-loving genre to more somber roles, even really difficult and evil ones like Detroit, in which you played a racist cop?

Doing Detroit set me on a path to find projects that were especially integrated with social action. I received a reeducation on race and privilege—I say reeducation because so much of what we learn at school is wholly problematic, not particularly accurate, and generally whitewashed and Eurocentric. To get that education I wish I’d always had woke me up to how little I knew, and how much of my privilege I took for granted. The same thing came about with Dopesick. It helped me develop an empathy for the disease that is addiction, and understand the ways in which a capitalist system exacerbates social injustice.

I’m really grateful that, through this process, I get to learn—I’m under no illusions that there are limitations to how much change I can affect as an actor. But I want to shine a light on the real work that’s being done by actual activists and people who work solely in the space of social action, and, where possible, find work that is socially responsible. I won’t forgive myself if I do things that aren’t contributing to society in anything other than a positive way.