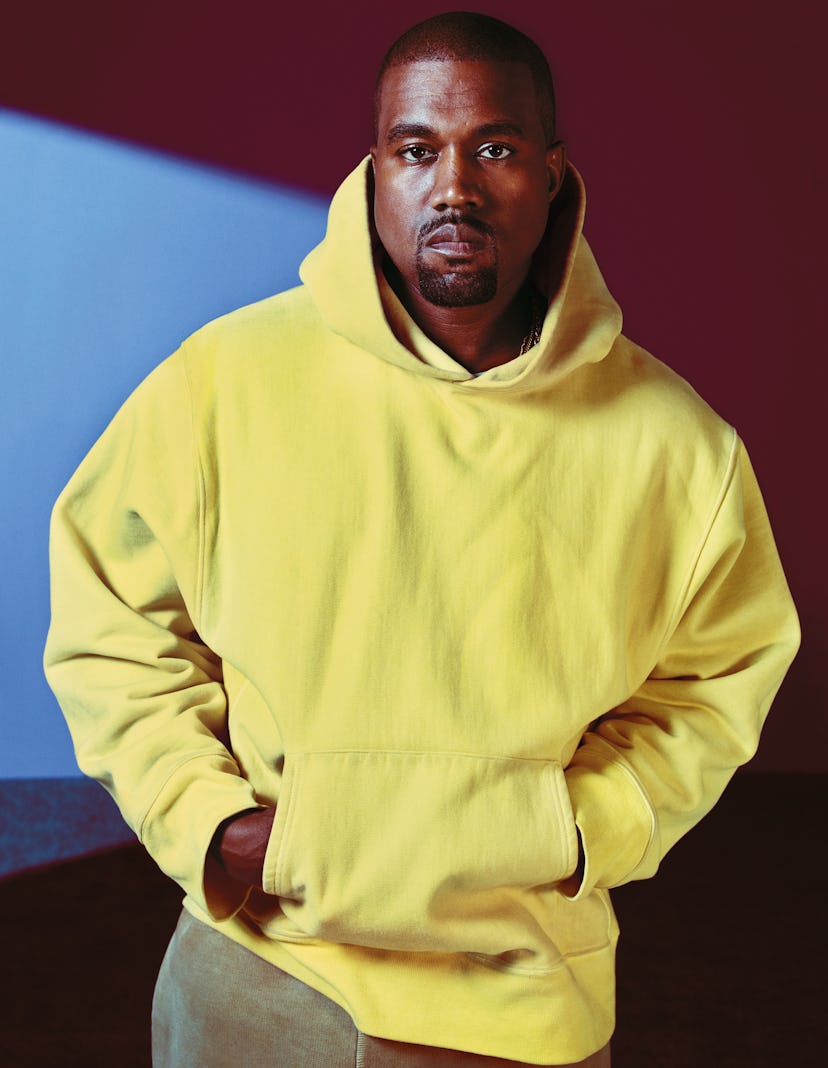

Kanye West’s Weird, Messy, Over the Top Album Releases: A Brief History From College Dropout to YE

The evolution of Ye's rollouts from the backpack rap days to the wild Wyoming adventure.

Kanye West is many things: one of hip hop’s most agile producers; an above-decent and occasionally brilliant rapper; a mediocre fashion designer; and above all a supreme egotist. And he understands how use his self-regard to conjure up a press shitstorm. As his own hype man, West’s self-promotion reaches florid expressions of bombast that—problematic as it has been on occasion (and it really has been lately)—rivals the ecstatic feeling of his music. So while a new Kanye West album—YE, delivered on Thursday night via a livestream (and a listening party in Wyoming)—occasions in the media many deeply considered and surgical taxonomies of those records that preceded it, the public behavior that has accompanied each should also not go unexamined. Since his major label debut in 2004, West’s promotional efforts have evolved—not always for the better, but they have always crashed into the current moment head-on.

The College Dropout-slash-Get Well Soon mixtape

Although West had been producing tracks for artists like Lil’ Kim and Dead Prez as far back as 2000 (earlier if you count Jermaine Dupri, but we don’t have to), he was widely unknown until 2002, when two weeks after falling asleep at the wheel and shattering his face in a head-on collision, West recorded “Through the Wire” with his jaw still wired shut. “Through the Wire” was initially released on the mixtape Get Well Soon that December, and then as the lead single from his Roc-A-Fella debut the following September, proceeding to creep up the Billboard Hot 100 to number 15, where it stayed before the album’s official release date (which, it should be noted, as a taste of things to come, was postponed at least three times). But because he was still largely unknown, West in the College Dropout era was better known for a look than he was for making public his inner monologue. And, propelled by a certain novelty that diverged dramatically from gangsta rap revivalists like 50 Cent who were prevalent at the time, the aesthetic was dubbed “backpack rap,” after West’s penchant for carrying his demos in a Louis Vuitton backpack, and wearing Polo Bear intarsia sweaters, and sherbert-tone polos.

Late Registration

The lead-up to West’s sophomore effort had a shorter tarmac. It feels quaint now, but album hype circa 2005 consisted of radio plays and music video premieres on TRL, an ancient youth ritual where teenagers would assemble in Times Square and pray to the false god of Nick Lachey. “Diamonds From Sierra Leone” debuted on New York’s Hot 97 on April 20, 2005, and was followed two months later by a video directed by Hype Williams. The second single, “Gold Digger,” a massive earworm that gave white kids in freshman English permission to contort themselves around bouncy racial epithets, arrived on July 5, and became West’s first Billboard Hot 100 number one, as well as the fastest selling digital single of all time in the early stages of iTunes, a defunct technology fueled by gift cards from your aunt.

Thematic continuity was not a new idea for rappers (see Jay-Z’s The Blueprint, The Blueprint 2, The Blueprint 2.1), but West’s higher education framing device felt different, ferried by the mascot Dropout Bear, a dejected looking teddy bear that dressed like he owned a copy of the Japanese American collegiate bible “Take Ivy” and spent his free time on menswear message boards. West made an in-store appearance at New York’s Lincoln Center Tower Records (rest in power). That same day, Late Registration was released for online streaming on AOL Music (Jesus Christ).

Graduation

The culmination to West’s student life suite, the rollout to Graduation incorporated a visual identity that plunged Dropout Bear into the superflat artwork of Takakashi Murakami, a deft pairing that conjured West’s themes of psychological dislocation inside Murakami’s sunnily sinister language.

On May 11, 2007, West announced a September 18 release date for the album while debuting its first single, “Can’t Tell Me Nothing,” on Hot 97. Def Jam pushed up the album’s release a week to September 11, the same day that 50 Cent’s third studio album, Curtis, was scheduled to release, envisioning a devastating nouveau rap beef but prompting instead a vague two-month tension that’s hard to believe we allowed. A fun exercise would be to walk outside today and interrupt a teen adding content to his YouTube channel and ask, “What would think if I told you there was a time not too long ago when the record industry tried to manufacture a Kanye West-50 Cent beef” and see how long it takes him to call the police.

The scheme was doomed from the start, as rap beefs, by definition, require two participants of similar standing, or at their basest level, two participants. On August 10, 50 Cent promised that he would end his career as a solo recording artist if Graduation were to sell more copies than Curtis in the United States, a stunningly prescient vision 50 was nonetheless forced to retract due to his contract agreements, but of course, like The Secret, he put it out there, and that’s pretty much what happened!

808’s & Heartbreak

Prompted by the psychically catastrophic death of his mother and the dissolution of an engagement, and feeling penned in by the limits of genre-based expectation, West began production on 808’s, an album of avant electro-chamber music-as-catharsis. He debuted “Love Lockdown” on September 7, 2008, as the closing number at the 2008 MTV Video Music Awards, subsequently releasing it as a free download on his blog. On October 16, he released an excerpt of “Coldest Winter” on Power 106 in Los Angeles, after which most of the rest of the album found (leaked) its way online.

By way of signaling his maturation, or tonal shift, or something, West jettisoned the sherbert polos for a new aesthetic, via a portrait by Willy Vanderperre, of a grey glen plaid suit, large browline glasses, a heart-shaped pin, and a melancholy affect.

West contacted the Italian conceptual artist Vanessa Beecroft to conceive a promotional listening event. She delivered a Kubrickian tableaux of 40 nude women wearing wool masks who stood silently in the center of the room, illuminated by multicolored lights that alternated in sync with the music, something she says she conceptualized and generated in a week, which is clear.

My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy

Following his breathtakingly heroic intervention at the final culturally relevant MTV Video Music Awards in 2009, West was grappling with a public image crisis, namely that his public image was one of noxious, weaponized ego. He cancelled his double-bill tour with Lady Gaga in support of 808’s and, as any of us would in a period of great personal strife, repaired first to Milan, and then Oahu. There, in opulent exile, West began production on his new album.

By February of 2010, information about the album, which bounced around corners of the internet as Good Ass Job, was reaching the mainland in drips and various degrees of veracity (this was also a time West was bringing up Big Sean, the Chipotle of hip hop, who Tweeted a lot of nonsense).

On July 28, 2010, West announced via his new Twitter account that “The album is no longer called ‘Good Ass Job’ I’m bouncing a couple of titles around now.” In August, West began releasing free songs through his GOOD Fridays series, both a goodwill tour and heretofore unprecedented marketing salvo, introducing the singles “Power,” “Monster,” “Runaway,” and “All of the Lights,” which contains the inspired bar “Public visitation / We met at Borders.” On September 12, West returned to the MTV Video Music Awards to tease the short film Runaway, a dream state redemption play scored to the record’s music, with a screenplay by Hype Williams and art direction by Beecroft and “creative consultation” by West consigliere Virgil Abloh.

Much of the runup to MBDTF circulated around its cover art, a series of paintings done by the artist George Condo in his Artificial Realism style which seemed to render West’s very id—a berserk Dropout Bear, a manic head screaming from four mouths, and a calmer version, crowned and decapitated and with a sword plunged through it (which West has used as his Twitter avatar since). In successive Tweets on October 17 (“Yoooo they banned my album cover!!!!! Ima tweet it in a few…” followed by “Banned in the USA!!! They don’t want me chilling on the couch with my phoenix!”) West intimated that his preferred art, a depiction of him being mounted by a zaftig, armless, and nude winged creature, had been censored. By who, exactly, was never really clear. On November 22, the album debuted at number one on the Billboard 200 and eventually sold 1.3 million copies in the United States.

Yeezus

After completing the collaborative Jay-Z vehicle “Watch the Throne” the following year, West began dating Kim Kardashian in spring 2012. By December they were pregnant, and by January they had closed on an $11 million Bel Air mansion. On May 1, 2013, Kanye Tweeted the words “June Eighteen,” a cryptic transmission that led several Kanyeologists, through Ouija boards and star cycles, to speculate that West would be releasing an album on the eighteenth day of the sixth month. Their controversial theories were vindicated 16 days later, when “New Slaves” was projected on Wrigley Field in Chicago and the Prada Store on Fifth Avenue in New York, along with 64 other building facades worldwide.

The next day, West performed that track, along with “Black Skinhead” on Saturday Night Live, and announced the album’s cover and title, Yeezus, on his official website. Eschewing high-profile collaborators like Condo and then-Givenchy designer Riccardo Tisci, who had created the baroque, gilded cover art for Watch the Throne, West instead bit a 2001 New Order cover, presenting a clear CD jewel case affixed with a piece of red tape.

The Yeezus cycle is notable as it marks the beginning of the KimYe epoch, in which the full weight of the Kardashian machine was harnessed in selling West’s vision to the world. On May 18, 2013, Kardashian posted an image of the Yeezus jewel case artfully laid alongside a single Yeezy Red October shoe, with the gnomic caption “#Yeezus #RedYeezy’s #SNL#Tonight #NewSlaves #YeezySeason#Donda #June18.” On June 17, Bret Easton Ellis tweeted, “Scott Disick’s Dream Comes True in the promo that I originally wrote for Kanye’s new record but not a lot was used,” referencing a parody of American Psycho in which Disick portrays Patrick Bateman to “Food God” Jonathan Cheban’s Jared Leto. Probably for the best, Bret.

The Life of Pablo

Where once West was content to let the work speak for it self, promoting it within the more or less predictable confines of the record industry handbook, by 2010 West’s public persona had become erratic and exhausting, subjecting the public to a year-long odyssey of manic pronouncements. (What’s that crippling self-doubt, Margiela?)

After teasing a new album toward the end of 2014, Kanye released the back-to-back singles, “Only One” and “FourFiveSeconds” in January 2015. The next month, West realized his goal of disseminating muted basics on a mass scale with his Yeezy brand, an Adidas partnership that debuted at New York Fashion Week. West announced the first of a cavalcade of tossed off album titles, So Help Me God, in a tweet on March 1, changing it to SWISH two months later before… mostly disappearing until January the following year, when he released “Real Friends” and “No More Parties in LA,” and declared that the album would be out February 11.

By the end of January, West had Tweeted a handwritten tracklist, along with a mock Rolling Stones cover photographed by Tyler, The Creator, and entered into a Twitter spat with Wiz Khalifa, which gave us the gem “You have distracted from my creative process” and the phrase “cool pants” as a devastating personal indictment. A few days later, SWISH had become Waves. A month after that, he tweeted “T.L.O.P.,” sending amatuer Kanyeistesiologists into violent roils and effectively halting all foreign trade.

On February 11, the scheduled release date for the album he had or had not yet named, because who among us could say they truly knew? West hosted 200 of his closest friends at a joint listening event and presentation of his Yeezy Season 3 at Madison Square Garden, in which West played the album from his personal Macbook via an aux cord amidst a Beecroft set piece based on Paul Lowe’s 1995 photograph taken during the Rwandan genocide, before playing a trailer for a video game he created about his mother entering the gates of heaven; leading the Garden in a “F— Nike” chant; thanking Carine Roitfeld for “being a real b—-;” and telling us that one of his dreams is to become the creative director of Hermès.

Usually this is where a publicity cycle more or less enters the touring stage, except West continued to make changes to The Life of Pablo, describing it as “a living, breathing, changing, creative expression,” citing the end of the album as a dominant release form (basically true), comparing himself to Saint Paul (possibly true?), and trying his hand at unfair business practices, declaring that he would never release the album outside of Tidal, encouraging his fans to sign up for the service (not successful). After this really busy weekend, he announced that he was $53 million in personal debt and appealed to Mark Zuckerberg, who “loves hip hop” to invest $1 billion in West’s ideas. Not to be ungracious, he also tweeted “hey Larry Page I’m down for your help too.”

YE

No one knows what goes on inside the mind of another person, not his family, not his artistic collaborators or assorted hangers-on, not the unslakable maw of the internet. Speculating about it publicly is tacky at best, but we’re going to do it anyway. It’s probably likely that in the intervening years since TLOP that West has dealt with bouts of manic depression, manifesting itself in unfortunate public appearances at Trump Tower in August 2017, and most recently, a days-long and increasingly looney Twitter spree which co-opted the public attention. West, apparently realizing he has too much money to not be a Republican, proclaimed his love for Trump, called him a brother and acknowledged their shared dragon energy.

None of this was presumably in promotion of any music project, until it was, and West announced a spray of forthcoming projects, including the already-released hydra of Pusha T’s Daytona; a collaborative effort with Push’s How To Make it in America co-star Kid Cudi; and Nas’s upcoming eleventh album. Published chains of rambling text messages and prospective cover art incorporating images of the plastic surgeon that performed the procedures on West’s mother, leading up to her death, followed; followed still by speculations and recriminations, snide public defenses by Kardashian, and a public contretemps with West’s erstwhile associate Rhymefest, in which he accused West of abandoning the struggling Chicago-based youth charity they started together and named for West’s mother, to which Kardashian responded by accusing him of owning bootleg Yeezys.

Oh, and on Thursday, he flew planefuls of people to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where he’s secluded himself, for a listening party amid the mountains, which he then livestreamed on the WAV app, which is maybe the AOL Music of 2018? The last few months for West have been ugly, though perhaps not much uglier than what’s happening in the rest of the country. Lately, an uglier tomorrow always seems possible. Daytona has already reignited Push’s hoary feud with Drake, which was thrust into new, gruesome levels. To a large degree, and for a long time, West’s work, sonically and socially, has presaged where we go next. If this is indeed a surgical summer, let’s hope our insurance covers it.